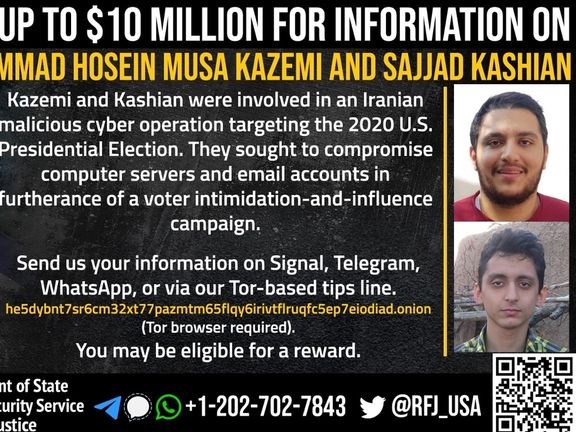

US Offers $10 Million Reward For 2 Iranians Over Election Meddling

The United States has offered up to $10 million for information on two Iranian cyber actors for trying to influence and interfere with the 2020 presidential election.

The United States has offered up to $10 million for information on two Iranian cyber actors for trying to influence and interfere with the 2020 presidential election.

The State Department’s Reward for Justice Program said in a statement on Tuesday that Mohammad-Hosein Musa-Kazemi and Sajjad Kashian sought to sow discord and undermine voters’ faith in the US electoral process.

The two contractors employed by Iranian cyber company Emennet Pasargad (formerly known as Eeleyanet Gostar) “participated in an Iranian state-sponsored, multi-phased online operation that attempted to interfere with the 2020 US presidential election” from at least August through November 2020, read the statement.

Kashian managed computer network infrastructure while Kazemi helped to carry out the campaign by compromising servers that were used to send the threatening voter emails, preparing emails for the voter threat email campaign, and compromising the email accounts of an American media company.

The cyber company provides cyber capabilities and support to Iran’s Intelligence Ministry Security as well as to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the IRGC-Qods Force – both of which are designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations.

Both hackers face sanctions and federal criminal charges in connection with their activities, the statement added.

Some media and experts in Iran warn that the middle class is disappearing amid economic crisis, with serious consequences for the government and society.

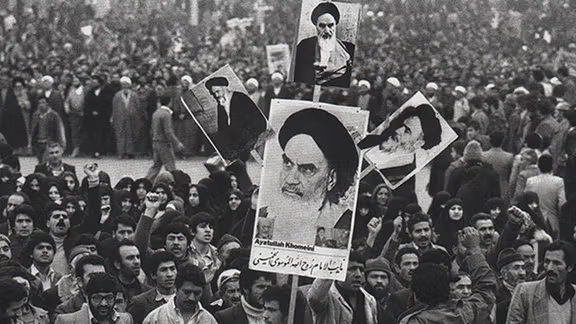

Iranian sociologist Taghi Azad-Armaki, a professor at the University of Tehran, added in an interview with Etemad Newspaper in Tehran on Tuesday, that policies by successive governments, sanctions, and a decline in Iran's per capita income have decimated Iran's middle class.

The academic argued that throughout its history Iran has often been a country with three socio-economic classes: A ruling affluent class, an underprivileged class, and a middle class that always represented the country’s values and brought about fundamental changes. He also argued that all social developments in Iran had something to do with the dynamics between social classes.

Only one month after President Ebrahim Raisi took office, as he continued to make economic promises, Eghtesad News, the country's leading economic website warned him that "The country's middle class was declining as a result of major economic crises." The website reminded that coupled with the coronavirus pandemic, the economic crisis caused by sanctions, has left the country's middle class out of breath, while also exerting massive pressure on the underprivileged people.

Meanwhile, in December last year, Hashem Pesaran, a Cambridge University academic, said that inflationary pressure and taxes annihilate the middle class and the foundations of society. There will be no middle class to read books, travel the world, learn, and teach and convey the culture of democracy.

Pesaran opined that the elimination of the middle class will inevitably lead to the destruction of the government. He argued that under the current situation, Iranian society is likely to be turned into a bipolar society in which the affluent class and the underprivileged will have to face each other in a fierce confrontation.

"A conflict will certainly take place and that is very dangerous. The former will be blinded by pride and the latter by grudge. The affluent class will become increasingly conservative and will hide behind bureaucratic organizations and the angry poor people will be looking for an opportunity to attack and take revenge. When there is tsunami, everyone sinks, no matter how big their ship is," Dr. Pesaran warned.

He added that if there is a strong middle class it will act as a shock absorber that facilitates interaction between the other two classes.

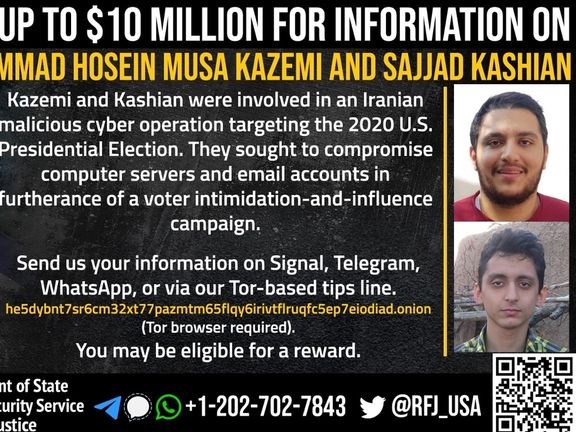

In his interview with Etemad, Dr. Armaki pointed out that the two revolutions in Iran's modern history, the Constitutional Revolution of 1905 and the Islamic Revolution of 1979 were both motivated by class struggle. The Constitutional revolution took place as the middle class joined hands with ruling class (landowners).

In the Islamic revolution, the middle class formed an alliance with the lower class to bring about a massive change. Armaki argued that in both cases the middle class was the driving force for social change. The academic further argued that the Islamic Republic has annihilated Iran's middle class because it knew that it was capable of bringing about two major revolutions in less than a hundred years. The Islamic Republic, said Armaki, has manipulated the middle class, has exerted economic pressure on it and in an optimistic scenario, it simply ignored it for decades, allowing it to decline.

Armaki said that all the post-revolution governments have contributed to this dynamic by ignoring concepts such as democracy, civil society and sustainable development. He said the reform government in mid-1990s was the only Iranian government that paid attention to these factors but came under fire by totalitarian groups and political figures.

A website for the online streaming of Iran’s state television was hacked less than a week after another similar incident disrupted a few TV and radio channels.

Hacktivist group Edalat-e Ali (Ali's Justice) hacked the television website and broadcasted a video with a strong opposition message Tuesday afternoon.

The video started with footage of people in Tehran’s Azadi stadium shouting “death to dictator” referring to Supreme Leader Ali Kamenei, then it cut into a close up of a masked man similar to the protagonist of the movie V for Vendetta, who said “Khamenei is scared, the regime’s foundation is rattling”.

The voice in the one-minute video continued that the Islamic Republic cannot silence them as they plan to turn the ten-day celebration of the 1979 revolution into mourning for Islamic Republic.

The 10-day Dawn – also known as Fajr -- is an expression used by the authorities to refer to the ten-day period between Ruhollah Khomeini's return to Iran on February 1 and to the day revolutionaries gained victory against Bakhtiar's government, the last remnant of the Pahlavi rule.

The video labeled the revolution anniversary, which is celebrated by extravagant state-sponsored events across the country, as a 10-day period for nationwide protests.

The group also announced that they are against compulsory hijab in the country, while in the background footage from a campaign by Masih Alinejad against hijab was shown.

The voiceover added that the group will expose the crimes of the regime like it did before, referring to another hack by the group when they released videos from security cameras inside the Evin prison in August 2021.

Edalat-e Ali threatened the regime with more actions and ended its video with an audio clip of people shouting “Don’t be afraid, we’re all together” that is a slogan Iranian protesters chant when security forces attack to arrest them.

The hacking group has claimed responsibility for hacking several Iranian government entities in the past three years.

In their debut action in May 2018, the group hacked into systems at Mashhad international airport and posted anti-government messages and images on arrival and departure information screens.

The group claimed in July 2018 to have hacked the email accounts of Tehran municipality officials, and the email accounts of officials of state broadcaster (IRIB) in January 2019.

Earlier on Thursday, several television and radio channels − including Channel One, News Channel, and the Arabic-language Al-Alam, as well as Javan and Qur’an radio channels -- were hacked and briefly aired photos of leaders of Albania-based opposition Mujahideen-e Khalq (MEK) with audio footage from one of their speeches in the background.

Then the video showed a photo of Iran’s Supreme leader Ali Khamenei with a red cross on it, as an off-camera voice said, “Death to Khamenei.”

Following the attack, a MEK spokesman denied any knowledge of the apparent hacking, prompting speculations that the attack might have been an inside job by the employees of the state broadcaster.

Shahin Qobadi told Iran International TV that the group had become aware of the incident only when it happened but that the hacking might have been the work of supporters in Iran.

Iran has begun discussions with both China and Russia over new airports, ILNA (Iranian Labour News Agency) reported Tuesday, despite existing ones losing money.

Managing director of Iran’s Airports Company, Siavash Amirmokri, said that after preliminary studies and negotiations, Tehran would begin talks over technical matters including navigation systems. Giving a 20- to 25-year timescale, Amirmokri said there were no immediate plans for new airports.

The semi-official news agency ISNA said in a report November 2016 that only six of Iran’s 54 airports were profitable, up from three in 2013.

The former head of Civil Aviation Organization, Touraj Dehghani Zanganeh said in March 2021 that over 90 percent of flights were concentrated in only 10 airports, with over half of the traffic at Mehrabad airport, Tehran, and Mashhad International airport.

Internal air travel in Iran is relatively common due to the country’s size, although Iran has long struggled to replenish its ageing fleet in the face of international sanctions. The reputation of Russian-made Tupolevs, used for many internal flights, dived in the early 2000s with disasters in Iran and elsewhere.

The US imposition of ‘maximum pressure’ sanctions after 2018 derailed deals Iran had agreed with Boeing and Airbus to purchase dozens of planes after international sanctions were lifted following Iran’s 2015 Iran nuclear agreement with world powers.

The Islamic Republic has begun marking the 43rd anniversary of a revolution described by its founder, Ruhollah Khomeini, as the revolution of the "bare-footed".

For decades the Islamic Republic has celebrated what is known as Ten Days of Dawn (dah-ye fajr) which marks the ten-day period from Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's arrival in Iran on the first of February 1979, to the day of the Islamic Revolution's victory, but this year's celebrations are marred not just by the pandemic but also the fact that it is much harder than ever to speak of the promises of freedom and prosperity given to masses in 1979.

Amid soaring poverty, a debate is raging among Iranians as to whether the revolution has failed in delivering on its promises. Many on social media and among activists in Iran point to government data that shows poverty has increased since 1979.

Khomeini always insisted that the revolution belonged to the mostaz'af, a Qur'anic word which means disempowered, oppressed, underprivileged, suppressed, or poor. He often used the word mostaz'af together with the "barefooted", "slum dwellers", and the "deprived". In his speeches he often said the Islamic Revolution was the revolution of "slum dwellers" against "palace dwellers" and could not survive without their support. Four decades later, however, poverty has not only persisted, but has been growing at a faster pace in recent years.

According to official figures released by the interior ministry, in total, around 60% of the 84 million Iranians live under the relative poverty line of whom between 20 to 30 million live in "absolute poverty". In 2010, for instance, the number of those living under the absolute poverty line was around 10 million according to government statistics.

Economic failures of the regime are becoming more and more difficult to justify, even given US sanctions. "The main reason for the [economic] problems [in the past ten years] is not just the sanctions. A major part of these were caused by wrong decisions and inefficiency," Supreme leader Ali Khamenei admitted in a speech Sunday.

Khamenei who charts the country's macro-policies, including the economy, takes no personal responsibility for the failures. Instead, in a speech last week he cast the blame for the troubles on President Ebrahim Raisi's predecessors, Hasan Rouhani and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and their governments.

Since 2017, Iran has seen several major protests fueled by economic demands rather than any specific political issue. The driving force of the unrest, including the nationwide November 2019 protests following an increase in fuel prices that left hundreds of protesters dead, and the 2021 water shortage protests in Khuzestan and Esfahan, were mainly the impoverished groups of the Iranian society rather than political groups and parties.

Even some of the most ardent supporters of the revolution and Khomeini's legacy are now questioning the outcome of the revolution. "One must ask, wouldn't much of the services [offered to the people] and the progress made happen anyway even if there was no Islamic Republic?", the Society of Combatant Clergy (Majma-e Rohaniyoun-e Mobarez), a reformist clerical group which is one of the oldest political groups in the country asked in a statement Sunday issued on the anniversary of the Revolution. "It is difficult to speak of the Islamic Revolution…and acclaiming it is even harder," said the statement.

The Combatant Clergy also warned that the Iranian society is now facing major economic, political, cultural and international crises including impoverishment and shrinking of the middle class. "People are saying forget about free water, electricity and cheap housing promised to us [by Khomeini and the revolutionaries], at least provide our most basic needs," the statement said.

The Combatant clerics who alleged that the Revolution has "deviated" from its original goals of providing freedom and prosperity to people also pointed out in their statement that anti-government protests are now more driven by economic demands than political reasons.

The allegation of deviation from revolutionary ideals of freedom and prosperity has angered the hardliners in power who find it very difficult to justify the various crises, including the crisis of poverty even by blaming the US sanctions.

Javan newspaper, affiliated with the Revolutionary Guards argued that when Khomeini said the 1979 Revolution was for the mostaz'af, he did not mean the economically poor but those who were "politically oppressed". "One can never say the roots of [the revolution] lay in the [demands of the economically impoverished] classes," Javan wrote.

Political activist and journalist Keyvan Samimi (aka Samimi Behbahani) has been freed from prison after he said Iranian authorities were slowly killing him.

Samimi's lawyer, Mosafa Nili tweeted late Tuesday local time that after a report by a doctor's report that his health was deteriorating, he was freed from prison

In a letter from Semnan prison published earlier in the day, Samimi explained he had been transferred to Semnan while suffering from heart problems and facing stress.

"It seems that these pressures may never end,” he wrote, suggesting he was being submitted to “burnout or gradual murder.”

Samimi was sent to Semnan from Gohar Dasht Prison in Karaj, also known as Rajai Shahr, where most inmates are common criminals including murderers. He was originally in Evin prison, Tehran, after being sentenced to three years in 2020 over his coverage of labor unrest the previous year.

According to the Iranian Writers' Association, Samimi was likely sent to Semnan, seen as a form of internal exile, because he described as murder the death of jailed writer Baktash Abtin from Covid-19 complications after he was allegedly denied timely treatment early in January.

Last week, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) expressed concern for the lives of three jailed activists, including Samimi, who it said had been transferred to jails known for “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, in a practice often used to deliberately break the resistance of prisoners of conscience.”