Iran Says Taliban Responsible For Security During 'Temporary' Government

At the opening of a conference on Afghanistan in Tehran, Iran’s foreign minister said that the Taliban are responsible for ensuring security for all citizens.

At the opening of a conference on Afghanistan in Tehran, Iran’s foreign minister said that the Taliban are responsible for ensuring security for all citizens.

Hossein Amir-Abdollahian in his opening speech at a meeting of Afghanistan’s neighboring countries and Russia said, “We must emphasize that the responsibility of security for Afghan citizens, as well as security at the borders of this country with its neighbors, first of all lies with the ruling council temporarily in charge of Afghanistan.”

Amir-Abdollahian’s use of the word ‘temporary’ refers to Iran’s position that the Taliban must form an inclusive government in the multi-ethnic, multi-sectarian country.

Iran has also called on the Taliban to provide security after attacks in recent weeks against Afghanistan’s Shiite community, at the same time claiming that the United States is fomenting violence through extremist groups.

The Iranian foreign minister also called on the international community “to pay special attention” to political and humanitarian problems, as well as to terrorism, narcotics trafficking and women’s rights in Afghanistan.

The Iranian foreign ministry had called on the Taliban on Tuesday, ahead of the Tehran conference, to form an inclusive government and prevent violence.

Iran had cautiously welcomed the Taliban takeover in August, saying it was a strategic defeat for the United States.

Ali Yazdikhah, an Iranian lawmaker, says it will take another 3-4 months before President Ebrahim Raisi's economic team can begin to implement its policies.

After criticism of government inaction echoed in media in recent days, the conservative lawmaker defending the administration said it needs time to coordinate efforts among officials and agencies. He even went further, suggesting that it is only after that period when ministers will have to be accountable to Majles (parliament).

Yazdikhah made the comment in an interview with Khabar Online website on Tuesday, while the Raisi administration has already been in place for nearly three months without any sign of trying to meet its promises, including building one million homes in 12 months, and addressing the dire economic situation people face.

However, Yazdikhah said he was sure the administration can stand by those promises despite a 50-percent budget deficit, without explaining how that would be possible. However, he acknowledged that it is highly unlikely the government could build even 400,000 houses in one year.

Asked about what the Majles has been doing, Yazdikhah claimed that the lawmakers at the parliament have been working hard, but the media failed to reflect their hard work. However, he agreed with Khabar Online that the parliament has done very little to follow up on the promises made by the Raisi administration to tackle the ongoing economic crises.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday reformist daily Aftab Yazd in an article reviewed some of the impractical suggestions made by cabinet ministers to solve the country's ongoing problems. The daily characterized some of the comments made by Raisi's ministers as "noise pollution at Pasteur Avenue," where Iran's cabinet office is located in Tehran.

Aftab Yazd advised that the administration needs a media adviser to brief the ministers on the impact of their misplaced or outlandish comments and to prevent embarrassments. As an example, the Cultural Heritage Minister suggested last week to dig water wells next to Cyrus the Great’s 2,500-year-old tomb revered by the nation. The minister later tried to walk his comment back, but the damage was done. The daily added that denying such comments is always less effective than the initial comment or action that leads to the erosion of people’s trust in the government.

As an example of lofty statements by top officials, the daily referred to remarks by Industry Minister Reza Fatemi Amin who said recently: "We will manufacture so many cars next year that the people will not have to wait in line." The minister also promised a gradual reduction in car prices. This, the daily said, was like the promises made earlier this year to produce so many Covid-19 vaccines to saturate the markets in Iran and to export the surplus. Those who made this promise, admitted later that all their planning was wrong, the paper said.

Mr. Amin also promised to put an end to the Iranian economy's need for the US dollar. The daily said the claim could have only been made by an official in a country whose national currency was not critically devalued. Iran’s currency has lost its value ninefold since 2017.

Aftab Yazd also highlighted another comment by Khandouzi about the need to finish incomplete projects and said: "Please finish these incomplete projects before starting new ones," and stressed that "the economy minister certainly knows that finishing the incomplete projects takes at least 12 years and needs a budget in excess of hundreds of trillion of rials."

Last but not least, was a comment by Central bank Ali Salehabadi who has said, "Iran has left behind the recession." Referring to multiple serios economic challenges and calls to hasten the process of taking a loan from the International Monetary Fund, Aftab Yazd asked "How exactly did you leave the recession behind?"

Enrique Mora, the EU envoy coordinating the Iran nuclear talks traveled to Tehran recently in an attempt to convince the regime to return to the Vienna process.

The EU invested considerable political and diplomatic capital in the long process that led to the 2015 accord, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). EU leaders had tried hard to convince former President Donald Trump not to abrogate the deal, and they have again invested considerable effort, since Joe Biden’s election, to serve as a middleman between Tehran and Washington. All of this diplomacy invites an economic question: What can the EU expect to gain if trade and investment become possible in Iran with the lifting of US sanctions?

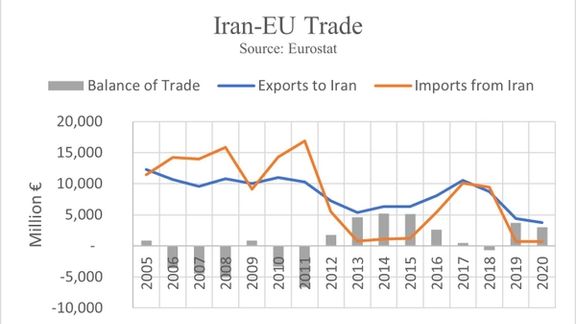

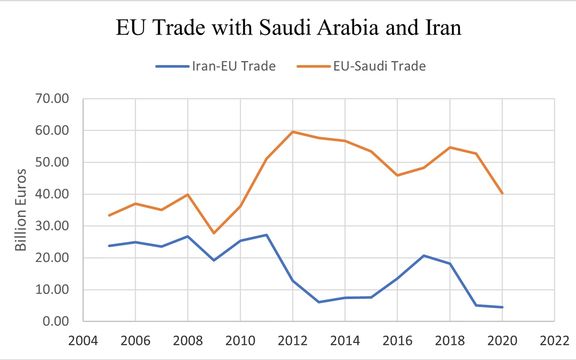

The history of Iran-EU trade over the last 15 years shows a downward trend, with a high degree of correlation with the severity of sanctions. When US-initiated secondary sanctions are in place, whether multilateral or unilateral, they quickly affect Iran-EU trade. EU states opposed the Trump administration’s unilateral maximum pressure strategy, but Trump’s sanctions had the same impact on Iran-EU trade as multilateral sanctions did prior to the JCPOA.

In no small part, Iran-EU trade is so sensitive to sancitons because the EU can quickly replace Iran with other trade partners, while Iran can not do likewise. In 2013, at the height of the Obama administration’s sanctions campaign against Iran, EU imports from Iran dropped to 751 million euros from their zenith of 17 billion euros in 2011.

In 2019, the first full year that Trump’s maximum pressure strategy was in place, EU imports from Iran slid to 680 million euros, down from 9 billion euros in 2018. EU exports, while reduced due to US sanctions, have shown less volatility. The EU’s 2013 exports plummeted to 5.3 billion euros from their high of 11 billion euros in 2010. These exports went back up to 11 billion euros in 2017 while the JCPOA was in effect, but in 2020 descended to 3.7 billion euros. Non-Iranian trade partners filled the gaps.

By contrast, trade between the EU and Saudi Arabia, Tehran’s chief rival in the Persian Gulf, benefits from diplomatic stability. Since 2005, EU-Saudi trade has enjoyed a general upward trajectory, even though it is sensitive to volatile markets for oil. However, the Saudis have managed to expand their non-crude exports to the EU. In 2020, 7.2 billion euros — 46 percent of Riyadh’s exports to the EU — were from non-crude oil, up from 3.84 billion euro in 2005.

The greater volatility of EU imports from Iran stems from the impact of sanctions on the import of crude oil. Iran’s non-crude exports to the EU are neither considerable nor growing. They still have not returned to their 2007 level of 1.7 billion euros, and in 2020 were slightly above 600 million euros.

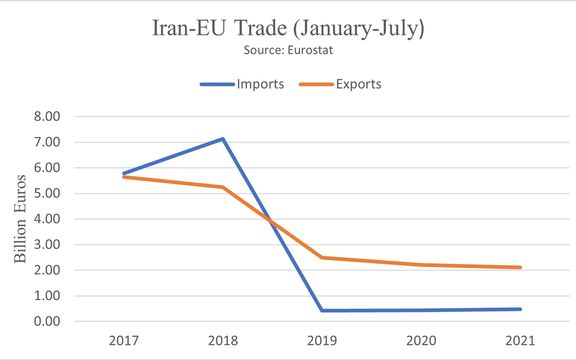

European governments opposed Trump’s unilateral sanctions and tried to convince European companies to trade with Iran. However, the private sector defied Brussels and complied with Washington’s sanctions. Despite loose enforcement of US sanctions by the Biden administration, the data for the first seven months of 2021 show no significant increase in trade between the EU countries and Iran. During this time period, EU’s imports from Iran rose to 480 million euros, slightly higher than 440 million euros during the same period last year, while its exports dropped from 2.21 billion euros to 2.11 billion.

The future of negotiations between Iran and the United States is not promising. The regime is stalling negotiations in order to expand its nuclear program with impunity. Tehran may even develop a nuclear weapon while Biden is in the White House. If Iran goes nuclear, trade with the EU will likely take a dive nearly to zero. It is not clear how much longer Iran can engage in bad-faith negotiations without triggering a meaningful reaction by the Europeans. In the absence of some kind of deal, Iran-EU trade will gradually shrink more. Iran could lose its European market for a long period of time — if not permanently — and the same can happen to European exports to Iran.

Despite its hesitation to rejoing the JCPOA, Iran may decide to accepta “less-for-less” agreement, whereby Tehran would make limited concessions on its nuclear program in exchange for limited U.S. sanctions relief. In so doing, Tehran can keep its nuclear options open until after the 2024 presidential elections in the United States. However, if such a deal resembles the November 2013 interim agreement that preceded the JCPOA, formally known as the Joint Plan of Action (JPOA), Iran-EU trade will improve slightly but is unlikely to rebound fully. The key beneficiaries of a “less-for-less” deal would be Chinese companies, whose currently illicit trade with Iran could come out of the shadows.

After the JCPOA’s implementation, Europe’s imports of Iranian oil — in terms of volume, not value — went back to their pre-2012 level by 2017, even though their value was smaller due to lower oil prices. That quick reversal, however, may not be on the menu this time, at least before 2024, because of the increased political risk of doing business with Iran. If the JCPOA is revived, a complete restoration of oil trade between the EU and Iran could develop, but would still face obstacles.

First, there is a real risk of a Republican comeback in 2024. As Trump demonstrated, the prospect of a Republican president tearing apart a deal made by a Democratic predecessor is real. If a Republican administration decides to revive the maximum pressure campaign in 2025, the process of leaving the JCPOA will probably happen much faster, since the year-and-a-half political debate that preceded Trump’s withdrawal in 2018 is unlikely to reoccur. Consequently, large multinational firms may decide to take their time to reenter Iran, especially if Tehran and Washington reach a deal close to the U.S. presidential election.

Second, the government in charge of Iran is not led by the so-called moderate Hassan Rouhani. The current president, Ebrahim Raisi, the butcher of Tehran, is a mass murderer in bed with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) — the regime’s praetorians — and the most radical elements of the Islamist establishment. This reality increase the political risk of doing business with Tehran.

Third, the regime in Tehran may have its own reservations about resuming trade with the EU. Recently, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic, banned imports of South Korean home appliances — likely as retribution against Seoul for its compliance with U.S. sanctions. Furthermore, over the last decade, European companies left Iran in limbo and failed to adhere to their financial commitments, not once but twice, under U.S. pressure — first in the 2011-2013 sanctions period and then after the maximum pressure in late 2018. The resulting tension between the EU and Iran suggests that even if Iran returns to the nuclear deal, it may not welcome European exporters. Instead, Tehran may decide to prioritize working with Chinese companies or outright ban imports of European goods in specific industries.

The fate of the JCPOA and Tehran’s nuclear program is not clear. As time passes, however, optimism about the resurrection of trade between Iran and EU may become less and less warranted.

The opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily the views of Iran International

Iran's state media have said that a cyberattack caused massive disruption at gas stations across the country on Tuesday, as special smart cards stopped working.

With speculation rampant on social media, Nour News, a website close to the Supreme National Security Council, denied any ploy by the government to soften up public opinion for a gasoline price increase. But almost immediately social media was full of rumors that the government was testing to see public reaction to a possible price increase. Drivers rushed to gas stations to fill their tanks, even if they did not any fuel.

Videos posted on social media Tuesday showed long queues in front of petrol stations. Distribution of cheaper, rationed petrol, which depends on the use of smart cards, had been stopped, with motorists obliged to buy unrationed gasoline at twice the price. By afternoon, authorities said they were working to resume rationed sales at designated stations.

Simultaneously, some electronic road signs were hacked to show messages like "Khamenei, Where is our gasoline?", a question addressed to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in Esfahan.

Another sign announced "free gasoline at Jamaran service station," referring to where the leader of the 1979 Islamic Revolution Ruhollah Khomeini lived before his death in 1989. During the 1979 revolution Khomeini was promising Iranians free electricity, water and a cash share of the oil export income.

The developments echoed July’s disruption to Iran’s railways, when information boards in train stations announced “Long delays due to cyberattack” and advertised the telephone number of Khamenei’s office. Similar attacks hit Mashhad and Tabriz airports in 2018.

But the disruption also comes as Iran enters the month of Aban, the anniversary of the mass protests of November 2019, when hundreds were killed, thousands arrested and the Internet largely shut down for a week.

No group claimed responsibility for the disruption to gas stations. Mehdi Mahdavi-Azad, a political commentator, told Iran International it was too early to say if this was an Israeli attack, but noted that both last November’s killing of nuclear scientist Mohsen Fahkrizadeh and April’s attack on the Natanz nuclear site, both widely attributed to Israel, had “serious repercussions” for Iran’s security services.

“Now even Mohsen Rezaei (former Revolutionary Guard commander) says there is a massive ‘bug’ and enemy infiltration in Iran’s security forces,” Mahdavi-Azad said.

Fars news agency, affiliated to the IRGC, attributed Tuesday’s gas-station disruption to "anti-revolutionaries" and opposition media.

The Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA), the first Iranian media outlet to report the attack Tuesday morning, published a picture showing the telephone number of Khamenei's office on a service station monitor. But the agency removed the report from all its portals and social media after a few minutes, claimed that it had itself been hacked.

A foreign policy advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader has said that Taliban will receive support if they form an inclusive government and prevent foreign influence in Afghanistan.

Kamal Kharrazi, head of Iran’s Strategic Council on Foreign Relations said on Tuesday that “If Taliban, during their rule provide for the formation of an inclusive government of different minorities, protect the country’s independence and not allow foreign powers to have a presence and influence in the country, they will be embraced by the Islamic resistance front.”

The Islamic resistance front is a reference to an anti-American regional group of forces maintained by the Islamic Republic, including Iraqi Shiite militias, the Lebanese Hezbollah and Yemen’s Houthis.

Kharrazi in fact appears to be asking the Taliban to join Iran's alliance system in the Middle East, while the new rulers of Afghanistan are closely aligned with Pakistan where they were sheltered for two decades.

Khamenei’s advisor, however, added that “It is too soon to speak about the Taliban movement.” He went on the say that Iran cannot forget the killing of its diplomats in Mazar-e-Sharif in 1998, while both Taliban and Pakistan had assured Tehran about their safety.

Kharrazai’s statement came one day before a meeting of Afghanistan’s neighbors is due to take place in Tehran.

The UN Special Rapporteur for Iran said in a report on Monday that Iran often uses lethal force against protesters exercising their right to peaceful assembly.

Javaid Rehman, who has not been allowed to visit the country, pointed to live ammunition used during water protests in the south-western province of Khuzestan in July, when he said at least nine people including a minor were killed and others injured.

Many international human rights organizations, experts, the media and some governments have accused Iran of killing hundreds of protesters since late 2017, using military ammunition.

Zahra Ershadi, Iran’s deputy ambassador to the UN, said that such reports "only aim to use human rights as an instrument against other countries" and that Rehman had used information provided by "terrorist groups" and "sworn enemies of the Islamic Republic."

Ershradi said the appointment of a special rapporteur for Iran – since the 1980s one of few countries to be so investigated – had been an initiative of the West, especially Canada. Reflecting Iran’s common approach of alleging double standards, Eshradi cited recent discoveries in Canada of mass graves of indigenous childrenforced to attend residential schools.

Kazem Gharibabadi, Secretary-General of Iran’s Human Rights Office, said Rehman’s report was “ill-intentioned” and "a completely political and diversionary measure."

The Special Rapporteur’s report said Iran’s use of torture, reliance by courts on confessions, and “other fair trial violations” had led him to conclude that the use of the death penalty amounted to “arbitrary deprivation of life." Rehman cited Kurdish prisoner Amir-Hossein Hatami, who died after allegedly being beaten by prison officials, and the death of Shahin Naseri in custody in September. Naseri was a witness in the case of former cell-mate Navid Afkari, executed last year after alleging he had confessed under duress to murdering a security guard during protests.

“Arbitrary” grounds for a death sentence could turn the punishment into "a political tool,” Rahman argued. While a large number of executions in Iran are carried out for drug offences, Rehman criticized three vague security charges that can carry the death penalty: moharebeh (“waging war against God”), efsad-e fel-arz (“corruption on earth”) and baghy (“armed rebellion”).

The UN Special Rapporteur said he was disturbed by the sentencing of juveniles (under 18s) to death and said it was “imperative” for Iran to undertake criminal law and justice reforms beginning “most urgently” with a moratorium on the death penalty for juvenile offenders.

Rehman was appointed in 2018 as the third Special Rapporteur for Iran since the re-establishment of the mandate in 2011 after a nine-year interval. His mandate was extended by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR) on March 24.

The first Special Rapporteur on Iran, Venezuelan Andrés Aguilar, lasted two years after he was appointed in 1984, resigning over Tehran’s refusal to cooperate. Reynaldo Galindo Pohl El Salvador, who took over, visited Iran three times between 1990 and 1992 but resigned in 1995 when barred from returning. He was succeeded by Maurice Copithorne, a Canadian lawyer, who was Special Rapporteur until 2002.