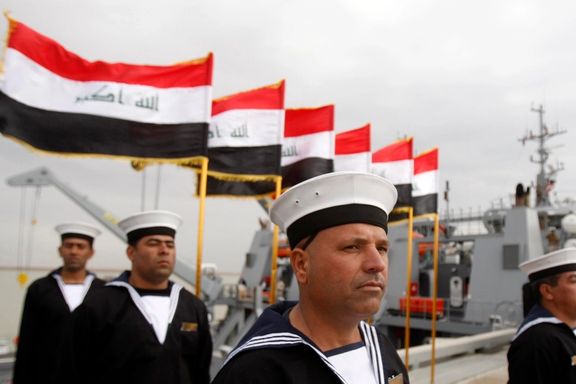

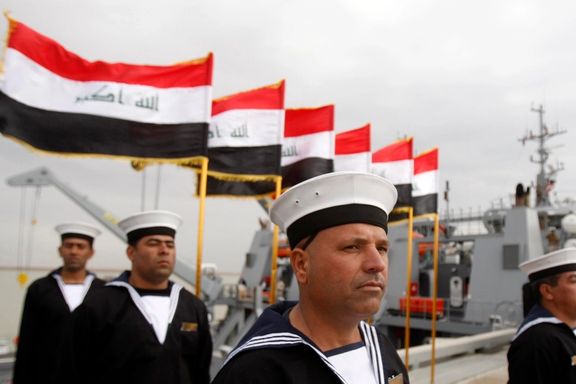

Iranian captain detained as Iraq seizes fuel smuggling ship

Iraqi naval forces seized an unidentified vessel in the Persian Gulf suspected of fuel smuggling, detaining the Iranian captain and ten Indian and Iraqi crew, the navy said Tuesday.

Iraqi naval forces seized an unidentified vessel in the Persian Gulf suspected of fuel smuggling, detaining the Iranian captain and ten Indian and Iraqi crew, the navy said Tuesday.

The vessel, intercepted in Iraqi territorial waters, was towed to Umm Qasr naval base for investigation and the crew was handed over to local police. Its name was not visible in a picture released by the navy.

Fuel smuggling is common in the Persian Gulf, where heavily subsidized fuel is sold on the black market to buyers across the region, but Iraqi seizures are relatively rare.

In December, Iran's President Masoud Pezeshkian said that 20 to 30 million liters of fuel are smuggled out of the country daily, calling it a catastrophe amid the country's energy crisis.

Pezeshkian did not specify the destinations but fuel smuggling in Iran often involves routes to neighboring countries where fuel prices are significantly higher.

In December, Reuters reported that a sophisticated oil smuggling network generating at least $1 billion a year for Iran and its proxies has flourished in Iraq since Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani took office in 2022.

Earlier this month Iranian authorities discovered and sealed four illegal taps on a major oil pipeline near the southern city of Bandar Abbas.

Last month, Iran said it dismantled 130 fuel smuggling depots and arrested 41 key suspects in Tehran province.

Iran's police chief said the new Iranian year starting on Friday will mark a significant push towards sealing the country's borders and intensifying the fight against crime.

General Ahmad-Reza Radan, the national police commander, announced on Wednesday that enhanced equipment and operational capabilities would enable a leap in border security for the Iranian year 1404.

"The border and its closure were among the challenges for the police in 1403," Radan stated, promising a decisive shift in the coming year without elaborating on details.

Up to 8 million Afghans have illegally entered Iran since 2021, compounding the country's economic challenges such as shortage of energy and water. The authorities have not been able or unwilling to commit resources to protecting the long border.

Last April, Deputy Police Chief Qasem Rezaei said that the construction of a border wall with Afghanistan would "help prevent drug trafficking, the movement of outlaws, and terrorist infiltrations."

The border fortification plan, which entails building a four-meter concrete wall, along with barbed wire, fencing, and proper roads along the northwestern and eastern borders, is scheduled for completion within the next two years.

In addition to border security, Radan outlined key priorities for the police in the coming year, 1404, including, reducing traffic violations, combating theft and the trade of stolen goods and leveling up the fight against drugs.

"1404 will be a bitter year for thieves and those who deal in stolen goods," Radan warned, as crime has increased amid the current economic crisis.

Radan detailed the extensive deployment of security forces during the Nowruz 1404 Exercise which showcased the police's readiness for the Iranian New Year holidays.

"More than 16,000 patrols, 20 helicopters, dozens of drones, and over 250,000 police personnel will secure the country from the borders to the cities," he said.

Tehran's police chief, General Abbas Ali Mohammadian, reported a 19% decrease in thefts in the capital during the past year, attributing it to increased police activity. He also noted a rise in emergency call responses and significant seizures of narcotics.

Iranian police called for public cooperation and adherence to Islamic fasting rules during the coinciding Nowruz and Ramadan periods, emphasizing that celebrations must align with Islamic rules.

While Nowruz is not officially banned, its pre-Islamic roots have long been a point of contention among religious hardliners who dominate key centers of power. These groups often discourage traditional Persian festivals, viewing them as remnants of the past that glorify pre-Islamic Persian history.

In previous years, authorities have attempted to limit gatherings at historically significant sites such as Persepolis and the tomb of Cyrus the Great in Pasargadae, sometimes leading to clashes with participants.

The Iranian year 1403 ending on March 20 marked one of the most challenging yet for the country’s ruling elite, which has been beset by economic malaise at home and historic setbacks abroad.

At the start of the year in March 2024, Iran was already grappling with a broken economy and the looming threat of political unrest. Regionally, however, it still appeared strong and could plausibly project itself as a serious challenge to US and Israeli interests.

Conflict with Israel

As the year began, Israel was deeply engaged in its war with Iran-backed Hamas in Gaza. Tehran confidently claimed that its regional adversary was stuck in an unwinnable conflict, boasting about its so-called Resistance Front and threatening to escalate against both Israel and US interests. Yemen's Houthis were already disrupting shipping in the Red Sea and launching missiles at Israel.

Houthi attacks on maritime trade which began in November 2023 following a declaration by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei inflicted an estimated $200 billion in losses on the global economy.

Less than a month into the Iranian year, Tehran launched a large-scale missile and drone strike on Israel In April 2024 in response to Israeli attacks on Iranian targets in Syria.

While most projectiles were intercepted with minimal damage, the Islamic Republic framed it as a significant blow against the "Zionist entity." At the time, Tehran appeared strong, seemingly capable of deterring its most determined adversary.

However, the tide began to turn in late July when Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh was killed in an explosion while staying at a government guesthouse in Tehran.

It remains unclear whether the incident was caused by a planted explosive or an Israeli missile strike, but the ability of Tehran's arch-foe to strike seemingly anywhere was lost on no one.

The assassination would be just one of many, crescendoing with the killing of Hezbollah leaders via their bomb-laden communication devices and culminating in the assassination of its storied leader Hassan Nasrallah.

Political crisis

Before these epochal blow, Iran suffered another major shock in May when hardline President Ebrahim Raisi and his foreign minister died in a mysterious helicopter crash in northwestern Iran.

Many doubted the official explanation of bad weather, which was never conclusively proven, fueling speculation about a high-level internal plot or an Israeli operation.

Raisi had been widely regarded as ineffective, presiding over a rapidly deteriorating economy since taking office in 2021.

In June, Iran held presidential elections, with several key candidates disqualified through a vetting process controlled by Khamenei. Ultimately, Masoud Pezeshkian, a politician with no executive experience, faced hardliner Saeed Jalili in a low-turnout runoff and won.

During his campaign, Pezeshkian made it clear that he had no plans beyond executing Khamenei’s directives.

Some Iranians still hoped for limited reforms and a diplomatic breakthrough to ease US sanctions. However, when Khamenei formally banned negotiations in early February 2025, Pezeshkian pledged loyalty to his decision, disappointing even his Reformist supporters.

Economic crisis

By mid-2024, with Hezbollah and Hamas weakened and Israel growing more confident in striking Iranian military targets, Iran’s economic woes deepened. The rial, which had been around 550,000 per dollar in September, plunged to 900,000 by February and even hit one million by March 18.

The worsening economic picture underscored a government unable to halt a downward spiral. Severe energy shortages crippled both households and industries throughout fall and winter, with the government regularly announcing power shutdowns across the country due to heating and electricity failures.

Iran’s oil exports to China continued through intermediaries and at deep discounts, but the Trump administration escalated sanctions on oil tankers and trading entities following Biden’s late-term crackdown on exports.

Revenues from these limited exports fell far short of meeting the government’s foreign currency needs, especially given Tehran’s ongoing financial commitments to regional proxy groups.

Bleak outlook

Many political insiders in Tehran now say Pezeshkian’s administration may be incapable of addressing the worsening economic crisis. The only potential relief would come from easing US sanctions, but Khamenei has so far resisted Trump’s pressure to make concessions.

It remains unclear whether Washington seeks only a binding agreement to prevent Iran from enriching uranium to weapons-grade levels or whether it also aims to curb Tehran’s ballistic missile program and regional activities.

Khamenei appears to be employing delaying tactics, hoping circumstances shift in his favor or that he can stall until the next US elections. Meanwhile, Trump continues to tighten sanctions and increase military threats, either directly or through Israel.

Another critical challenge is the risk of public unrest due to soaring prices and a growing sense of political instability.

While the Islamic Republic has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to use deadly force against protesters, its ability to quash mass uprisings is not guaranteed.

If essential goods approach hyperinflation levels, even the security forces and loyalist cadres—who rely on fixed incomes—could begin to waver.

Israeli attacks in Gaza killed hundreds of people and took fire from Yemen's Houthis after US airstrikes on the group, shattering a relative calm with the Iran-backed groups as the standoff over Tehran's festers.

Israel launched air strikes on the battered coastal enclave on Monday killing over 400 people according to the Hamas-run health ministry, appearing to end a two-month ceasefire brokered by the United States.

The strikes on some 80 targets aimed at Hamas mid-level and senior personnel and were over in about 10 minutes, an Israeli security official said according to an official press release.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu accused Hamas of intransigence as talks for it to release 59 hostages seized in the Oct. 7, 2023 attack on Israel - many of them dead - floundered.

Iran's foreign ministry spokesman Esmaeil Baghaei blamed the United States for the attack, saying it had direct responsibility for "the continuation of genocide in the occupied Palestinian territories".

Hours later, the Israeli military said it intercepted a ballistic missile fired from Yemen, shooting it down beyond Israel's borders.

Meanwhile, the US Central Command announced it had carried out fresh air raids on the armed Houthi movement in Yemen allied to Tehran, publishing videos on X showing fighter jets taking off from an aircraft carrier.

The ceasefire in Gaza had tamped down 15 months of conflict pitting Iran and its proxies against Israel throughout the region which saw Iran's so-called "Axis of Resistance" much degraded, with Hamas and Lebanese Hezbollah heavily hit.

Looming behind the uptick of violence, Iran has so far defied a demand by US President Donald Trump to come to a new deal over its disputed nuclear program or face a military intervention.

According to an official White House readout of a phone call between Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday, "the two leaders shared the view that Iran should never be in a position to destroy Israel."

"The leaders spoke broadly about the Middle East as a region of potential cooperation to prevent future conflicts," the White House added. "They further discussed the need to stop proliferation of strategic weapons and will engage with others to ensure the broadest possible application."

The remarks suggest a fresh US bid to end the war in Ukraine may see Russia attempt to head off a conflict between its Iranian ally and the United States.

Tehran denies seeking nuclear weapons and top Iranian officials have vowed a devastating response to any attack.

US airstrikes hit dozens of Houthi targets throughout Yemen on Saturday in a bid to halt the Shi'ite armed groups attacks on commercial shipping and its own naval vessels, which have ensnared US sailors in the most intense fighting since World War II.

Yemen's Houthi foreign minister said the group will not halt its Red Sea attacks on shipping in solidarity with the Palestinians, saying Iran did not dictate its actions.

Trump on Monday warned the United States would punish Iran for any further attacks by the Houthis, which would be treated as emanating from the Islamic Republic itself.

Iran's military said its manned fighter aircraft had chased away an armed American attack drone in the skies off the Iranian coast, state media reported on Tuesday. There was no immediate reaction by the US armed forces.

The Pentagon on Monday indicated it did not seek an open-ended campaign in Yemen nor did it seek regime change, in an apparent reference to Iran.

“We will use overwhelming lethal force until we achieve our objective. And this is a very important point, this is not an endless offensive," spokesman Sean Parnell said.

"This is not about regime change in the Middle East, this is about protecting American interests.”

US president Donald Trump has sent Iran’s leader a letter, we’re told, and that it’s significant. It probably is, but nobody I know seems to think so.

"They keep saying Iran is at a crossroads. Is it really a crossroads if it drags on for years? Because we’ve been here as far as I can remember.” This is Zahra, 36, a legal consultant, almost snapping at me for bringing up this conversation.

"Trump has apparently told Khamenei to make a deal or get ready for war,” she carries on venting. “But I think he’ll dodge this one too, selling out even more to China and Russia, buying time, hanging in there at the so-called crossroads while we sink deeper in the swamp that he’s made.”

Zahra has stopped waiting for a turning point. And she’s not alone. Utter the words breakthrough in a Tehran taxi and you’ll get a bitter smile, if not a scornful look. Why talk or even think about it. As Zahra puts it, "it'll come when it comes."

For years, the government has pinned almost everything on sanctions—runaway inflation, energy shortages, environmental disasters, a failing healthcare system, you name it.

But many have long stopped buying that narrative. They’ve watched billions vanish in case after case of corruption, most involving officials and cronies that somehow always avoid justice.

"I cannot care less about sanctions,” says Mehdi, a salesman turned Snapp driver. “My children suffer with or without sanctions. And the officials’ children thrive with or without sanctions.”

Mehdi is 45, a father of two. His apathy may not help his country’s situation, he says, but at least it helps keep him sane. “I have to have my hands on this fifteen hours a day, six days a week, to make ends meet,” he says, bashing the steering wheel, “so I have no time for love-hate letters between Trump and Khamenei.”

Khamenei’s famous line—neither war nor negotiations—has defined Iran’s foreign policy for years. His recent remarks follow the same logic.

Many in Tehran believe this anti-talks position is why the face of Iranian diplomacy abroad, former foreign minister Javad Zarif, had to resign his role as vice president.

Zarif and his boss, president Masoud Pezeshkian, are clearly in favor of dialogue with the Trump administration, which puts them at odds with Khamenei even if they express their full allegiance at every turn.

Despite widespread apathy, many voted for Pezeshkian because they felt his moderate politics would increase the likelihood of a thaw with the West and potentially less sanctions that could improve their dire economic fortunes.

“If sanctions are lifted, foreign investment will return, and jobs will be created,” says Milad, a 20-year-old undergraduate and a first-time voter for Pezeshkian who sees himself in the minority.

“Most people I know prefer no talks, not because they back Khamenei, but because they hate his guts and think a thaw would help him last longer,” Milad adds. “I think they’re wrong though. Khamenei & co. would do just fine. It’s us who’ll shoulder Trump's maximum pressure.”

Milad thinks talks could potentially lead to less sanctions and improved life. But not many share his view, as he said. That flicker of hope that drove some people to polling stations last year is well and truly dead now.

Majid, a 28-year old street vendor, sums it up succinctly.

"My family was poor when oil money was pouring in, and we’re poor now with the harshest sanctions. We all work 50-60 hours a week just to survive. I can’t see how we’d get out of this."

The Islamic Republic has tied its survival to our destruction. Moderates or hardliners in government, during talks or at war, our suffering is constant," he added.

Majid’s grandfather, Akbar, interjects. He’s sitting on a stool next to his grandson to kill time, in his words.

“We’re screwed either way. So better not to have talks, I say. Any money would just fatten the bandits and thugs that rule us.” And Trump’s letter and ultimatum? “I don’t like bullies,” Akbar says smiling. “But we’re where we are because of Khamenei, not Trump.”

The grandfather may also be in the minority—of those who still follow the news religiously despite grudges. For a majority, as far as I can tell, Trump’s letter, Khamenei’s speeches, the latest threats and ultimatums barely register anymore.

People are exhausted. The news of war or negotiation causes only a brief ripple in the economic mire in which most people are trapped.

And the real question for most is, how much longer can we endure this?

Iran’s key reservoirs are reaching dangerously low levels as years of declining rainfall and heavy reliance on hydropower take their toll, a senior water official warned.

Isa Bozorgzadeh, spokesman for Iran’s water industry, said on Tuesday that the usable capacity of Karaj Dam near Tehran has dropped to nearly half, much of it rendered useless due to sediment buildup.

“Lar Dam has practically dried up, and Latian, Taleqan, and Mamloo reservoirs are facing a 46% decrease in rainfall compared to the average and 25% compared to last year,” he told ILNA news agency.

Water shortages have triggered growing concerns in recent weeks, particularly in Tehran and Isfahan provinces, where officials have raised the possibility of rationing.

Bozorgzadeh cautioned that Tehran is consuming 50 million cubic meters of surface water each month while the combined reserves of the capital’s five main dams—including dead storage and sediment—amount to just 60 million cubic meters.

“Conditions have deteriorated to the point where even a motorcyclist could drive through the reservoirs,” he said.

Eastern Tehran’s water and wastewater company reported that Latian and Mamloo dams are each only 12% full, while Lar is down to just 1%. Karaj, a historically stable reservoir, has shrunk to 7% capacity.

Iran’s water supply depends largely on rainfall, snowmelt, and underground aquifers, but decades of over-extraction have left groundwater tables severely depleted. The sharp decline in precipitation—down more than 40% in Tehran province relative to long-term averages—has compounded the problem.

Beyond Tehran, Bozorgzadeh identified Hormozgan, Sistan and Baluchestan, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, and Bushehr as regions struggling with a 50% drop in rainfall.

Government spokeswoman Fatemeh Mohajerani acknowledged the severity of the situation, saying, “A nationwide decrease in average rainfall this year has led to shortfalls as high as 75% in some provinces.”

Iran’s energy ministry reports show that despite lower rainfall, hydropower generation increased by 24% in the fiscal year beginning March 2023, amid the country's energy crisis, reaching 17 terawatt-hours and maintaining that level into the current year.

Dalga Khatinoglu, an oil and gas analyst, suggested the government’s decision to sustain hydroelectric output was a factor in the current crisis.

“Iran failed to achieve its planned growth in thermal and renewable energy, leaving it dependent on hydropower,” he told Iran International. “Over the past two years, the country commissioned just 4 gigawatts of new plants—about 30% of its target—with 90% being gas-fired. The rest came from renewables.”

Hydropower reliance, combined with a persistent drought, has accelerated reservoir depletion, leaving little room for recovery even if precipitation levels were to improve.

Meanwhile, Iranian media has begun to raise alarms about broader implications. Etemad newspaper warned that 2025 could mark a turning point in the country’s water and energy crisis, predicting that shortages could become more severe than any previously experienced. Some hydrologists have cautioned that Iran has used up nearly 1,000 years' worth of groundwater reserves in just three decades.