Controversial UN Rapporteur Calls For Unfreezing Iran Assets

A UN Special Rapporteur on sanctions has called on countries to unblock Iran's "$120 billion assets" frozen in foreign banks, so Tehran can fulfill its human rights obligations.

A UN Special Rapporteur on sanctions has called on countries to unblock Iran's "$120 billion assets" frozen in foreign banks, so Tehran can fulfill its human rights obligations.

Alena Douhan, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Negative Impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures on the Enjoyment of Human Rights, made the remarks during a press conference in Tehran on Wednesday.

“I urge the states that have frozen the assets of Iranian Central Bank to immediately unfreeze Iran’s funds based on international law”, she said, adding, “I call on the sanctioning states, particularly the US, to abandon the unilateral sanctions”.

Douhan claimed that decades of sanctions have wholly affected Iranian people’s lives and have particularly hit the low-income section of the society.

Several human rights advocacy groups have protested her visit to assess the impact of sanctions on Iran, calling it Tehran’s attempt to divert attention from its human rights violations.

Iran has not allowed visits to any of the fourteen UN human rights experts who have made requests to monitor the situation in Iran, including to the special rapporteurs appointed by the UN Human Rights Council.

The role of the sanctions’ rapporteur was created at the UN Human Rights Council by the adoption of a resolution proposed by Iran on behalf of Non-Aligned Movement in 2014.

Since her appointment in March 2020, Douhan has mainly campaigned against the United States and its allies’ sanctions policy. She is a professor in Belarus, one of the biggest human rights violators, but is not on record criticizing massive crackdowns in her home country.

Tehran has announced that in the first month of the Persian year 1401 (April 2022), Iran’s non-oil exports grew 25 percent compared to the same month last year.

This growth follows a 40 percent increase in the country’s non-oil exports over the entire previous year, which reached $48 billion — a gain made possible by loose sanctions enforcement and global inflation in 2021.

When the Trump administration withdrew in May 2018 from the Iran nuclear agreement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the reimposition of U.S. sanctions cut Iran’s GDP growth, put downward pressure on Iran’s oil exports, caused massive inflation, led to an exodus of foreign companies from Iran, and limited Iran’s access to both its foreign reserves and its oil and non-oil export revenue.

Under pressure from sanctions, Iran’s oil exports declined significantly. Tehran exported 2.6 million barrels per day in June 2018, the month after Washington withdrew from the JCPOA, but its exports fell to 800,000 barrels per day in December 2018 and further slid to 385,000 barrels per day in May 2019.

From there, Iran’s oil exports climbed upward, but have yet to return to their June 2018 high. Iran exported 555,000 barrels per day in December 2019, 1.1 million barrels per day in December 2020, 1.4 million barrels per day in December 2021, and 1.1 million barrels per day in April 2022, according to the UANI’s tanker tracker.

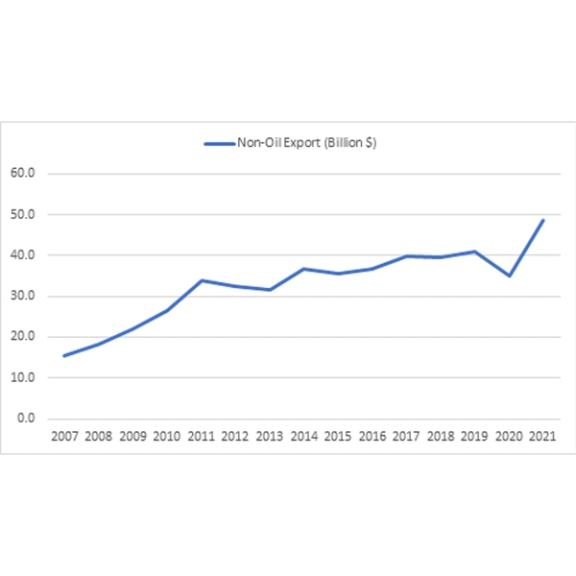

The sanctions against non-oil exports, however, failed to exert a comparable downward pressure. In 2017, Tehran exported $39.9 billion of non-oil goods. The following year, its exports slightly dropped to $39.6 billion, but in 2019 they jumped to $41 billion. Only in 2020, mainly driven by the pandemic-caused global recession, did Iran’s non-oil exports drop to $35 billion. A year later, though, Iran’s non-oil exports reached their peak of $48 billion.

Still, the removal of non-oil sanctions may lead to a further 15 to 25 percent increase in non-oil export revenue and will make that revenue more accessible than it now is. Given the lack of detailed data for Iran’s non-oil exports over the last few years, I reach this number by considering the change in prices during the forecast period against the price levels during the Persian year 1400. I use an average of oil price and the S&P GSCI Non-Energy Commodities index to create Iran’s exports basket. This assumption is based on the 50 percent share of oil-based products in Iran’s non-oil exports. As an alternative I create Iran’s export basket using the oil price and Global Price of Non-Fuel index. I then use the change in Iran’s exports from 2015 to 2016 (the year after the nuclear deal), with price changes taken into account, and use it to estimate how return to the revised JCPOA will affect Iran’s non-oil exports.

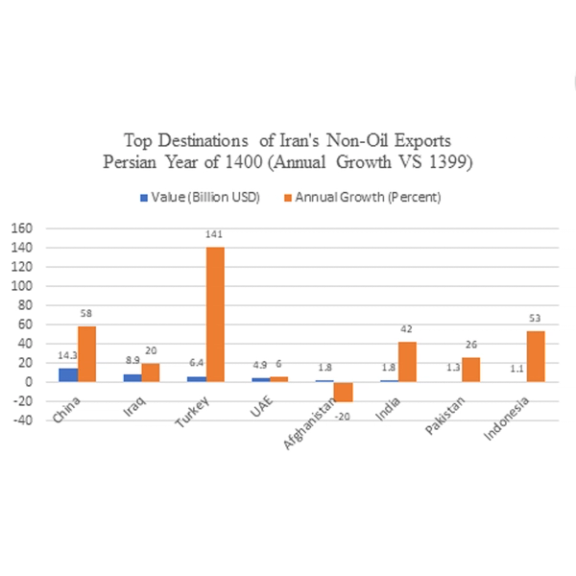

According to a report by the state-run Trade Promotion Center of Iran, key items in Iran’s non-oil exports were natural gas at $4.9 billion and 84 percent growth, polyethylene at $3.1 billion, methanol at $2.2 billion and 87 percent growth, and liquid propane at $1.9 billion and 96 percent growth. Four countries served as the destinations for 70 percent of Iran’s total non-oil export: Tehran exported $14.3 billion to China, $8.9 billion to Iraq, $6.1 billion to Turkey, and $4.9 billion to the United Arab Emirates.

Source: Central Bank of Iran

The Central Bank of Iran’s data show a trend of consistent growth in Iran’s non-oil exports over the last 15 years. Two waves of sanctions — 2010-2013 and 2018-2020 — disrupted this upward trend but have failed to stop or reverse it. The massive jump in the Persian year 1400 (April 2021-March 2022) to $48 billion was driven largely by higher prices. This conclusion is based on a review of the weight of some key items in Iran’s exports such as methanol. However, due to lack of detailed data for all items, the conclusion is not definitive.

Source: Trade Promotion Center of Iran

The lax enforcement of non-oil sanctions has also played a role. Non-oil products are heterogenous and much easier to repackage, hide, and re-export, so enforcement is more difficult. Furthermore, many of Iran’s neighbors are keen to ignore Tehran’s sanctions busting activities, hoping to take advantage of related business opportunities. Even so, Washington could have enforced non-oil sanctions more effectively if it had decided to allocate more resources and political capital to its efforts.

If the United States lifts sanctions pursuant to a revised nuclear deal, Tehran’s non-oil exports could reach $55 billion to $60 billion in the first year of the deal. By increasing Iran’s oil and non-oil exports, lowering the cost of imports, and granting Iran newfound access to its foreign currency reserve, a revived JCPOA may provide Tehran with a financial package worth up to $275 billion in a 12-month period.

US State Department says most of the punitive measures against Iran is imposed on its Revolutionary Guard, putting them among the most heavily sanctioned entities in the world.

The department's spokesman, Ned Price, told a briefing on Tuesday that out of the 107 sanctions the Biden administration has imposed on Iran, 86 – some three-quarters – have been applied against the IRGC or its proxies.

He added that “there are various authorities we can use when it comes to the IRGC... In addition to the FTO, there are a number of other authorities that are used to constrain and constrict its activities and those of its leadership and its proxies as well”.

“The fact is that we do have a number of tools, but whether it’s the SST (State Sponsor of Terrorism), whether it’s the FTO (Foreign Terrorist Organizations) designation, both of these things are defined by statute”, Price said in response to a question about their efficacy, adding that “we are going to follow the law. We’re going to do what’s in our national security interest when it comes to every authority under the sun”.

Talks to revive Iran's 2015 nuclear deal with world powers have stalled since March, chiefly over Tehran's insistence that Washington remove the FTO designation of the IRGC, which is the only example of a sovereign state’s armed forces to be included.

An Iranian lawmaker has called on the authorities to tell the people that the Vienna talks to restore the 2015 nuclear deal will yield no results.

Mahmoud Ahmadi-Bighash, who is a member of the parliament's National Security and Foreign Policy committee, said on Saturday that there is no news about the revival of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) because it has reached a dead-end.

He said the fate of the JCPOA is entangled with the lives of people and they are subconsciously invested in the talks, therefore “if we tell people the truth about the JCPOA... they will know what to do”.

“Our differences with the United States and the Europeans are fundamental”, he noted, saying that “the Americans believe that we should give up our principles while we want them to give up their arrogant and bullying behavior”.

Ahmadi-Bighash added, “We cannot give up our revolutionary principles because they are inherent in our religious obligations”, claiming that the issue of the Revolutionary Guard being listed by the as a terrorist organization by the US is just an excuse.

He praised relations with Russia and China and emphasized the Islamic Republic's motto of "self-reliance", but except Israel, the lawmaker said, Iran should have relations with all counties.

Negotiations, which started in Vienna in April 2021 to revive the Obama-era nuclear deal, JCPOA, have been on a protracted pause since March 11, as the Islamic Republic demanded removing its Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) from a US list of terrorist organizations.

Iran’s currency, rial hit a four-month low on Saturday against the US dollar, as soaring bread prices created political and economic uncertainty in the country.

The US dollar rose to 285,000 rials in Tehran, the highest point since early January, when the currency was marginally recovering from previous lows on optimism over nuclear negotiations with the West. After talks in Vienna came to a standstill in mid-March, the currency began gradually losing its value again.

The rial has fallen almost ninefold since late 2017 when signs emerged that former US president Donald Trump intended to withdraw from the 2015 nuclear agreement, JCPOA, and impose economic sanctions on Iran.

Trump eventually pulled the United States out of the Obama-era agreement in May 2018 and imposed oil export and other sanctions that began to squeeze Iran’s oil-dependent economy. High double-digit inflation and a falling currency followed, leading to at least two years of a deep recession.

The falling currency makes everything else more expensive for people who earn depreciated rials. Key foodstuff, such as cooking oil, and 15 million tons of wheat are imported annually. In addition, animal feed is also imported and a falling currency makes meat and poultry more expensive. Most Iranians have stopped buying meat according to industry people in Iran.

This week the government finally acted on an earlier decision to stop a subsidy in the form of cheap dollars for imports of essential commodities, such as flour and animal feed. Immediately, cooking oil disappeared from supermarket shelves and flour prices increased fivefold, leading to a bread crisis.

The government’s handing of the price jump has been haphazard, claiming to be ready to provide cash assistance to citizens for buying bread but offering contradictory information on how the process would work. Pundits and citizens have reacted by saying that apparently the government failed to prepare for the eventuality.

There were reports on Friday of bread protests breaking out in the oil-rich Khuzestan province

President Ebrahim Raisi and his oil minister Javad Owji have been insisting that Iran’s illicit oil exports and revenues have risen in the past year, with evidence that Iran has been exporting anywhere between 750,000 to one million barrels per day. However, the economic impact of higher oil revenues is nowhere to be seen.

The key to lifting US sanctions and getting a reprieve form economic pressure is reaching an agreement with the United States over the nuclear issue, but talks in Vienna have stopped since mid-March.

As bread prices shot up almost fivefold in two days, economy minister Ehsan Khandouzi promised Saturday that the government will start a system of cash assistance to buy bread, but his statement was vague as to who what income groups would be eligible to receive the cash subsidy.

Meanwile, Hamshahri newspaper reported that the government is also planning to hike the price of cooking oil and gasoline, to begin reducing decades of subsidies paid by oil export income.

A gasoline price hike in November 2019 led to nationwide protests in which security forces shot dead at least 1,500 people and arrested 8,000.

Prices for all these commodities are very low in Iran compared to other countries, but so are wages. An Iranian worker earns an average of $150 per month and when one flatbread costs one dollar, the family can only afford to buy 3-4 breads a day, and nothing else.

The Biden administration's negotiating team have reportedly acknowledged in private that an agreement that would go beyond curtailing Iran’s nuclear program is no longer possible.

Politico cited multiple people familiar with classified Congress briefings on the subject that the two Iran-related motions passed in the Senate on Wednesday were a warning shot to the US team negotiating restoring the 2015 agreement with Tehran.

Although the motions were non-binding, the vote was seen as a test run of the bipartisan rebuke that would likely happen if Washington and Tehran clinch an agreement that does not address Iran’s non-nuclear activities and removes Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (IRGC) from the list of foreign terrorist organizations.

The measures -- that for the first time forced lawmakers to go on record about the key sticking points in the year-long negotiations in Vienna -- were also hailed as modest victory for Republicans who have been urging the Biden administration to walk away from the talks, now in limbo for weeks now.

The first vote on Wednesday was proposed by Senator Ted Cruz that called for maintaining terrorism-related sanctions on Iran’s Central Bank to limit Tehran’s cooperation for China, while the other – led by Senator James Lankford instructed Senate conferees to make sure that a House bill would include language that the Biden administration cannot remove the terror designation of the IRGC.