Iranian singer Mehdi Yarrahi receives 74 lashes, lawyer says

Iranian singer Mehdi Yarrahi, known for his protest songs in support of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, received 74 lashes as part of his sentence, his lawyer said on Wednesday.

Iranian singer Mehdi Yarrahi, known for his protest songs in support of the Women, Life, Freedom movement, received 74 lashes as part of his sentence, his lawyer said on Wednesday.

Zahra Minooei confirmed on X that the flogging was carried out at Branch Four of the Moral Security Prosecutor’s Office in Tehran, marking the conclusion of Yarrahi's case. "The flogging sentence has been carried out," she said.

Yarrahi, who was arrested in August 2023 after releasing a protest song titled Rousarieto (Take Off Your Headscarf), had previously been sentenced by Tehran’s Revolutionary Court to two years and eight months in prison, a cash fine, and 74 lashes.

He was sentenced to two years and eight months in prison, with one year enforceable under Iranian law. He was temporarily freed after posting bail of 150 billion rials (around $170,000) and, according to his lawyer, the prison term was later converted to house arrest with an ankle monitor due to health conditions.

"We wanted to lift the bail, but they said it was conditional on the flogging sentence being carried out," Minooei said.

Before the flogging was carried out, Yarrahi had said that he would not request the cancellation of the lashing sentence.

"I announced in the media that I condemn this sentence, but I am ready for its execution," he said in a video posted last week.

The singer gained prominence for his support of the 2022 popular protests, ignited by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in custody of hijab police.

He was convicted of charges including producing, sending, distributing, and publishing obscene and immoral content, encouraging corruption, and propaganda against the system.

His case highlights the ongoing crackdown on artists and musicians in Iran who express dissent, with other singers like Toomaj Salehi and Saman Yasin also imprisoned for their support of the uprising. Although both have since been released.

Iran has taken hostage at least 66 people since 2010, UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Alice Jill Edwards reported on Tuesday, criticizing Tehran's detention of civil society figures and dual nationals for political ends.

"At least 66 cases of State hostage-taking in the Islamic Republic of Iran have been reported since 2010," the report released on Tuesday said.

"Journalists, aid workers, academics, business travelers and human rights defenders are especially vulnerable," it added. "Dual nationals are often specifically targeted, and, in some cases, those individuals have been denied consular assistance from their other country of nationality."

The report covered hostage-taking in an array of countries and cited an International Court of Justice ruling that states like Iran and not just militant groups take part in the practice.

Iran denies a policy of hostage-taking but has repeatedly seized dissidents, foreigners and dual nationals in exchange for its detained nationals and economic concessions.

“Hostage-taking is cruelty – plain and simple – and almost always involves torture,” Edwards said. “It inflicts severe physical and psychological suffering on both hostages and their families.”

The German embassy in Tehran is investigating reports of the detention of a German national and has raised the matter with Iranian authorities, a source from the German Federal Foreign Office told Iran International on Sunday.

As a diplomatic standoff over Tehran's disputed nuclear program deepens, Iran has been detaining more Western citizens.

Iran last month charged a British couple in the midst of a worldwide road trip with espionage. The United Kingdom is one of three European countries involved in ongoing talks with Tehran over the nuclear dossier.

Another, France, has protested Iran's continued detention of three of its nationals.

Iranian actress Chakameh Chamanmah said authorities have summoned her to the judiciary without pressing charges eight months after she was banned from leaving the country following her return to Iran.

Following the summons, Chamanmah said that while no official charges have been mentioned, she would appear before the judiciary with her lawyer.

She said she has been subjected her to repeated interrogations without a judicial order since her return to the country out of what she called love for her homeland.

The young actress was stopped at Tehran's Imam Khomeini Airport upon arrival, where her passport was confiscated and she was given an instant travel ban.

Since then, she said, "I have been repeatedly interrogated and questioned by various security agencies without a judicial order and, in some cases, faced mistreatment and insulting behavior.

"While government officials constantly talk about the return of Iranians abroad, from the moment I returned to my homeland, I have not been allowed even a single day to live in peace."

Chamanmah's summons comes just days after the directors and lead actors of My Favorite Cake, an Iranian film that premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival, went on trial in a court in Tehran, alongside other members of the production team.

Iran's entertainment stars have been among scores placed under such punishments as travel bans alongside the likes of sports figures in the wake of the 2022 uprising, many of whom having supported the Woman, Life, Freedom protests.

Other punishments included pay freezes, fines and sackings, causing a surge of stars fleeing the country.

A woman in Tehran died after her veil became entangled in an escalator, marking the latest fatal accident linked to country's mandatory hijab laws.

The incident took place in eastern Tehran's Damavand Street last Thursday, according to a report by Tehran-based Didban News website.

Although the report referenced other incidents involving malfunctioning and poorly maintained escalators, it noted that the direct cause of this woman's death was her hijab getting caught.

The case is not the first time Iran’s compulsory hijab rules have been linked to fatal accidents involving women.

On November 7, 2021, Iranian media reported that 21-year-old Marzieh Taherian died at a spinning workshop in Semnan, northern Iran, after her headscarf became caught in a machine, pulling her head inside.

On June 5, 2023, a 26-year-old female worker at a plastic injection molding workshop in the northeastern Iranian city of Neyshabur, lost her life when her veil became entangled in a machine, dragging her into it.

The incidents highlight the potential safety risks associated with mandatory hijab in workplaces and public spaces.

On Monday, UN rights chief Volker Turk urged Iran to permanently repeal its hijab laws and end along with all other laws and practices that discriminate against women and girls.

However, despite multiple fatalities in recent years, and repeated calls from rights groups and UN officials, Iranian authorities continue to enforce mandatory hijab laws on women and girls.

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Turk urged Iran to permanently repeal its hijab law and end its use of the death penalty, speaking at the 58th session of the Human Rights Council on Monday.

"I call again on the authorities to repeal the (hijab) law fully and permanently, along with all other laws and practices that discriminate against women and girls," Turk said.

In December, Iran postponed the implementation of the controversial hijab law that imposes severe penalties on women and girls who defy veiling requirements, following huge backlash from the public and the international community.

Despite this, Iranian authorities continue to crack down on women who appear unveiled in public.

He also called for the release of all detained human rights defenders and an end to arbitrary arrests and imprisonment. Expressing concern over a sharp rise in executions, Turk noted that more than 900 cases were reported last year.

"I have urged the Iranian authorities to place an immediate moratorium on the use of the death penalty," he added.

At least 54 political prisoners are currently on death row in Iran, according US-based rights group Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA), with 19 having their convictions upheld by higher courts of the Islamic Republic

In 2024, a total of 31 women were executed in Iran, the highest annual number in 17 years.

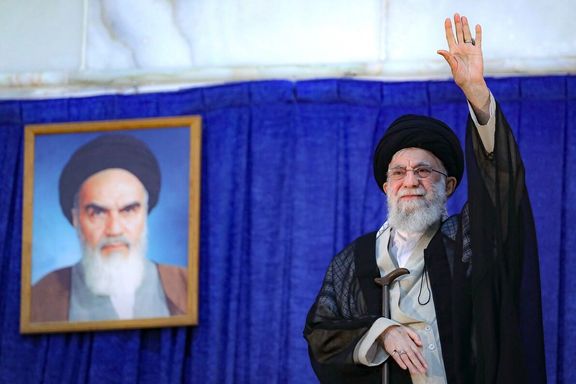

Last week I took my teenage niece to a concert at Tehran’s iconic Vahdat Hall, where two large portraits hang high on stage walls, watching over the audience. “What’s the Islamic Republic doing here,” my niece joked.

The portraits, to be clear, are those of Iran’s current and former supreme leaders. I’m leaving out their names because to my niece, they are one and the same. Not just them, but all the turbaned guys. And not just to her, but to most in her generation.

We, the so-called Millennials, fought the Islamic Republic. Iran’s Generation Z has disentangled itself from it. It has no time for it, lives in a parallel reality almost, detached from all that the state stands for and promotes.

A few weeks ago, a short video went viral of young girls struggling to name the Islamic Republic’s late and living leadership by their image.

The video was clipped from an apparently state-commissioned documentary aiming to illustrate the corrupting effects of so-called cultural invasion and rally those who care about revolutionary values.

Only, it did the exact opposite.

The image of teenagers giggling as they fail to identify the leaders underscored the proposition, often dismissed as wishful rhetoric, that the aging Islamic Republic will not survive the spice and sass of Iran’s generation Z.

The documentary, whatever its aim, showcased the profound disconnect between Iran’s rulers and its youth. What it also showed was how effortlessly cool the latter are about it.

“We cannot care less,” the girls’ body language seemed to say. “We really don’t,” my niece confirms this when I put this idea to her.

For those of us who grew up in the early years of the Islamic Republic, the contrast is striking. Not only did we know—and fear—our rulers, but we chanted and prayed for their health every morning at school.

We were steeped in propaganda, with little exposure to the outside world. The state broadcaster was the only show in town. Today, most homes have satellite TV, even though it’s illegal. And most teenagers are on social media, even though many platforms are filtered.

This access to all that’s out there has transformed Iran from within and below, even if the shell and the top remain the same. In her attitude toward religion and authority, my niece has much more in common with a teenager in the United States than she has with her mother.

I have a home video of my older brother’s birthday party from the mid-1980s, discovered in a house move and digitized a few years ago. Uncles, aunties and cousins dance to an Iranian pop song.

As they move about, a framed picture on a shelf at the other end of the room emerges and vanishes behind them: an A4 print of Iran’s then supreme leader, Ruhollah Khomeini.

The contrast boggles the mind today. But at the time it was all but typical. A time when millions had a portrait of this or that cleric at home, when respect and affection for the turbaned guys was still there—waning, of course, as men in uniform stormed houses and arrested partying aunties and uncles.

Over the years, injustice and repression eroded affection and erased all such individual displays of respect. The leaders’ images are still ubiquitous, but only in public and only sponsored by the state.

My niece and her friends have never really looked at these images. They do not examine Khomeini’s face on banknotes the way we once did, trying to find the fox that was said to have been hidden in his beard by the cheeky designer.

“You must be kidding me,” my niece told me when she caught me watching a presidential debate on state-TV last summer. “Who gives a crap about elections?”

A few words later, I learned she did not even know how many were running, let alone their names.

Unlike my generation, who believed in change through the ballot box, whose priority was politics and the collective, my niece’s generation is concerned with the individual: my hair, my rights, my aspirations.

The apathy with politics and the focus on self runs deeper and broader than the teenage folk, of course. But theirs is more natural, unforced—organic perhaps. And our generation can take some credit for that.

My sister is not my mother. Her daughter, my niece, has been hearing her swearing at Iran’s officials since she was a fetus. She has not been forced by my sister to “beware and behave.” She has not been scolded for getting a low grade in Religion at school.

My sister and I were suppressed both by the state and by our parents’ fear of the state. My niece has grown up with parents not just disillusioned by but vocal against the state. Little surprise then that she is bolder almost to the point of brashness.

“What does it have to do with my mom or her mom or their dear God,” my niece says when I meekly suggest that my sister may be uncomfortable with her outfit. “It’s not like I’m asking her to dress like this, is it?”

The near-intrinsic boldness at home has left its mark on the streets as well. Just look at the leading role teenagers played in Iran’s 2022 uprising. They fought harder than their parents, not over censorship or election fraud, but for their right to live.

It was a collective of struggles for the individual. And it triumphed in the sense that it normalized uncovered hair, the very thing that had a young woman killed, sparking the widespread protest aptly called the Woman Life Freedom movement.

So our turbaned leaders may still be watching over my niece. But they’re as relevant to her life as their framed pictures are to the music that fills the concert hall she entered for the first time with me.

I still do tell her about the fights of my generation, our campaign, for instance, to gather a million signatures demanding an end to discrimination against women in Iran. She nods approvingly but you can tell she’s unimpressed.

“Why bother shouting 'leave me alone' when you can just walk away,” she lectures me. Like many of her ilk, she appears to have stopped worrying about freedom and just lives it.