Fire Contained At Iran’s Oldest Refinery

Abadan refinery in south-west Iran, which supplies around 25 percent of the country’s fuel needs, caught fire Thursday.

Abadan refinery in south-west Iran, which supplies around 25 percent of the country’s fuel needs, caught fire Thursday.

Hakim Ghayyem, the refinery’s managing director, told IRNA Thursday afternoon the blaze had been contained with no fatalities or injuries, and that an investigation was underway into the damage and cause. The fire broke out at 10.32am, with some reports blaming faulty insulation.

Abadan, near the Persian Gulf coast, is Iran’s largest refinery with a daily capacity of 430,000 barrels of crude, producing liquefied petroleum gas, gasoline, kerosene, gas oil, jet fuel, furnace oil, bitumen, petroleum solvents, sulfur, and naphtha.

China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation (Sinopec) signed a $1-billion deal in 2017 to expand the refinery. Work on a second phase of the project was suspended in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Abadan, opened in 1912 by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company originally as a pipeline terminus, quickly became one of the world's largest refineries and was an important supplier to the British military.

Earlier in April, an explosion and fire in the Bandar Mahshahr Petrochemical Special Economic Zone in southern Iran injured at least two workers. Several explosions and fires in Iranian military and industrial sites − including pipelines and refineries − since mid-2020 have not been fully explained by authorities.

International non-profit organization Reporters Without Borders (RSF) called on the United Nations Wednesday to take swift action to ensure Iran followed “international human rights law” over the treatment of jailed journalists.

“The advocacy group is alarmed about imprisoned journalists who are denied medical care when they are ill,” RSF said, referring to activist Narges Mohammadi and photojournalist Alieh Motalebzadeh, who are in Qarchak women’s prison, also known as Shahr-e Rey, where health and sanitary conditions are poor and the infirmary ill-equipped.

“Under international human rights law, Iran’s prison authorities have an absolute obligation to ensure the health and well-being of detainees placed under their control by providing them with appropriate, adequate and timely medical care,” said Reza Moini, head of RSF’s Iran-Afghanistan desk.

Mohammadi’s lawyer Mostafa Nili said Tuesday that his client had been deprived of medicine for a week, including pills prescribed after a heart operation.

Reza Khandan Mahabadi, a 60-year-old journalist, was also returned to his prison cell April 5 despite respiratory problems after being hospitalized in January with a severe case of Covid-19.

The number of executions in Iran doubled in the second half of 2021 -- around the time when President Ebrahim Raisi took office -- according to figures compiled by two advocacy groups.

Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran 2021, published by Oslo-based Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO) and Paris-based Ensemble Contre la Peine de Mort or ECPM (Together Against the Death Penalty), highlighted the rise in numbers and a lack of transparency in both procedures and legislative framework.

The report said at least 333 people were executed in 2021, two thirds in the last six months. This was up from 267 in 2020, with at least 183 executions (55 percent) in 2021 for murder and at least 126 for drug-related offenses. At least two juvenile offenders and 17 women were among those executed.

"The execution rate accelerated after the election of Ebrahim Raeisi as president in June, and doubled in the second half of 2021 compared to the first half", the report said.

At least 139 followed sentences passed by Revolutionary Courts, which have different procedures to other courts, bringing the total of such cases to over 3,758 since 2010.

The report said that 278 executions in 2021 were un-announced by the authorities, and that other executions had not been included due to researchers’ inability to confirm facts.

For the first time in over 15 years, no public executions were reported in 2021 as Iran halted the practice due to Covid-19 restrictions. After a lapse of around 18 months, three sentences of public execution have been passed since March.

Iran's Central Bank Governor said Wednesday Tehran has already received the £400 million paid by Britain before the release of two British-Iranian detainees and the funds are being used.

"We have already received the money paid by Britain and the funds are even being used," Ali Salehabadi, governor of the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) told reporters. "Information on the [release of the] rest of [Iran's] blocked sums will gradually be provided. Generally, the work is progressing well," he said without any further details on the sidelines of a cabinet meeting Wednesday according to the official news agency IRNA.

Salehabadi made the remarks hours after a report by UK's The Guardian which quoted a senior Iranian government source as saying that the £400m was still blocked in Oman. The official told the Guardian that the problem was not with the UK government.

Speaking to Entekhab news website Sunday, Mahmoud Abbaszadeh-Meshkini, spokesman of the Iranian parliament’s national security and foreign policy committee, had also said that Britain's £400m debt was "released at the source", adding that the transfer, presumably to an Omani bank, had not been problematic.

The important matter was to release the frozen money from the source country, Britain, he said, adding that he believed further stages -- meaning transferring the money to Iran from Oman – could not cause any problems.

Neither the CBI governor, nor Abbaszadeh-Meshkini, elaborated on the nature of the difficulties expected in repatriation of the funds from Oman which they only referred to as a "regional" or "neighboring" country.

"The extent of the hold-up is not clear, and it is unknown whether it is due to a banking problem in Oman or another issue, such as the limits set on the use of the money by the British," The Guardian wrote.

Britain owed the £400m ($530m) to Iran for 1,750 Chieftain tanks and other vehicles purchased before the Islamic Revolution of 1979 almost none of which were delivered.

On March 16, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that two British-Iranian dual nationals detained by Iran had been freed and would be returning home. Simultaneously, some Iranian state-affiliated media, including the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC)-linked Fars news agency, reported that the two detainees had been freed in exchange for Britain's £400m historical debt to Iran.

The British and Iranian governments both claimed there was no connection between the debt and the case of detained individuals.

According to the Guardian, "one report" said only £1m of the money had been transferred to Tehran.

Muscat mediated for the release of the two UK detainees, Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Anoosheh Ashouri, who were freed after the funds arrived in an Omani Bank.

The Guardian also said there had been speculation that London may be withholding full release of the funds because it believes Iran has not kept its side of the negotiated bargain that should have allowed a third detainee Morad Tahbaz indefinite leave from prison. He was briefly released and then returned to prison.

The UK Foreign Office has stressed that the payment, made on the condition that it would be used only for humanitarian purposes, “was made in full compliance with UK and international sanctions and all legal obligations”. Iranian officials have said that Tehran has "full control" on how to spend the funds without a mention of the conditions set by Britain.

Iranian investigative journalist Hossein Dehbashi has been exonerated in a lawsuit filed against him for saying that the son of the founder of the Islamic Republic died of "drug abuse".

Dehbashi said in a tweet on Wednesday that the complaint by the institute for the works of Ruhollah Khomeini as well as his grandson Hassan for publishing lies and insulting Ahmad Khomeini was rejected.

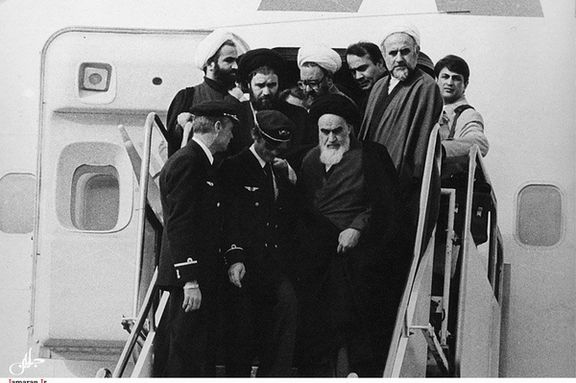

In February, he tweeted the picture of Ruhollah Khomeini disembarking from a plane in Tehran in February 1979, after a 15-year exile, explaining what happened to those who accompanied him on the flight.

In the post, Dehbashi had said that the reason for Ahmad Khomeini's death was "drug abuse", which led to a barrage of criticism against him.

He later deleted the post but said in reaction to critics that he heard the allegation from Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who was the most influential man in the Islamic Republic, second only to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Khomeini's son, Ahmad, who also accompanied his father in the return journey and was his confidant until the ayatollah's death, died in a mysterious incident in 1995 that was reported as a heart attack.

Another journalist, Emadeddin Baghi, quoted regime insiders as having said that former deputy intelligence minister Saeed Emami had confessed to Ahmad Khomeini’s killing.

Emami was also accused of having independently organized the "chain murders" -- a series of 1988–98 murders and disappearances of Iranian dissident intellectuals who had been critical of the Islamic Republic.

A member of parliament says the shortage and high prices of medicines in Iran are not limited to certain drugs anymore, and very common medications are also scarce and expensive.

Homayoon Sameh Yeh Najafabadi, who is a member of the parliament's health committee, told ILNA on Wednesday that “today medicine has become very scarce in the country, not special medicines but very ordinary medicines. Therefore, people have to go to several pharmacies for one prescription”.

Criticizing those who claimed to be able to control the prices of medicines, he added that the Health Ministry should have devised a detailed plan for controlling the prices before submitting the budget bill to parliament.

Many officials from the Health Ministry appeared before the parliament and said there would be no problem with the high cost of medicines because the insurance companies would cover the higher in prices, and that there won’t be any pressure on patients once subsidy for imports of essential goods are eliminated, Najafabadi said.

The lawmaker said in addition to medicines, the prices of wheat, flour and bread have also increased, expressing hope that the government has a plan in this regard.

In March, the parliament decided to scrap an annual $9-14 billion subsidy for essential food and medicines, despite warnings of more inflation and hardship.

The subsidy was introduced in April 2018 when former US president Donald Trump signaled his intention to withdraw from the Obama-era nuclear agreement with Iran known as JCPOA, and Iran’s national currency began to nosedive.