Related Articles

Remarks by a senior adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader warning of Iran being pushed to produce nuclear weapons by US threats have sparked intense debate in Iran.

In a televised interview on Monday, Ali Larijani suggested that if Iran were attacked and public demand for nuclear weapons emerged, even the Supreme Leader’s religious decree (fatwa) against weapons of mass destruction could be reconsidered. Nonetheless, he insisted that Iran is not pursuing nuclear arms and remains committed to cooperating with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Khamenei’s ruling was presented by Iranian officials at the International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament in April 2010. But such religious decrees could be altered or overturned given the ‘requirement of time and place’ as many historical instances prove.

Many hardliners and ultra-hardliners in Tehran—typically staunch critics of the moderate conservative Larijani—have embraced his remarks on social media.

“Had any other political figure raised the possibility of the Islamic Republic moving toward nuclear weapons, they would have been accused of warmongering or bluffing. Dr. Larijani’s decision to bring it up was a wise move and a timely act of sacrifice,” wrote Vahid Yaminpour, a prominent ultra-hardliner and former state television executive, on X.

“The Iranian nation wants nuclear weapons,” declared Seyed Komail, an ultra-hardliner social media activist with 27,000 followers, in response to Larijani’s remarks.

Abdollah Ganji, former editor of the IRGC-linked Javan newspaper, dismissed concerns over potential US or Israeli strikes, arguing that Iran’s nuclear facilities are too deeply fortified to be destroyed. He warned that an attack could lead to Iran's withdrawal from the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and retaliation against US military bases and Israel.

However, Larijani’s remarks stand in contrast to official government positions. Soon after his interview, Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi reaffirmed on X that Iran “under no circumstances” would seek, develop, or acquire nuclear weapons, emphasizing that diplomacy remains the best course of action.

Nour News, an online outlet believed to be affiliated with Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), also weighed in, questioning whether the US is prepared to face the consequences of further escalation.

Larijani’s statements have drawn strong criticism as well. Detractors argue that such rhetoric provides the US and Israel with an excuse to justify pre-emptive military action. “The Leader’s fatwa prohibiting nuclear weapons is absolute and without exceptions,” posted cleric Saeed Ebrahimi on X, adding that raising the prospect of nuclear bombs would only give Iran's enemies justification for aggression.

Mohammad Rahbari, a prominent political commentator in Tehran, suggested that Larijani’s remarks signaled Iran may be alarmingly close to nuclear capability—precisely the kind of pretext Israel has been seeking for a preemptive strike. Senior reformist journalist Mohammad Sahafi also warned that such nuclear posturing could alienate potential allies who might otherwise support Iran in the face of Western pressure.

“Larijani's comment was unprofessional and came from a position of weakness; it had no merit. It also gave the other side an excuse to have strong reasons for pre-emptive action and to shape a global consensus. In short, if we are concerned about our homeland, we should not take such a reckless stance,” Hemmat Imani, an international relations researcher in Iran, wrote.

Others speculate that Larijani’s remarks are part of ongoing indirect negotiations with Washington. “Ali Larijani’s ‘warning’ should be seen as a calculated move in high-level negotiations,” suggested Iranian environmental journalist Sina Jahani.

Describing Larijani’s remarks as “a form of nuclear blackmail the Islamic Republic has used as a tool of threat for years,” Arvand Amir-Khosravi, a Norway-based academic and monarchist, wrote on X that the threat was “nothing more than a propaganda ploy to gain leverage in potential negotiations,” adding that pursuing nuclear weapons would invite military retaliation rather than enhance Iran’s security.

The United States Office of the Director of National Intelligence reported in November 2024 that, as of September 26, Iran was not actively building a nuclear weapon. However, last month, Rafael Grossi, director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), described Iran’s nuclear program as extremely ambitious and wide-ranging. He warned that the country's uranium enrichment had reached near weapons-grade levels and was alarmingly close to the threshold for acquiring nuclear weapons.

US President Donald Trump has threatened to bomb Iran and impose secondary tariffs if Tehran refuses to reach an agreement with Washington on abandoning its nuclear ambitions and making other concessions.

While the Trump administration has previously used tariff hikes as leverage against nations it regarded as rivals, this approach has little impact on Iran, which exported only $6.2 million worth of goods to the US last year and just $2.2 million in 2023.

However, secondary tariffs could pose a serious threat to Iran. Under this mechanism, the US could target countries that import sanctioned Iranian goods by imposing tariffs on their exports to the American market.

This is particularly significant given that, according to Iranian customs data, about 83% of Iran’s non-oil exports go to seven countries: China, Iraq, the UAE, Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. With the exception of Afghanistan, all have substantial trade ties with the US. Continued commerce with Iran could jeopardize their access to the American market.

This issue presents two major challenges for Iran. First, it threatens the country’s ability to export sanctioned goods—such as oil, petrochemicals, and metals—to key markets. Second, it disrupts Iran’s strategy of using trade partners to rebrand these goods and reroute them to third countries.

In the first 11 months of the last Iranian fiscal year, which ended on March 20, Iran exported $43 billion worth of goods to these seven key countries. Meanwhile, according to the US Census Bureau, those same countries exported over $550 billion worth of goods to the United States in 2024—more than 11 times the value of their imports from Iran.

Take China, for example. Iranian customs data show it imported around $13.8 billion in non-oil goods from Iran during that period. In addition, tanker tracking data indicate that China received approximately 1.5 million barrels per day of Iranian crude and fuel oil--worth an estimated $40 billion.

Although China benefits from steep discounts on Iranian petroleum and non-oil goods, it exported $427 billion worth of goods to the US last year--highlighting the potential cost of secondary tariffs.

Rebranding Iranian products

The gap between Iran’s official trade figures and those reported by its key trading partners suggests that a substantial share of Iranian exports is being rebranded and re-exported as if originating from those countries.

For example, Iranian customs recorded $13.8 billion in non-oil exports to China over the first 11 months of the last fiscal year, yet China’s Customs data show only $4.44 billion in non-oil imports from Iran for all of 2024. Similarly, Iran reported $6.4 billion in exports to Turkey, but Turkish data—including natural gas—registered just $2.45 billion in imports from Iran. The discrepancy persists with India: Iranian data show $1.8 billion in exports, while India’s Ministry of Commerce reported only $718 million in imports from Iran.

Iraq, the UAE, Pakistan, and Afghanistan do not publish detailed trade statistics. However, Iran's reliance on countries like the UAE for rebranding sanctioned goods and rerouting them to global markets appears highly likely.

As noted, Iran’s foreign trade is concentrated in a small group of countries. This concentration means that imposing US tariffs on those re-exporting Iranian sanctioned goods would not be especially difficult.

Another key point is that US sanctions extend well beyond crude oil. They also target Iranian exports of petroleum products (such as liquefied petroleum gas, or LPG), petrochemicals, metals, and more. These items make up the majority of Iran’s non-oil exports.

In the first 11 months of the last fiscal year, Iran exported over $10 billion in LPG, $13 billion in petrochemicals, $10 billion in metals (especially steel, aluminum, and copper), and $5 billion in gas. These four categories alone accounted for 70% of Iran’s non-oil exports, with nearly all shipments headed to the seven countries mentioned above.

The back-and-forth between Iranian and US leaders over Tehran’s nuclear program and the prospect of negotiations has changed little since at least 2016.

That was when US author and scholar Ray Takeyh published his book Hidden Iran: Paradox and Power in the Islamic Republic. According to Takeyh, since 1979, “getting Iran wrong is the single thread that has linked American administrations of all political persuasions.”

On January 31, 2006, “President George W. Bush described Iran as a nation held hostage by a small clerical elite that is isolating and repressing its people,” and warned that, “The nations of the world must not permit the Iranian regime to gain nuclear weapons.” That sounds all too familiar, doesn’t it?

According to Iran’s official news agency, as quoted by Takeyh, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad responded swiftly and defiantly, denouncing Bush as someone "whose arms are smeared up to the elbow in the blood of other nations," and threatening: "God willing, we shall drag you to trial in the near future at the courts set up by nations."

That was 19 years ago, when Khamenei was still a relatively restrained Supreme Leader, delegating much of the incendiary rhetoric to his firebrand president. In 2025, he presides over a timid president who adds little to the official line — a line that is always dictated by Khamenei himself. In fact, Iran's rhetoric toward the current US President is notably more restrained.

Yet, as many observers have noted over the past 46 years, Iran and the United States have a tendency to address each other at the wrong times and in the wrong ways. Bush’s labeling of Iran as part of the "axis of evil" was just one moment that derailed budding cooperation in Iraq and Afghanistan and sent both sides back into confrontation — a dynamic that persists to this day.

In last week’s exchange between Washington and Tehran over Iran’s nuclear program, Trump delivered bold and harsh remarks on live television — remarks that Khamenei denounced as "bullying." But Trump also sent more conciliatory messages, according to his Middle East envoy, Steve Witkoff, in a private letter to the Supreme Leader.

Given Khamenei’s well-known sensitivities, he might have better tolerated the harsh language in a private message and possibly even welcomed the friendlier overtures had they been made in public.

Similarly, Tehran’s responses over the past week — starting with a flat rejection of negotiations, moving to an openness to "indirect talks," and concluding with a vague “for the time being” — send a clear signal to US diplomats: Iranian officials are not interested in a public handshake with their American counterparts. Especially not after Khamenei has already set the tone with stern, uncompromising statements.

By contrast, Trump appears to want exactly that public moment — a warm handshake in front of cameras — to distinguish himself from his predecessors. This mismatch in the style and optics of diplomacy makes it difficult for either side to envision a path out of the current impasse.

As with traditional bargaining in Persian bazaars, Iranian negotiators prefer drawn-out talks, complete with repeated withdrawals from and returns to a draft agreement — all to eventually close the deal at the very moment when observers begin to believe it's off the table for good.

What’s different today is that some of those observers — both in the region and beyond — may not want a deal at all, at least not one that allows any form of nuclear capability to survive. For countries like Israel and Saudi Arabia, a weak agreement that merely delays the threat is less acceptable than no deal at all. They would rather see Iran’s nuclear ambitions completely capped than postponed.

President Donald Trump has made one point clear: he is determined to prevent Iran from becoming a nuclear weapons power. However, he has yet to outline the specific conditions or steps he would require from Tehran to achieve that objective.

Will he demand a complete halt to uranium enrichment, or permit Iran to purify uranium to a low level, such as 3.65%? The JCPOA, signed during the Obama administration, set that exact limit.

Enrichment and centrifuges

Tehran is now rapidly enriching uranium to 60%, having accumulated 274.8 kilograms (605.8 pounds) of uranium enriched up to 60% as of February 26. That’s an increase of 92.5 kilograms (203.9 pounds) since the IAEA’s last report in November. The current stockpile can easily be sufficient for further enrichment to produce six nuclear bombs.

Iran maintains that it has the right to enrich uranium as part of its civilian nuclear ambitions. While 3.65% enrichment is used for peaceful energy purposes, 60% has no credible civilian application and is just one step short of weapons-grade enrichment at 90%.

A closely related issue is the number and type of enrichment machines—Iran’s centrifuges. Under the JCPOA, Iran was limited to 6,104 first-generation centrifuges, with no use of advanced models. Today, it operates more than 8,000 centrifuges, including more advanced IR-6 machines, which were explicitly banned under the deal.

Key questions remain unanswered: How many centrifuges, if any, would the US allow Iran to keep? Would decommissioned machines be permitted to stay in the country under international monitoring? Would Washington demand that most, if not all, be dismantled? Could it ask Iran to transfer them to a third country, such as Russia?

These questions are central to understanding what Trump’s plan might be for denying Iran a path to nuclear weapons. So far, no clear answers have emerged.

Is Trump’s plan a total nuclear ban or verification?

If talks resume and the US agrees to let Iran retain some enrichment capacity, a new agreement may not look so different from the JCPOA that Trump abandoned in 2018, calling it a “bad deal.” The key distinction, however, could lie in permanence: a new deal might cap Iran’s enrichment capabilities indefinitely, unlike the JCPOA’s temporary restrictions under sunset clauses.

Still, there is at least a political difference between a permanent ban on all enrichment and formally recognizing Iran’s right to enrich—however limited that right may be.

There is also the issue of somewhat differing statements coming from the President and some of his top officials. According to Axios, Trump’s letter to Ali Khamenei included a two-month deadline for reaching a new nuclear agreement and warned of consequences if Iran expanded its nuclear program. The letter was described by sources as “tough” in tone.

However, Trump’s Middle East envoy, Steve Witkoff, framed the message differently in an interview released Friday on The Tucker Carlson Show. Referring to the letter, he said: “It roughly said, I'm a president of peace. That's what I want. There's no reason for us to do this militarily. We should talk. We should clear up the misconceptions. We should create a verification program so that nobody worries about weaponization of your nuclear material.”

This tone stands in stark contrast to statements by the Secretary of State and the National Security Advisor, who have called for the dismantling of Iran’s nuclear program—not just verification.

Multilateral or bilateral talks?

The Obama administration, building on the approach of the Bush era, dealt with Iran in coordination with European allies while also involving Russia and China in the JCPOA negotiations. This multilateral strategy gave international legitimacy to the pressure on Tehran and, for a time, resulted in UN-imposed economic sanctions—until the 2015 agreement was signed and sanctions were subsequently lifted.

However, this approach also gave Iran some room to maneuver, as China and Russia provided support during the JCPOA negotiations. The temporary nature of the agreement and its allowance for Iran to retain its uranium enrichment capability may have stemmed from the fact that the US was not only negotiating with Tehran but also balancing the interests of Beijing and Moscow.

The question now is whether the Trump administration will face pressure to once again include Russia and China in any future talks—or whether it will insist on negotiating directly with Tehran, without outside involvement.

Iran held consultations with Russia and China earlier this month and would certainly prefer to have diplomatic backing in a multilateral setting.

Both Russia and China have signaled that any negotiations should focus solely on Iran’s nuclear program, excluding other US demands such as restrictions on ballistic missiles or curbing regional influence. Iran will almost certainly seek to involve both powers—especially Russia—believing that President Vladimir Putin may hold some sway with Trump.

Although bilateral talks may be preferable from the US perspective, the reality remains that if Washington seeks UN endorsement for any future agreement, it will need the backing of both Russia and China.

Another JCPOA?

Although the Trump administration has issued an ultimatum of “negotiations or else” to Tehran, it remains unclear whether it intends to impose strict demands for dismantling key elements of Iran’s nuclear program or enter into bargaining over critical issues such as the right to uranium enrichment, the level of enrichment, and the number and type of centrifuges.

In the latter case, and if Iran is able to salvage its right to enrichment, the resulting agreement will be somewhat similar to the 2015 JCPOA.

Iran began its new fiscal year on March 21 amid deepening economic and energy crises, with even officials of the Islamic Republic acknowledging that conditions are likely to worsen in the year ahead.

Meanwhile, the return of Donald Trump to the White House and the revival of the US administration’s maximum pressure policy have further tightened the noose on Iran’s economy.

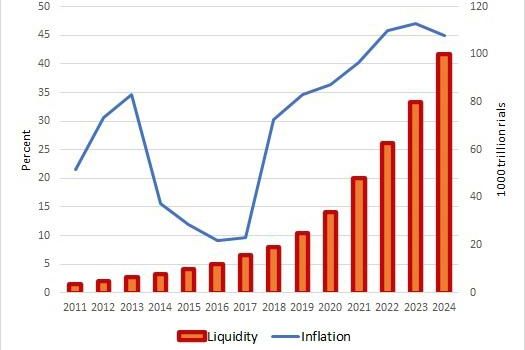

While the Central Bank reported a year-on-year inflation rate of 45% last month, local media suggest that actual price increases are far higher. In reality, the cost of food, medicine, and other essential goods has nearly doubled.

Moreover, the fiscal year is ended with the US dollar surging to nearly 1 million Iranian rials, marking a 65% increase since the beginning of the past fiscal year. The depreciation of the rial has accelerated sharply in recent days.

At the same time, Central Bank data reveals that Iran’s foreign reserves have been rapidly depleting, plunging to just one-fourth of their level in March 2024 and a mere tenth of their March 2023 levels.

Iran’s foreign trade situation:

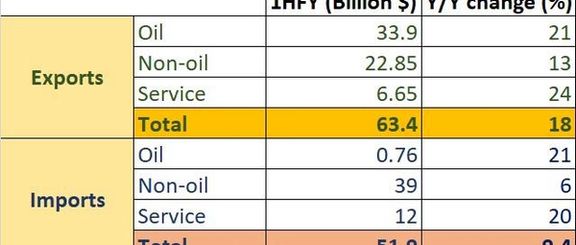

The latest figures from the Central Bank show that Iran's foreign exchange revenue crisis persisted in the first half of the current fiscal year, which began on March 20, 2024. No data has yet been released for the second half of the year.

During this period, Iran recorded a positive overall trade balance of $11.5 billion, including oil, goods, and services. However, the country also experienced capital flight totaling $12.5 billion.

As a result, the net balance of foreign currency inflows and outflows—including gold bullion—turned negative.

Given the sharp decline in Iran’s oil exports to China since September, the situation is expected to worsen—particularly as oil, petroleum products, and natural gas account for more than half of the country’s total exports.

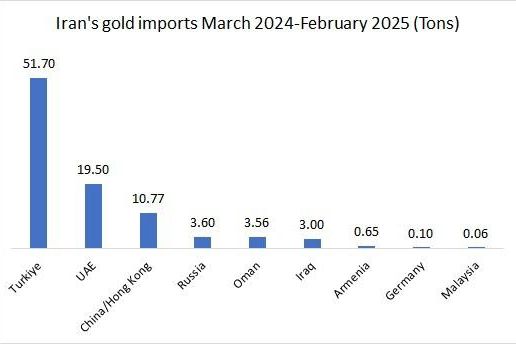

Over the first 11 months, Iran has imported approximately 93 tons of gold bullion worth $7.3 billion in exchange for its oil and goods exports—three times the amount imported in the previous year. More than 55% of this gold was purchased from Turkey.

Indeed, around 13% of Iran’s total oil and non-oil exports have been bartered for gold instead of foreign currency. This highlights the government’s inability to collect payments for exported goods and oil and transfer foreign currency into the country, due to US banking sanctions. As a result, Iran is facing a severe shortage of foreign exchange reserves.

Government debt crisis

Recent data from the Central Bank shows that the Iranian government’s debt to the banking system has surged by 41% during the current fiscal year. To cover its widening budget deficit, the government has relied heavily on borrowing from domestic banks, tapping into the National Development Fund, and issuing bonds.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Iran’s total government debt now exceeds $120 billion—roughly one-third of the country’s economy. In contrast, Iran’s total external debt, including both governmental and non-governmental liabilities, stands at less than $10 billion—just 2% of GDP—underscoring the country’s extreme financial isolation and the reluctance of international institutions to fund Iranian projects.

Two decades ago, before the imposition of heavy sanctions, Iran’s external debt was more than 12% of GDP, largely driven by foreign investment in oil and gas projects. Today, the government’s increasing dependence on domestic borrowing has sharply boosted liquidity, further fueling inflation. Over the past year alone, liquidity in Iran has risen by 28%.

The economic crisis has pushed more Iranians into poverty. Official reports suggest that one-third of the population lives in extreme poverty. However, based on the World Bank’s global poverty standards, around 80% of Iranian households earn less than $600 per month and fall below the poverty line.

Energy and Water Crisis

For the first time, Iran has experienced electricity and gas shortages across all seasons. During peak summer demand in 2024, electricity shortages reached 20%, while winter gas shortfalls surged to 25%. Officials warn that energy shortages could worsen by at least 5% in the next fiscal year.

Industrial reports show that since summer 2024, energy disruptions have forced 30–40% of Iran’s industrial capacity to shut down. At the same time, the country has been grappling with growing gasoline and diesel shortages since 2023. Without new refinery projects, these fuel deficits are expected to escalate rapidly.

Meanwhile, Iran’s water crisis has reached a critical stage. Tehran’s main reservoirs are reportedly at just 7% capacity, and officials warn of severe water shortages by summer 2025.