Iran Executes Kurdish Political Prisoner Despite Public Appeals

The Islamic Republic has executed Heydar Qorbani, a Kurdish political prisoner Sunday after appeals by the public and rights organizations failed to save his life.

The Islamic Republic has executed Heydar Qorbani, a Kurdish political prisoner Sunday after appeals by the public and rights organizations failed to save his life.

According to Kurdisatn province justice department, Qorbani was executed at dawn on December 19, in Sanandaj prison after years of contention between human rights activists and Iran’s hardline Judiciary.

Qorbani had been arrested back in October 2016 after several members of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) were killed close to his hometown, the small city of Kamyaran.

Among the charges laid against him were the murder of three IRGC members and "taking up arms against the state" through membership in the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI), an armed opposition group. During his trial, he had rejected any connection with any political party, carrying arms, and involvement in the killings.

The government has intensified arrests and disappearances of Kurdish citizens and activists in recent months.

In 2018, the Iranian state-run Press TV aired by Qorbani for being an accessory to murder, and late in 2019, he was given the death sentence as well as a total of 90 years in jail plus 200 lashes.

However, according to his lawyer and Amnesty International his tainted confessions were obtained under torture, and he was not given a fair trial.

The 70-year-old mother of a blogger who was allegedly tortured and died in prison in 2012 has accused Iran's state television of faking a video to discredit her.

In a video posted to social media last week, Gohar Eshghi said she was pushed over steel bars on the side of a street by two motorcyclists as she was going to her son's grave. With large bruises under her eyes and a bandaged forehead, Eshghi said one of the motorcyclists dismounted, pushed her, and she passed out: "When I came to, I was in hospital."

A week later, on December 16, Iranian state television aired a video, which it said was from close-circuit cameras (CCTV), showing a woman resembling Eshghi from behind, swaying, staggering, and falling over the steel bars. No motorcyclists were in sight, but passers-by rushed to help, and called an ambulance.

The television program, 20:30, also interviewed the ambulance driver, and witnesses who said they saw Eshghi faint and fall.

"They are lying,” Eshghi told New York-based rights activist Masih Alinejad on Instagram following the TV program. “Why didn't they [show footage] from these cameras the first day? Why didn't they check their security cameras when my Sattar was killed to find my son's murderer?"

Some posts on social media claim the quality of the images suggests they were taken by “a professional camera” and not CCTV.

Eshghi, who holds Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei responsible for her son Sattar’s death, has set up a foundation in her son's memory that she says she had been under pressure to shut down. She was detained for five days in June.

Eshghi's 35-year-old son, Sattar Beheshti, a laborer, was arrested by police in 2012 due to his blog, My Life for My Iran, and social media posts. Beheshti's last blog post published a day before his arrest was a critical letter addressed to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei in which he called Iran's Judiciary "a slaughterhouse" that aimed to terrorize the Iranian people into submission and silence. He also claimed he had been threatened by “intelligence bodies”to shut his “big mouth.”

Charged with security offences, he died in detention a few days after his arrest, and after he had submitted a signed complaint that he had been tortured.

A postmortem identified the cause of his death as internal bleeding. Beheshti was buried by security forces in his hometown of Robat Karim, about 30 km from Tehran. Authorities denied allegations of torture and attributed his death to "natural causes", but 41 political prisoners at Evin prison signed a letter claiming his injuries had resulted from “hanging from the ceiling and severe beating.”

A top Judiciary official in Iran has defended the death penalty for minors, saying it is neither illegal nor against any of Iran’s international commitments.

The Secretary of Iran's High Council for Human Rights, Kazem Gharibabadi, made the remarks in reaction to a recent human rights resolution passed by United Nations General Assembly condemning the "alarmingly frequent" use of capital punishment, including against juvenile offenders, torture, and arbitrary arrests in Iran.

Gharibabadi, a former ambassador to international organizations in Vienna, said the executions of juveniles do not violate human rights, underlining that there is no compulsory international law prohibiting the practice.

Although no official data about the number of Iranian children in death row is publicly available, the UN has criticized Iran as one of the most prolific executioner of juveniles in the world, with some reports putting the numbers at about 100 a year on average.

“There are currently over 85 juvenile offenders on death row in Iran, sentenced to death following processes that significantly violate international human rights law. The majority of those sentenced to death are from marginalized groups or are individuals who themselves have been victims of abuse”, read part of a November statement by the Office of the High Commissioner for UN Human Rights.

UN human rights experts issued the statement to condemn the execution of Arman Abdolali, who was convicted for an alleged murder committed when he was 17. Arman was executed at dawn on November 24 after being transferred to solitary confinement the previous evening.

While the death penalty is not officially banned by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) or virtually any other universal treaty, there are several instruments in force to push states to abolish capital punishment, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a Washington-based non-profit organization that focuses on disseminating studies and reports on the capital punishment.

The ICCPR -- one of the three international treaties collectively referred to as the International Bill of Human Rights — mandates that the death penalty “shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age.”

In most countries a minor is defined as a person under the age of majority – generally 18 -- which legally demarcates childhood from adulthood. Adulthood in the Islamic law (or Sharia) is the time when someone reaches puberty or maturity. According to Sharia, people are considered innocent before that and don’t have full responsibility and Islamic law is not applied to them. However, the concept of minor is not clearly defined and differs based on the interpretation of different Islamic jurists.

An Iranian human rights group says rights defenders in Iran in 2021 received a total of 479 years in prison and were subjected to a host of inhumane treatments.

Human Rights in Iran, based in New York, in a report issued on December 16, titled ‘100 Iran Human Rights Defenders 2021’, has provided updates on the status of 100 human and civil rights defenders who are either in prison, released on bail or were subjected to harassment by authorities. Those who were convicted this year received a total of 479 years in prison and 907 lashes.

In every case, the accused were tried without due process of law, being either denied a lawyer or forced to accept government-approved attorneys, without full access to case material.

Iran Human Rights Director, Mahmood Amiry-Moghaddam said: “The world must not be a silent witness to the high price Iranian human rights defenders are paying for fundamental rights.”

Human rights defenders, activists and families of victims who received sentences or were subjected to harassment and intimidation doubled in 2021, the report says. The 100 people profiled in the report are “lawyers, journalists, teachers, women’s, workers and civil rights activists, environmentalists, minorities and whistleblowers.”

Iran slammed a critical human rights resolution passed by United Nations General Assembly Thursday, accusing Canada and the United States worse of violations.

Speaking to reporters, Kazem Gharibabadi, secretary of Iran's High Council for Human Rights, said the resolution was "full of baseless claims" while human rights were extensively violated in Western countries.

He cited Canada, the countrythat drafted the resolution, which was co-sponsored by Israel and the United States. The discovery of mass unmarked graves of 1,200 indigenous children in Canada has highlighted the state’s forced separation from parents of 150,000 children from mid-19th century to 1980.

The resolution adopted by UNGA Thursday, 78-31 with 69 abstentions, expressed serious concern at the "alarmingly frequent" use of the death penalty, including against juvenile offenders, torture, and arbitrary arrests in Iran.

It highlighted "torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment," which it said might include sexual violence as well as serious restrictions of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, and arbitrary arrests.

Gharibabadi, who is also the judiciary’s international relations deputy, said Iran's laws on torture were stricter than the UN Convention Against Torture. Iran is not a signatory to the UN convention, although Canada is.

Gharibabadi said that the Iranian legal system offered the chance of redress. "We have said repeatedly, anyone who claims to have been tortured should take their case to the authorities designated by the judiciary and the High Council for Human Rights and we will seriously follow it up," he said.

Although Iran often cites violations in Western countries as an indirect way to defend itself,

The resolution adopted by UNGA Thursday expressed serious concern at the "alarmingly frequent" use of the death penalty, including against juvenile offenders, torture, and arbitrary arrests in Iran. Human rights organizations and United Nations experts have called on Iran to end executions, especially those of juvenile offenders such as Arman Abdolali who was executed November 24 murdering his girlfriend when he was under 18. Iran has had the second highest rate number of death-penalty executions in the world, after China.

The resolution also urged Iran to release anyone detained solely over peaceful protests, and called for an end to “reprisals” against “human rights defenders,” protesters and their families, journalists, and individuals who cooperated with the United Nations “human rights mechanisms."

Twenty-three rights groups including international organizations recently said the “international community” should urge Iran to free activists detained “arbitrarily” including three arrested in Augustwhile planning to sue Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.

Iran’s delegate to the UN, Zahra Ershadi, in November said Canada’s resolution exposed a "deliberate policy of incitement to Iranophobia,” violated the UN "principles of non-selectivity and impartiality," and undermined cooperation and dialogue on human rights.

Ershadi said the resolution's co-sponsors − the US, Israel which she called “the child killer Israeli regime,” and Canada − were the "main proponents of racism, occupation, and abhorrent treatment of indigenous peoples." The sponsors were scoring political points by instrumentalizing human rights, she said.

Although Iran often cites violations in Western countries as an indirect way to defend itself, the issue is that there is little recourse for victims in Iran, while citizens can openly seek redress through independent courts in Western countries. There is also tight control over media in Iran and intimidation of journalists that make publication of news about violations difficult.

The growth of social media in recent years has helped expose many violations in Iran.

Lawdan Bazargan whose brother was executed as a political prisoner in Iran in 1988, argues that a diplomat who defended prison killings should not teach in a US college.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Opinion

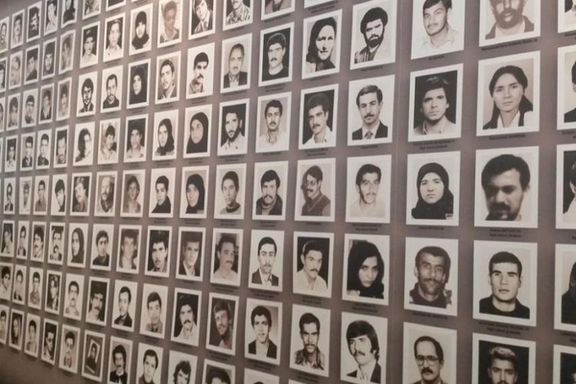

It's been 33 years, and I still don't know where my brother is buried: and I am not the only one. The families of thousands of victims of the 1988 prison massacre in Iran have never received so much as an acknowledgment from the regime that it ever happened. Moreover, one of the top diplomats from that time, who was covering up the crime, now flourishes as a professor at a top American college. The school has so far refused to hold him accountable. Americans committed to human rights should refuse to be silent. It's time Mohammad Jafar Mahallati, the so-called peace professor at Oberlin College, answer for his crimes.

When the Iranian Revolution happened in 1979, my brother Bijan was a college student in London. He was a brilliant man with his whole life ahead of him. At the same time, Mahallati—now a professor at Oberlin College in Ohio—studied in a college in the United States. Despite my parents' pleas, Bijan returned home soon after the revolution to help rebuild his homeland. He joined one of the country's leftist parties challenging the oppressive Islamic regime that weaponized religion to suppress dissident voices and was soon arrested, jailed, and tortured for years without an indictment.

Meanwhile, Mahallati returned to Iran too and climbed the political ladder. He was named spokesman for the Islamic Republic of Iran's Foreign Ministry, preaching the virtue of Islamic values and becoming one of the faces of the Islamic regime's brutality.

Bijan eventually received a 10-year prison sentence for being a member and supporter of a leftist party. Though he suffered extreme physical and psychological abuse in prison, going on a hunger strike with fellow detainees to demand better conditions, and being denied badly needed care for a medical condition, my family and I maintained hope that we would someday reunite.

That all changed in the summer of 1988, six years and three months into his sentence, when Bijan and thousands of other political prisoners were executed by the Iranian government based on a Fatwa (Islamic Decree) issued by Ruhollah Khomeini, the Supreme Leader. Bijan was buried in an unmarked mass grave. The year prior, while my brother unjustly languished in prison, Mahallati was promoted to Iranian ambassador to the United Nations. Amnesty International estimates that 5,000 political prisoners were murdered in the summer of '88 extrajudicial killings.

For the past 12 years, as a religion professor at Oberlin College, Mahallati has been helping shape the minds of American students. But the fact remainsthat by November 1988, the regime Mahallati represented at the UN was partly denying and partly justifying the executions. And despite a resolution by the UN General Assembly that expressed "grave concern" about "a renewed wave of executions in the period July-September 1988," Mahallati, in his official capacity, said the resolution was based on "fake information."

Political dissidents in Iran remain under threat of unlawful imprisonment or death, yet the eyes of the world stay closed to their struggle. As Iranian freedom of speech activist and blogger Hossein Ronaghi recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal, "For us, it is as if there are two Irans—the one where we live and another that you read about. Your Iran is defined by a pesky nuclear negotiation. Ours is much worse. It is a religious police state where we live in fear, with countless red lines that most dare not cross. It is a country of repression, censorship, and violence."

This isn't a story about so-called "cancel culture" or free speech on college campuses: this is about human rights as a beacon of hope and applying a standard of treatment to all people, no matter where they're born. In a letter to Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar on October 8, 2020, which still remains unanswered, I joined other family members of those killed by the government Mahallati represented, “We want Mahallati removed from his post, we want an apology, and we want to know how someone with Mahallati's past could rise to prominence at such a prestigious institution.”

I cannot sit idly by while Mahallati preaches peace when he's done so much to disrupt it. When I went to the Oberlin campus the first week of November, I hoped the administration would meet with family members of the victims and me on behalf of Bijan and thousands of others who gave their lives for a better world. Unfortunately, the administration decided to ignore us once again.

As an Iranian-American, I have long watched the human rights abuses back home viewed as a sideshow to broader international policy fights. But most difficult of all has been watching Americans who say they're committed to protecting human rights ignore the Iranian people's suffering—past and present. Human right is not a leftist issue or a conservative issue; it is the moral rod that should guide us all.

Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily the views of Iran International.