Related Articles

One thing unchanged by the return of UN sanctions is Tehran’s internal discord, with hardliners and moderates battling it out over decisions ultimately taken elsewhere.

Responses to the so-called snapback range from combative to despairing: hardliners celebrating, reformists urging more diplomacy and maverick parliamentarians calling for withdrawal from the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty or even building nuclear weapons. Amidst it all, the government appears adrift.

President Masoud Pezeshkian on Monday blamed Iran’s predicament on European states that activated the trigger mechanism, calling them “filthy and mean” without even attempting to lay out what he thinks lies ahead.

“They want us to surrender,” the president told a group of firefighters in Tehran. As for the response, “people have to resist.”

Other officials have responded with angry calls to withdraw from the NPT, ignoring the fact that exiting the treaty would further convince a skeptical West that Tehran’s self-styled peaceful nuclear program is veering toward weaponization.

Even more alarming are calls from parliamentarians and others to build nuclear weapons.

‘We should compromise’

Amid this flurry of reactionary rhetoric, sociologist Taghi Azad Armaki stood out with a different message.

“Iran should say that it is not standing against the rest of the world and that it is not going to fight the world,” he told moderate daily Etemad on Monday. “We should say that we are … ready to compromise,” Armaki added.

“The government is unable to say that, but civil society can … We should be part of the world, and not allow the world to unite against us.”

Armaki’s heartfelt pleas recall a Persian tale in which mice resolve to put a bell on a cat, only to admit none knew how—or dared— to do it.

Tall order

The only person who can end Tehran's confrontation with the West is the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. Iran's ultimate decision-maker can instruct Pezeshkian to stop calling world leaders “filthy” and engage.

Since the vote last Friday, France and the UK have stressed that the snapback of UN sanctions should not mark the end of dialogue. But Iran’s current posture suggests that its temper may take time to cool and that incentives may be needed to bring it back to the table.

And that won’t be easy given hardliners' staunch opposition.

“Iran’s return to the negotiating table will not happen easily,” conservative politician Mohammad Hassan Asafari told Nameh News on Monday.

Among the many suggestions for Iran’s next move, Jomhouri Eslami editor Massih Mohajeri and Ham Mihan proprietor Gholamhossein Karbaschi noted that state TV and hardliners appear jubilant over the snapback.

Elephant in the room

Sociologist Armaki urged the government to limit hardliners’ airtime—ignoring, like almost every other voice in Tehran, the elephant in the room.

Ultimately, all decisions in Iran hinge on one man, who decided to air his views against talks with Washington hours before Pezeshkian landed in New York.

Moderate analyst Hadi Alami Fariman came close to addressing the core issue on Monday, but fell short.

“Iran has to choose between tension and diplomacy,” Fariman told reformist outlet Rouydad24. “We will not get any result without reforms … in our political structure.”

That silence underscores the impasse: until the real seat of power acknowledges the need for change, Iran’s answer to sanctions will remain more bluster than strategy.

Pop concerts and late summer parties are spreading across Iran as music, as dance and fashion become battlegrounds testing the limits of state control.

Videos on social media show unveiled women dancing and singing freely at these events, some of them open to the public. In Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, models recently walked a red-carpet fashion show with no hijab in sight.

Just a few years ago, such scenes brought swift arrests. Most seem to meet no retaliation, and the fashion show earned only a limp judicial summons.

Some view these as proof of state retreat under social pressure. Others say it’s not real change but fleeting gestures to distract from economic hardship and the anniversary of the 2022–23 Woman, Life, Freedom protests in which hundreds were killed.

Hardliners fight on

Hardliners denounce hijab-free events as a betrayal of revolutionary values, warning that such openings erode ideological control and deepen rifts inside the establishment.

“It’s as if all the cultural officials of the country have perished together,” one conservative commentator posted online.

“Why did we have a revolution, sacrifice our loved ones to the enemy’s blade, and create a cemetery of martyrs? Only to become so like Westerners and allow a civilization … detached from Sharia to dominate us?”

At the Shah’s palace

The clash was visible at a September concert by pop star Sirvan Khosravi on the grounds of the Shah’s former palace, now run by Tehran Municipality. Clips of unveiled women singing and dancing went viral.

Only a year earlier, women were detained at another Khosravi concert for Islamic dress code violations. This time, police stood back. Some described the atmosphere as euphoric.

“Sirvan Khosravi’s concert was more than just a performance; it was walls breaking down,” said Nazanin, a 21-year-old student. “The compulsory hijab has nearly collapsed, and women are reclaiming cultural freedoms one by one.”

On X, a user named Mostafa used the hashtag #retreat: “Did anyone notice? The attendees sang ‘I love my life’ with no interference from enforcers … or police? The Mayor and City Council paid the costs, and police chief (Ahmadreza) Radan was busy protecting the dancers!”

Both officials had long promoted and enforced Islamic dress codes.

Opening or survival instinct?

Some among Tehran’s opposition accuse both artists and fans of playing into the establishment’s hands, saying that such events coincide with families mourning the third anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s killing.

“When certain groups in the government stage free street concerts during the protests’ anniversary, a wise person shouldn’t play on its turf,” one user posted on X. “Whatever the mullahs say and do, the opposite is right.”

Some see this tolerance as a survival tactic rather than real liberalization. Others believe it signals cracks in the Islamic Republic’s cultural order.

Music journalist Bahman Babazadeh argued: “The system has learned its lesson. It has moved beyond the stupidity of canceling concerts. It’s no big deal if a few reactionary zealots get angry by these images. For survival, the system has adapted.”

Filmmaker and academic Ali Azhari suggested the state tolerates “safe” cultural expressions while clamping down on those with social impact.

“The regime has concluded, more or less, that cultural mediocrity is harmless,” he wrote.

“Pop beats, commercial comedies with a few sexual jokes … don’t really pose a threat to the system. But when culture drives real social mobilization, there is no compromise.”

President Masoud Pezeshkian’s reference at the UN to Iranian children killed by Israeli strikes triggered a backlash at home, where many asked why he did not also acknowledge the dozens of children slain by Iranian security forces during the 2022 uprising.

The contrast revived one of the movement’s most searing slogans: “Death to the child-killing government.”

The stories of these children underscore the scale and cruelty of the crackdown, where even toddlers were killed and grieving families were threatened into silence.

The boy who became a symbol

Nine-year-old Kian Pourfalak from Izeh in southwest Iran became a national symbol. He was killed when security forces opened fire on his family’s car on 16 November 2022. His parents—wounded but survived—insist they were deliberately targeted.

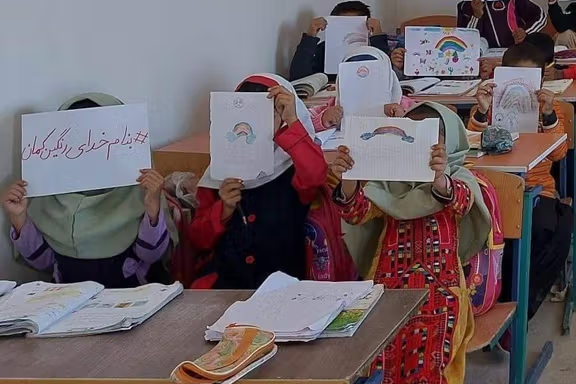

A bright, imaginative child, Kian loved rainbows and robotics, constantly inventing projects and experiments. One of his proudest creations was a boat built from lollipop sticks that floated successfully on water.

After his death, images of his rainbow drawings and handmade boat spread widely, becoming symbols of innocence and promise destroyed by the crackdown.

Kian’s parents have faced repeated intimidation and summons by intelligence officials for speaking publicly about his killing

The Youngest Victim

The youngest victim recorded was just two years old. Known only by her family name, Mirshekar, she was reportedly shot dead while playing outside her home in Zahedan, in southeastern Sistan and Baluchestan Province, on 30 September 2022.

That day—remembered as “Zahedan’s Bloody Friday”—was among the deadliest of the uprising.

Security forces and snipers opened fire on protesting crowds after Friday prayers in the city’s Sunni-majority area, killing over 100 people and injuring many more with live ammunition, pellets, and tear gas.

More than a dozen children were among the dead.

The Child Laborer

Also killed on Bloody Friday was Mohammad-Eghbal Nayeb-Zehi, a 16-year-old Baluchi boy.

From a poor family without official identity papers, he had worked in construction since the age of nine to help support his parents and siblings.

That Friday, he walked many kilometers from his village to Zahedan to attend prayers. Carrying just enough money for a sandwich afterward, he was gunned down.

His modest dream was to one day buy a smartphone and open an Instagram account—a simple ambition that captured both his hopes and the fragility of his life.

Lost Before First Class

Hasti Narouei, a seven-year-old about to begin her first year of school, never made it.

On 30 September, her grandmother took her along to Friday prayers. There, she was reportedly struck on the head by a tear gas canister.

Hasti suffocated and died before she ever had the chance to sit in a classroom.

Gunned down on the way to school

In a village near Saravan, also in Sistan and Baluchestan, Mona Naghib was walking to class with her older sister Maryam when security forces opened fire while chasing two teenage protesters.

A bullet struck Mona. Maryam tried to carry her home, but she died before any medical help could arrive. The family has faced threats from intelligence officials who ordered them to remain silent, according to rights groups.

Killed for chanting

Helen Ahmadi, a seven-year-old girl from Bukan in West Azerbaijan Province, was shot on 12 October 2022 while walking home from school with other children, allegedly for chanting slogans.

Activists say security forces later pressured her family to claim her death was caused by a car accident, highlighting the ongoing intimidation faced by families of children killed in the crackdown.

The reimposition of UN sanctions on Iran, atop the US sanctions President Masoud Pezeshkian had pledged to lift during his election campaign, has disillusioned many of his moderate supporters and prompted hardliners to call for his resignation.

Pezeshkian, who left New York on Saturday empty-handed after failing to secure a deal with European powers, said the United States demanded Iran surrender its stock of highly enriched uranium in exchange for only 90 days of relief from UN sanctions.

“If we are to choose between the unreasonable demands of the Americans and the snapback, our choice is the snapback,” Pezeshkian said, hours before the return of UN sanctions.

Kamran Matin, professor of international relations at the University of Sussex, told Iran International that Iran’s leaders knew negotiations would not succeed because halting enrichment and surrendering the highly enriched uranium stockpiles would have meant “total surrender”—something that would have endangered the Islamic Republic’ cohesion.

US-based commentator Ali Afshari argued that the responsibility went beyond Pezeshkian, stressing that presidents do not determine Iran’s strategic policies.

“Those who peddled illusions in the 2024 presidential ‘quasi-election’ cannot hold only Masoud Pezeshkian responsible for the return of UN sanctions and the war,” he wrote on X, adding that reformists had misled voters by urging participation.

Hardliners claim vindication

The snapback of UN sanctions has emboldened Pezeshkian’s conservative rivals who staunchly opposed the 2015 nuclear deal.

After the UN vote, his hardline election rival Saeed Jalili wrote on X: “In 2015 they said JCPOA would completely lift sanctions but almost nothing (happened). Ten years of a nation’s life was wasted because of this political behavior.”

Ultra-hardline lawmaker Amirhossein Sabeti, a close ally of Jalili, echoed his remarks: the JCPOA “was a colonial and one-sided agreement that wasted ten years of the nation’s life, restricted Iran’s nuclear infrastructure, and ultimately, by proving the wisdom of the revolutionary camp that opposed it from the beginning, exposed the illusions of the pro-West faction.”

On social media, ultra-hardline users demanded prosecutions. One wrote: “The end of the disgraceful JCPOA—the greatest shame in the history of Iran’s politics—congratulations to patriotic compatriots and those who care for Iran, and condolences to reformists, centrists, moderates, and all traitors to the homeland. It is time that those responsible for this disgraceful agreement be put on trial for this unforgivable betrayal.”

Some voices in the reformist camp lamented the collapse. Azar Mansouri, head of the Reform Front, accused conservatives of political score-settling.

“They fought it for years and now celebrate its death. But returning to the pre-JCPOA era means sanctions, isolation, and more pressure on the people. What is there to celebrate?”

Disillusionment with Pezeshkian

Frustration has increasingly turned toward the president. One user recalled his campaign pledge: “Pezeshkian had promised that if he failed to achieve his goals, including lifting sanctions, he would resign. Why didn’t he rely on popular mobilization to achieve his aims? Why doesn’t he resign now?”

Others mocked his unkept promises. “From the beginning, pinning hopes on Pezeshkian to lift sanctions was wishful thinking,” one activist wrote. “Someone who couldn’t deliver on his promise of lifting internet filtering after a year cannot be expected to deliver on lifting sanctions… He had also promised to resign if his pledges were not fulfilled.”

Journalist Mohammad Aghazadeh faulted reformists for urging turnout: “They frightened us by saying if Jalili won, the JCPOA would collapse, and war would break out. Pezeshkian was elected, but sanctions returned, and war came too—and will come again.”

Activist Hossein Razzagh, who boycotted the election, wrote: “The only thing Pezeshkian is not committed to is the votes of those he lured to the ballot box with promises of lifting the shadow of war. The only thing he is committed to is the Leader!”

Journalist Ahmad Zeidabadi urged Pezeshkian to level with voters: “Most of the decisive factors lie beyond his control. But he must frankly explain to the people what his plan is… In fact, he entered the second round of the presidential election with the aim of saving us from Saeed Jalili’s program. Now he is compelled to play Mr. Jalili’s role himself!”

Political activist Motahereh Gounei summed up the wider sense of betrayal: “You celebrated that Jalili didn’t come and Pezeshkian did! The country was ruined, its resources and infrastructure destroyed, we got both war and negotiations!"

"Sanctions returned, the dollar reached 110,000 tomans, and now I, a young Iranian, am awaiting a prison sentence simply for writing about Khamenei’s incompetence in governance and policymaking," the activist said.

Iran is sliding into stagflation that could spark unrest, economists warn, as official data reveal the first economic contraction in four years on the eve of the UN sanctions returning.

Several Iranian economists say the downturn is already entrenched and that officials are underestimating the severity of the crisis.

Tehran University professor Albert Boghozian argued last week that Iran now shows the classic symptoms of stagflation—negative growth, high inflation, and rising unemployment.

“Officials must not ignore the danger of deepening stagflation, which is likely to intensify if the snapback proposed by the UK, France, and Germany is implemented,” he cautioned.

The Statistical Center of Iran reported that GDP shrank by 0.1% in the spring.

Excluding the petroleum sector, the contraction deepened to -0.4%. Agriculture was the hardest hit, with output falling 2.7%. This downturn marks the first time since 2021 that Iran’s economy has posted negative quarterly growth.

'Worse to come’

The reversal is striking given the 3.0% expansion recorded in the last full calendar year ending March 2025. That period, supported by high oil revenues and relative stability, allowed for modest but steady growth.

Ali Ghanbari, a macroeconomist and former deputy agriculture minister, predicted conditions will deteriorate further in the coming months.

“Iran is heading toward a more difficult economic period in the second half of the Iranian year (September 2025 to March 2026),” he told reporters in Tehran.

He forecast a contraction of 1–2% by March 2026 and inflation climbing above 54%.

“The downturn had been anticipated due to sanctions and political tensions,” he added, “but the scale of inflation will place even greater strain on household budgets.”

Such levels of inflation would erode real incomes and fuel social discontent — a sensitive issue for the government as it braces for renewed sanctions.

‘Sanctions hinder development’

The Majles Research Center has argued that renewed UN sanctions would be less damaging than existing US restrictions, which already limit Iran’s access to global markets and financial channels.

But economists such as Boghozian believe Tehran has few tools left to cushion the blow.

“The Iranian government cannot do much about the UN sanctions,”he warned. “Continued stubbornness will only deepen the suffering.”

Sweeping UN sanctions are set to be reimposed on September 27 following the end of the 30-day snapback period.

Boghozian warned that their return could have consequences far beyond economic hardship, setting the scene for more confrontation with Iran’s foes.

“With the threat of war, Iran cannot realistically pursue development,” he said. “War and sanctions will rob the country of opportunities. If we fail to take initiative, the other side will dictate the terms.”