Rights Defenders In Iran Received A Total Of 479 Years In Jail In 2021

An Iranian human rights group says rights defenders in Iran in 2021 received a total of 479 years in prison and were subjected to a host of inhumane treatments.

An Iranian human rights group says rights defenders in Iran in 2021 received a total of 479 years in prison and were subjected to a host of inhumane treatments.

Human Rights in Iran, based in New York, in a report issued on December 16, titled ‘100 Iran Human Rights Defenders 2021’, has provided updates on the status of 100 human and civil rights defenders who are either in prison, released on bail or were subjected to harassment by authorities. Those who were convicted this year received a total of 479 years in prison and 907 lashes.

In every case, the accused were tried without due process of law, being either denied a lawyer or forced to accept government-approved attorneys, without full access to case material.

Iran Human Rights Director, Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam said: “The world must not be a silent witness to the high price Iranian human rights defenders are paying for fundamental rights.”

Human rights defenders, activists and families of victims who received sentences or were subjected to harassment and intimidation doubled in 2021, the report says. The 100 people profiled in the report are “lawyers, journalists, teachers, women’s, workers and civil rights activists, environmentalists, minorities and whistleblowers.”

Iran slammed a critical human rights resolution passed by United Nations General Assembly Thursday, accusing Canada and the United States worse of violations.

Speaking to reporters, Kazem Gharibabadi, secretary of Iran's High Council for Human Rights, said the resolution was "full of baseless claims" while human rights were extensively violated in Western countries.

He cited Canada, the countrythat drafted the resolution, which was co-sponsored by Israel and the United States. The discovery of mass unmarked graves of 1,200 indigenous children in Canada has highlighted the state’s forced separation from parents of 150,000 children from mid-19th century to 1980.

The resolution adopted by UNGA Thursday, 78-31 with 69 abstentions, expressed serious concern at the "alarmingly frequent" use of the death penalty, including against juvenile offenders, torture, and arbitrary arrests in Iran.

It highlighted "torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment," which it said might include sexual violence as well as serious restrictions of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, and arbitrary arrests.

Gharibabadi, who is also the judiciary’s international relations deputy, said Iran's laws on torture were stricter than the UN Convention Against Torture. Iran is not a signatory to the UN convention, although Canada is.

Gharibabadi said that the Iranian legal system offered the chance of redress. "We have said repeatedly, anyone who claims to have been tortured should take their case to the authorities designated by the judiciary and the High Council for Human Rights and we will seriously follow it up," he said.

Although Iran often cites violations in Western countries as an indirect way to defend itself,

The resolution adopted by UNGA Thursday expressed serious concern at the "alarmingly frequent" use of the death penalty, including against juvenile offenders, torture, and arbitrary arrests in Iran. Human rights organizations and United Nations experts have called on Iran to end executions, especially those of juvenile offenders such as Arman Abdolali who was executed November 24 murdering his girlfriend when he was under 18. Iran has had the second highest rate number of death-penalty executions in the world, after China.

The resolution also urged Iran to release anyone detained solely over peaceful protests, and called for an end to “reprisals” against “human rights defenders,” protesters and their families, journalists, and individuals who cooperated with the United Nations “human rights mechanisms."

Twenty-three rights groups including international organizations recently said the “international community” should urge Iran to free activists detained “arbitrarily” including three arrested in Augustwhile planning to sue Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Iran’s delegate to the UN, Zahra Ershadi, in November said Canada’s resolution exposed a "deliberate policy of incitement to Iranophobia,” violated the UN "principles of non-selectivity and impartiality," and undermined cooperation and dialogue on human rights.

Ershadi said the resolution's co-sponsors − the US, Israel which she called “the child killer Israeli regime,” and Canada − were the "main proponents of racism, occupation, and abhorrent treatment of indigenous peoples." The sponsors were scoring political points by instrumentalizing human rights, she said.

Although Iran often cites violations in Western countries as an indirect way to defend itself, the issue is that there is little recourse for victims in Iran, while citizens can openly seek redress through independent courts in Western countries. There is also tight control over media in Iran and intimidation of journalists that make publication of news about violations difficult.

The growth of social media in recent years has helped expose many violations in Iran.

Lawdan Bazargan whose brother was executed as a political prisoner in Iran in 1988, argues that a diplomat who defended prison killings should not teach in a US college.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Opinion

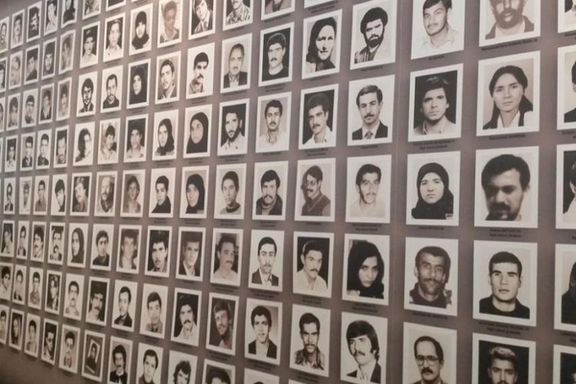

It's been 33 years, and I still don't know where my brother is buried: and I am not the only one. The families of thousands of victims of the 1988 prison massacre in Iran have never received so much as an acknowledgment from the regime that it ever happened. Moreover, one of the top diplomats from that time, who was covering up the crime, now flourishes as a professor at a top American college. The school has so far refused to hold him accountable. Americans committed to human rights should refuse to be silent. It's time Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, the so-called peace professor at Oberlin College, answer for his crimes.

When the Iranian Revolution happened in 1979, my brother Bijan was a college student in London. He was a brilliant man with his whole life ahead of him. At the same time, Mahallati—now a professor at Oberlin College in Ohio—studied in a college in the United States. Despite my parents' pleas, Bijan returned home soon after the revolution to help rebuild his homeland. He joined one of the country's leftist parties challenging the oppressive Islamic regime that weaponized religion to suppress dissident voices and was soon arrested, jailed, and tortured for years without an indictment.

Meanwhile, Mahallati returned to Iran too and climbed the political ladder. He was named spokesman for the Islamic Republic of Iran's Foreign Ministry, preaching the virtue of Islamic values and becoming one of the faces of the Islamic regime's brutality.

Bijan eventually received a 10-year prison sentence for being a member and supporter of a leftist party. Though he suffered extreme physical and psychological abuse in prison, going on a hunger strike with fellow detainees to demand better conditions, and being denied badly needed care for a medical condition, my family and I maintained hope that we would someday reunite.

That all changed in the summer of 1988, six years and three months into his sentence, when Bijan and thousands of other political prisoners were executed by the Iranian government based on a Fatwa (Islamic Decree) issued by Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader. Bijan was buried in an unmarked mass grave. The year prior, while my brother unjustly languished in prison, Mahallati was promoted to Iranian ambassador to the United Nations. Amnesty International estimates that 5,000 political prisoners were murdered in the summer of '88 extrajudicial killings.

For the past 12 years, as a religion professor at Oberlin College, Mahallati has been helping shape the minds of American students. But the fact remainsthat by November 1988, the regime Mahallati represented at the UN was partly denying and partly justifying the executions. And despite a resolution by the UN General Assembly that expressed "grave concern" about "a renewed wave of executions in the period July-September 1988," Mahallati, in his official capacity, said the resolution was based on "fake information."

Political dissidents in Iran remain under threat of unlawful imprisonment or death, yet the eyes of the world stay closed to their struggle. As Iranian freedom of speech activist and blogger Hossein Ronaghi recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "For us, it is as if there are two Irans—the one where we live and another that you read about. Your Iran is defined by a pesky nuclear negotiation. Ours is much worse. It is a religious police state where we live in fear, with countless red lines that most dare not cross. It is a country of repression, censorship, and violence."

This isn't a story about so-called "cancel culture" or free speech on college campuses: this is about human rights as a beacon of hope and applying a standard of treatment to all people, no matter where they're born. In a letter to Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar on October 8, 2020, which still remains unanswered, I joined other family members of those killed by the government Mahallati represented, “We want Mahallati removed from his post, we want an apology, and we want to know how someone with Mahallati's past could rise to prominence at such a prestigious institution.”

I cannot sit idly by while Mahallati preaches peace when he's done so much to disrupt it. When I went to the Oberlin campus the first week of November, I hoped the administration would meet with family members of the victims and me on behalf of Bijan and thousands of others who gave their lives for a better world. Unfortunately, the administration decided to ignore us once again.

As an Iranian-American, I have long watched the human rights abuses back home viewed as a sideshow to broader international policy fights. But most difficult of all has been watching Americans who say they're committed to protecting human rights ignore the Iranian people's suffering—past and present. Human right is not a leftist issue or a conservative issue; it is the moral rod that should guide us all.

Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily the views of Iran International.

Twenty-three rights groups say the international community should urge Iran to free three activists arrested while planning to sue Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Journalist Mehdi Mahmoudian, and lawyers Arash Kaykhosravi and Mostafa Nili were arrested August 14 while meeting to plan legal action against Khamenei and other authorities for mismanaging the Covid-19 pandemic and delay in mass vaccination.

At the time the daily death toll had risen to 700, but with 58 percent of the population now vaccinated, it has fallen to around 80.

In a statement Thursday, the 23 groups said the trio were in prison for defending human rights. They have been charged with "establishing a hostile group against national security" and "propaganda against the regime," which are respectively carry possible prison sentences of by ten and one year.

The statement was signed by the United States-based Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRI), International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), Human Rights Watch (HRW), the Washington DC-based Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), Ireland-based Front Line Defenders (FLD), Article 19, United for Iran, and others.

Mahmoudian, Kaykhosravi, Nili wrote in a letter in October that they had refused an offer of freedom if they signed a pledge not to sue Khamenei.

The proposed legal action related to Khamenei’s ban in January 2021 on Iran importing Covid vaccines made in the United States and United Kingdom, when no other vccines were available.

Iran instead turned to Russia and China, but they failed to supply enough doses until August. By early August, only 3.4 percent of the population had been “fully vaccinated,” on a par with Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, but far lower than Turkey (33.4 percent) and the United Arab Emirates (73 percent), which had used the American Pfizer, British AstraZeneca, Chinese Sinovac, and Russian Sputnik vaccines.

The detained activists also said they would sue officials for allocating “millions of dollars” to state organizations with no medical expertise, such as the Execution of Imam Khomeini’s Order (EIKO), which owns Shifa Pharmaceutical, developer of CovIran Barakat. EIKO promised to deliver tens of millions of doses before the end of the summer but only 13.2 million doses of home-grown vaccines have been delivered by late November.

The meeting when the trio were arrested was at the offices in Tehran of the Society to Protect Citizen's Rights, a newly-founded and registered non-governmental organization. Two others arrested, lawyers Leila Heydari and Hadi Erfanian, were released within hours, while two others − lawyer Mohammad-Reza Faghihi and activist Maryam Afrafaraz − were freed two weeks later on bail.

Many on social mediajoined healthcare professionals including the chairman of Iran’s non-governmental licensing and regulatory Medical Council, Dr Mohammad-Reza Zafarghandi, in blaming Khamenei's ban for the level of Covid and resulting deaths.

The elderly mother of a blogger who died in custody in 2012 was assaulted by unknown individuals in Iran on Thursday when she was on her way to visit her son’s grave.

Gohar Eshghi, mother of Sattar Beheshti has been demanding justice for her son who was arrested by security forces on October 30, 2012, for his blogging activity and died a few days later, in what was believed to be a case of torture in detention.

Just before noon on Thursday Eshghi was on her way to the cemetery when two people approached on a motorcycle and one of them attacked the elderly woman knocking her to the ground. People who saw the incident took her to a hospital, with injuries, a statement released by Sattar Foundation on Instagram announced.

The statement says that one month ago security agents had detained the family to prevent them from joining other victim families from a gathering. During that arrest agents threatened the family that some people die in prison under torture, but some could also die from an accident or in an altercation. After the incident the family kept receiving anonymous threats.

Tehran says it is preparing a list of American officials and entities to sanction, after the US Tuesday designated more Iranian officials for rights violations.

Kazem Gharibabadi, who until recently was Tehran’s envoy in international organizations in Vienna, including the UN nuclear watchdog IAEA, condemned the US announcement of new sanctions and said the United States itself has serious human rights issues.

Gharibaabdi is now the head of the human rights office in Iran’s Judiciary, which has been repeatedly criticized by international human rights organizations for playing a major role in arrests of dissidents, journalists and conducting unfair trials, which in some cases end in issuing the death penalty.

Gharibabadi said, “America’s regime stands accused of the way it handles peaceful protests and should answer to the world public opinion for its violent confrontations with protesters.” He also accused the US of suppressing racial minorities and said, “George Floyd is just one example of countless human beings killed by the police.”

The US and the European Union have sanctioned many Iranian security officials for their role in Iran’s November 2019 protests when security forces opened fire on demonstrates in many cities and town killing hundreds.