Iran shuts Instagram pages of several female singers over ‘criminal content’

Iranian authorities have shut down the Instagram pages belonging to several female singers in Iran’s Mazandaran province over the past few days, according to local media.

Iranian authorities have shut down the Instagram pages belonging to several female singers in Iran’s Mazandaran province over the past few days, according to local media.

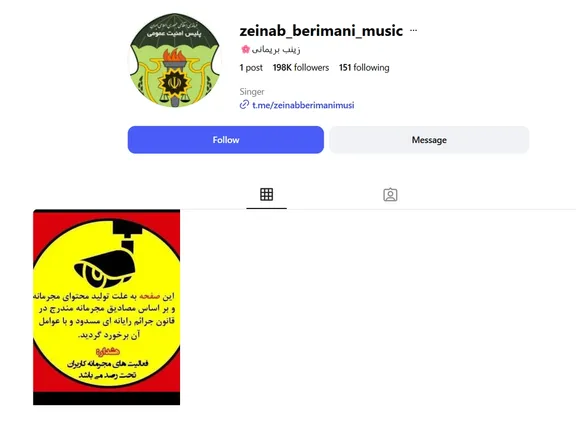

The accounts of Mandana Akbarzadeh, Azadeh Kebriya, Zeinab Berimani, and Fatereh Hamidi have been taken offline, displaying a message that reads: “This page has been blocked due to the production of criminal content."

The message displayed in the closed pages also says: "Warning: Users’ criminal activities are being monitored.”

The crackdown comes as part of a broader effort to limit the visibility of women vocalists, whose performances have been banned in public settings since the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The Islamic Republic has banned women from singing or dancing in public and enforces the Islamic veil or hijab on women.

Despite the official ban, female singers in Iran continue to find ways to share their music—whether in private gatherings, underground performances, or online.

One such artist, Zara Esmaeili, gained widespread attention last year when a video of her singing Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black went viral. However, shortly after the video gained traction in July, Esmaeili was arrested on August 1.

The restrictions on female artists have escalated since the protests following Mahsa Amini’s death in custody in 2022 over hijab, as many female performers supported the demonstrations. Several have been arrested or barred from professional activities.

Artistic defiance has become a hallmark of Iran’s protest movements, with musicians such as Shervin Hajipour, Mehdi Yarrahi, Saman Yasin, and Toomaj Salehi facing arrest for their roles in mobilizing dissent.

Bootleg and counterfeit alcoholic drinks are the leading cause of deaths from poisoning in Iran, the Legal Medicine Organization announced on Saturday.

Alcohol accounted for about five percent of all poisoning fatalities in the first five months of the current Iranian year, identifying illicitly produced drinks as the main source, said the Organization. It recorded 4,232 deaths from various types of poisoning during the period and noted a slight decline in alcohol-related fatalities compared with last year, when they made up six percent of the total.

Alcohol intoxication, according to hospital data, accounted for ten percent of poisoning-related admissions last year, falling to 8.5 percent in the first half of this year. Deputy Health Minister Alireza Raeisi said on October 11 that the actual number of alcohol poisoning cases was likely “ten times higher than those reaching emergency units.”

Alcohol ban and black market trade

The sale and consumption of alcohol have been banned in Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, with production, purchase, or use punishable by imprisonment, flogging, or fines. Repeat offenders can face the death penalty.

Despite strict penalties, demand for alcohol has persisted, driving a widespread underground market. Bootleg drinks, often made with toxic industrial methanol, continue to claim lives each year across the country.

Public health experts warn that the recurring poisonings underscore a growing social divide between state restrictions and personal behavior. Many Iranians view the persistence of black-market alcohol as evidence of resistance to religious regulation over private life.

The deaths caused by bootleg alcohol, the Legal Medicine Organization said, remain preventable through public education, early medical response, and stronger oversight of illegal production and distribution networks.

Iran’s hardline daily Kayhan, run by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s representative, blamed government bodies for lax enforcement of hijab rules and called for stronger promotion of compulsory veiling in a commentary published on Saturday.

The call came after remarks earlier this week by government spokesperson Fatemeh Mohajerani, who said “hijab cannot be restored to society by force” and that social values should be strengthened through cultural engagement rather than coercion.

“The enemy pretending to care about our women only dreams of removing their headscarves and seeing them naked, with no concern for their real needs,” Kayhan wrote.

The hardline paper argued that the establishment of the Islamic Revolution had “dispelled the illusion that unveiling represents progress or that hijab hinders development and talent.”

The paper portrayed unveiled women as targets of foreign plots and accused senior officials of “passivity and lack of cultural planning.” It said government institutions had failed to act decisively against the promotion of indecency by celebrities and online platforms.

“Purposeful norm-breaking now requires deterrent measures against those leading and promoting it,” the commentary said. “If Iranian women were properly informed, many would consciously choose the Islamic-Iranian lifestyle over Western models.”

It urged cultural bodies to include pro-hijab themes in school curricula, films, and television dramas.

Cultural pressure meets official restraint

Kayhan’s remarks came as Tehran’s Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice headquarters announced plans to deploy 80,000 volunteers to monitor hijab compliance across the capital.

Since the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of morality police, widespread defiance of hijab laws has persisted, turning daily appearances of unveiled women in major cities into a visible act of civil disobedience despite recurring enforcement campaigns.

A court in the Iranian holy city of Qom sentenced a 26-year-old man to rewrite a religious book by hand as punishment for wearing shorts while skateboarding.

His father, a practicing attorney, said that officers had handcuffed his son and transferred him to the local police station, where he was held overnight, legal advocacy website Dadban reported on Thursday without providing their names.

The young man was released on bail during a preliminary investigation but a judge on Friday sentenced him to write out the whole text of the religious book “Thirty Minutes in the Afterlife” as part of his sentence.

The book is reportedly used to illustrate Islamic concepts of the afterlife, divine judgment and personal accountability, often drawing from Shi'ite religious teachings and narratives about the Day of Judgment.

“Wearing shorts is not a crime and cannot be considered as provoking public sentiment,” the father said. “I have filed a complaint against the police station and the prosecutor for their unlawful behavior.”

“Iranian law contains no provision criminalizing the wearing of shorts by men. The act also does not fall under articles of the Islamic Penal Code, which addresses public acts of immorality, and therefore cannot be legally classified as a crime,” Dadban reported.

Iran enforces Islamic dress codes primarily through mandatory hijab regulations for women and girls, while men are also expected to observe modesty standards, such as avoiding shorts and keeping their shoulders and knees covered — although there is no written law prescribing specific clothing rules for men.

Calls are growing across Iran’s film industry to end state censorship, with thirteen trade unions joining directors and screenwriters in demanding the abolition of film production permits and pre-production controls imposed by government bodies.

In a rare declaration Wednesday, the unions—representing cinematographers, actors, production designers, sound recordists, editors, photographers and makeup artists—backed a statement issued a day earlier by the Iranian Film Directors Association condemning state censors.

“There is no justification for the existence of the Film Production Permit Council in today’s Iranian society,” the directors said in their statement. “Filmmakers will no longer seek approval from a body that judges their way of thinking.”

According to the state-run ISNA news agency, they called on Deputy Culture Minister for Cinema Raed Faridzadeh to disband the council and said their representatives would no longer participate in its meetings.

They also proposed that all film industry unions be represented in the separate body that grants screening permits after a film’s completion.

The call was backed on Wednesday by representatives of all trades, who said reform was essential in a “system of censorship that begins before a film is even made.”

Underscoring the challenges, It Was Just an Accident by auteur director Jafar Panahi went from being filmed Iran in secret to avoid censorship to a 2025 Oscar contender nominated by France, whose cinema industry participated in production.

Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and affiliated institutions such as the Farabi Cinema Foundation have exercised tight control over filmmaking—from script development and casting to posters and promotion—dictating even which actors’ images may appear in advertising.

Writers join in

On Wednesday, the Screenwriters Association joined the protest with a statement even more direct than the directors’ declaration.

Calling screenwriters “the first victims of censorship in Iranian cinema,” the group called for replacing the current system with a registration process that would not scrutinize content, allowing films to reflect life in contemporary Iran.

The screenwriters also urged the creation of a joint committee between the state and trade unions to rewrite filmmaking regulations and replace restrictive mechanisms with supportive frameworks.

Despite international acclaim for Iranian cinema, many filmmakers have been forced to work abroad to escape ideological controls, and some have faced prison upon returning home.

In March 2026, four Iranian films are expected to compete for the Academy Award for Best International Feature. Only one—Cause of Death: Unknown by Ali Zarnegar—represents the Islamic Republic.

The other three—It Was Just an Accident, The Things You Kill by Alireza Khatami, and Black Rabbit, White Rabbit by Shahram Mokri—have been nominated by France, Canada, and Tajikistan.

Iran’s government spokesperson said on Tuesday that the administration does not believe coercion can restore compliance with Iran’s hijab laws, amid renewed debate over enforcement and the deployment of tens of thousands of volunteers in Tehran.

Speaking at her weekly press briefing, Fatemeh Mohajerani said, “Hijab cannot be restored to society by force... The president has repeatedly said that we certainly cannot bring hijab back to people through coercion.”

She added that the government respects all existing laws but emphasized that social norms should be upheld through cultural engagement rather than force.

Mohajerani added that the government seeks to prevent the hijab debate from deepening social divisions.

“We must ensure,” she said, “that defending social values does not come at the cost of dividing our people.”

“We are a Muslim society,” she pointed out. “We must take care not to create divisions. While we believe inappropriate public behavior should be addressed, it is something that requires the cooperation of all citizens.”

Her remarks came after Tehran’s Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice headquarters said this month that 80,000 trained volunteers would be deployed across the capital as part of a new “hijab and chastity situation room.”

The initiative, announced by conservative officials, will rely on local monitoring and cooperation with cyber police and prosecutors.

No extra budget for hijab enforcement

Mohajerani also denied that any dedicated funding had been assigned for the recently announced mobilization, saying that “no special budget has been allocated for such programs.”

She added that Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) -- headed by the president -- remained the ultimate authority on matters related to social order and security.

The new hijab enforcement drive has drawn concern among reformist politicians and clerics who warn that policing public behavior risks further division.

Cleric Abdolkarim Behjatpour, a senior member of Iran’s Institute for Islamic Culture and Thought, told ILNA news agency this week that if the campaign “turns into arrests and imprisonment, it will harm the system.”

He said moral guidance “must be delivered politely, with compassion and dignity, not through enforcement that creates social rifts.”

Another senior cleric and member of the Society of Seminary Teachers in Qom, Mohsen Faghihi, said on Tuesday that “inviting people to observe hijab should not involve confrontation, morality patrols, or imprisonment,” warning that such measures only create tension and division.

However, Abbas Ka'bi, a senior cleric and member of Iran’s Assembly of Experts, warned earlier this week against what he described as neglect over hijab enforcement, calling it a religious and legal duty of all state institutions.

He described hijab as an asset "protecting Iran’s Islamic identity from Western moral decline," and urged coordinated, well-planned action by cultural, security, and judicial bodies to prevent what he called the spread of immorality.

Since the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of Iran’s morality police, enforcing compulsory hijab has become increasingly difficult, and the state’s ability to impose the rules has sharply eroded, particularly in major cities.

Since then, many women have continued to appear unveiled in public despite warnings, fines, and the return of hijab patrol vans, turning defiance into a daily act of resistance.

In recent months, however, authorities have revived enforcement drives through mobile patrol vans, increased fines, and business closures targeting cafés and shops accused of noncompliance.

Judiciary spokesman Ali-Asghar Jahangir said earlier this month that hijab laws remain in force, though enforcement methods have shifted toward targeting businesses rather than individuals.