Iran’s lithium reserves: Separating fact from fiction

A recent report from Iran’s Ministry of Industries, Mines, and Commerce has reignited misleading social media claims that Iran ranks among the top countries in lithium resources.

Iran International

A recent report from Iran’s Ministry of Industries, Mines, and Commerce has reignited misleading social media claims that Iran ranks among the top countries in lithium resources.

According to the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) linked Fars News Agency, the ministry reported high lithium concentrations in brine in Qom Salt Lake, Khor in Iran's Central Desert, and Tarud in Semnan Province.

Fars suggested that these findings could position Iran as a key player in the global lithium mining industry, although the scale of the discovered deposits pales in comparison to those controlled by the world's top ten lithium producers.

An official from the Presidential office’s Mines Working Group reported that with a lithium concentration of 60–70 ppm, this deposit would yield only 500–600 tons of lithium—far from the claim that Iran had discovered 20% of the world’s lithium.

The world’s major lithium reserves are found in the "Lithium Triangle" (Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile), while Australia leads in hard-rock lithium mining. The latest data ranks Bolivia as the top holder of lithium reserves, with an estimated 23 million tons. With usable reserves close to 14 million tons, the US ranks third in the world.

Due to security restrictions, Iranian government websites are inaccessible from outside Iran. However, Fars reported that the findings stem from a year-long study conducted in collaboration with Russian experts using advanced technologies such as ICP-OES. According to Fars, this study confirms the presence of lithium reserves with globally competitive concentrations.

The Fars report on March 12 has been widely republished by Iranian media and amplified on social media, especially by accounts linked to hardliners that claim Iran is on the brink of a "Green Lithium Revolution." Such claims are often used as a means to create optimism among the population as the country's economy continues to deteriorate.

This is not the first time that exaggerated claims about Iran’s lithium resources have circulated. In November 2024, a very well-known ultra-hardliner and vigilante, Hossein Allahkaram, said in an online debate that Iran held the fourth-largest reserves of lithium in the world, even suggesting that Elon Musk sought negotiations with Iran.

Similar misinformation spread in February 2023 when Iran’s official news agency IRNA quoted a ministry official, Ebrahim-Ali Molabeigi, claiming the discovery of 8.5 million tons of lithium in Hamedan Province.

Global excitement over the report faded after it was revealed to be a misinterpretation. The actual discovery was 8.5 million tons of hectorite clay containing lithium, not pure lithium reserves.

Lithium plays a crucial role in rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles, smartphones, laptops, and energy storage systems. While it is primarily extracted from salt lake brines and hard rock deposits, alternative sources such as clay deposits and geothermal brines are not yet widely used for commercial production.

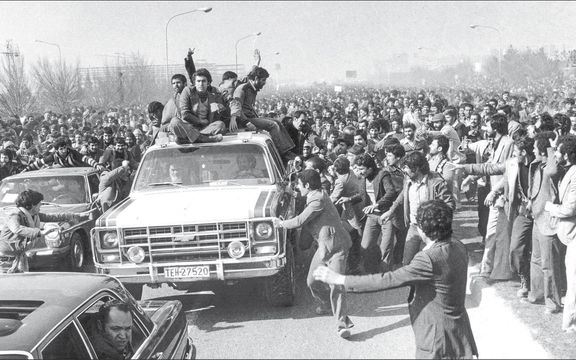

More than 40 years after the 1979 revolution and despite persistent tensions between Tehran and Washington, American cars remain a prized symbol of prestige and nostalgia in Iran.

Classic American cars, often spotted cruising the streets of Iranian cities, serve as moving relics of a bygone era. For many Iranians, these cars are more than just a means of transportation; they represent cultural heritage, status and a deep-rooted admiration for American engineering.

Even Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader - the man who led the 1979 revolution and coined the term Great Satan for the United States - was driven in an American car upon his return to Iran from exile.

The 1977 Chevy Blazer disappeared soon after that momentous day and was found and restored only in 2025.

Other prominent figures of the Islamic Republic have also been spotted riding American cars. Gholamali Haddad Adel, a former parliament speaker and a close relative of current leader Ali Khamenei, was often seen behind the wheel of a Chevrolet Caprice Classic in the 1990s.

Saeed Jalili, former chief nuclear negotiator and a hardline contender in the 2024 presidential election known for his staunch anti-US rhetoric frequently drove an Oldsmobile during his tenure at the Foreign Ministry’s watchdog bureau.

While Iran’s domestic auto industry spearheaded by Iran Khodro since the late 1950s has made strides in assembling European and Korean vehicles, American cars remain synonymous with distinction and exclusivity.

In a country where foreign imports are tightly restricted, owning a US-made vehicle is a luxury—an emblem of prestige often reserved for the elite.

'Good old days'

The appeal of American cars predates the 1979 revolution.

Three years previously the Iranian government launched the "Cadillac Iran" assembly line, producing nearly 2,500 Cadillac Seville luxury sedans. This venture blended local manufacturing with American craftsmanship, solidifying the place of US vehicles in Iranian automotive culture.

Popular Iranian car vlogger and enthusiast Alireza jokingly claims that being a true driver in Iran requires either a German luxury car or an American gas-guzzler.

“If you can’t afford a Mercedes, you can’t call yourself a driver unless you’re behind the wheel of an American V8,” he quips. He also shares a favorite saying among Iranian classic car lovers: “A man must drive a Chevy for work, a Buick for leisure and only a Cadillac for a rendezvous.”

The admiration for American cars, particularly those from the 1960s and 1970s, is rooted in their durability, reliability, and timeless design. While the revolution led to a strict ban on American imports, the restriction only intensified their appeal and elevated them to the status of coveted classics.

Much like Cuba where vintage car restoration has become a national pastime Iran has seen a growing demand for mechanics skilled in repairing and maintaining American cars.

29-year-old Tehran mechanic Farhad Keshavarz inherited his shop from his father, who specialized in these vehicles long before the revolution.

“These cars demand the highest level of care, and their owners can’t wait to show off their roaring engines,” says Farhad, who receives daily requests for full overhauls and engine restorations.

For over four decades, American V8s in Iran have transcended political divides, symbolizing status, power and a golden age of automotive excellence.

While many Americans now associate reliability with Japanese brands like Honda and Toyota, in Iran, "Made in America" still carries a mystique.

Here, an American car is not just a machine—it is a statement, a status symbol, and a cherished link to an era when luxury and power ruled the open road.

Protests over water shortages in central Iran escalated over the weekend after demonstrators set fire to a key water transfer station in Isfahan province, disrupting the supply line that channels water to hundreds of thousands of Iranians in the province of Yazd.

Footage received by Iran International shows smoke rising from the pumping station early Saturday, following a rally by farmers demanding access to Zayandeh Rud water — a long-promised resource they say has been diverted elsewhere.

“There’s been no release of water into the river despite repeated promises,” said one farmer at the protest, adding that local agriculture has been devastated by years of inaction.

Farmers in Isfahan have repeatedly accused the government of diverting their water to other provinces, particularly Yazd, while their own access to Zayandeh Rud — once the lifeblood of regional farming — remains restricted. The issue has sparked protests for years, often met with a heavy security response.

The disruption has triggered a major water emergency in Yazd, which is now facing what officials describe as red-level shortages for the population of well over half a million.

Mohammad-Javad Mahjoubi, head of Yazd’s regional water authority, said the pipeline was completely shut off after the attack and warned there was no estimate for when it might resume.

Jalal Alamdari, the managing director of Yazd’s water utility, described the situation as critical and confirmed that 13 mobile tankers had been deployed across the province.

Isfahan is considered one of the most critically affected provinces in Iran in terms of water scarcity, and the people of this region have repeatedly gathered and protested against the inefficient management of the Islamic Republic in addressing the issue.

In some cases, the protests have been met with repression by Iran's security forces. The first major act of sabotage on the pipeline occurred in 2012, tensions only intensifying since.

Interior Minister Eskandar Momeni acknowledged the broader crisis last week, calling water scarcity a “serious national issue” and urging citizens to cut back on usage.

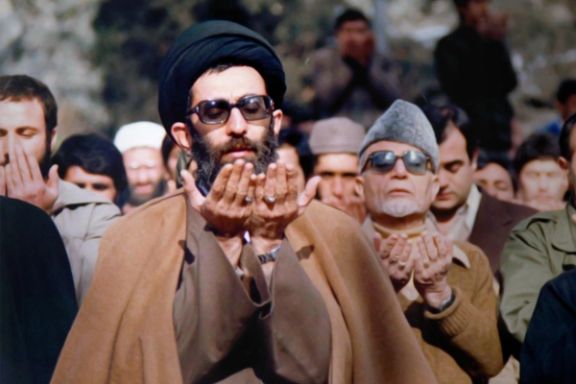

Many middle-aged and older Iranians associate Friday prayers with the iconic image of a cleric delivering a sermon four decades ago while holding a 1970s G3 assault rifle—once a symbol of revolutionary power and defiance.

In the 1980s, following Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic revolution and during the Iran-Iraq war, Friday prayers drew large crowds and held significant public appeal. Over time, however, attendance declined as the lineup of Friday prayer imams changed, and growing dissatisfaction with the Islamic Republic’s social restrictions and worsening economic conditions further eroded their popularity.

Today, Friday prayers resemble weekly political briefings, often attended by local military and civilian officials. Policy directives are routinely sent from Tehran to guide the content of the sermons, turning them into orchestrated political messaging platforms.

Since assuming power, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has restructured the Friday prayer apparatus, moving its coordinating headquarters from the religious center of Qom to Tehran. He also systematically removed the imams appointed by his predecessor, Ruhollah Khomeini, replacing them with younger clerics more aligned with his vision.

Facts and figures

According to an investigation by the Iran International website:

- There are currently 850 Friday prayer imams across Iran.

- Around 85% of them were appointed after 2017.

- Most cities have two Friday prayer imams.

- The seven-member Friday Prayer Headquarters under Khamenei’s control appoints imams even in small towns with populations as low as 500.

- About 70% of the imams appointed since 2017 have served with Iran’s military forces or were embedded with military units in Syria.

- Only one imam appointed by Khomeini remains in his position today.

Leading the Friday prayers is only one of the responsibilities of the Imams. They also lead the local councils in charge of imposing Islamic social and cultural control. They also supervise Islamic tax organizations, they are jury members at the Press Courts, they are member of the trustees of the Islamic Azad University, member of the Educational Council and local security councils among many other responsibilities. Some have their own bureaucratic empire.

Khamenei introduces changes

When Ali Khamenei became Supreme Leader, he replaced four of the seven members of the headquarters overseeing Friday prayer imams. Ten months later, he renamed the body the Policy-Making Headquarters for Friday Prayers. Significant changes followed the 2018 nationwide protests, when Khamenei appointed a younger cleric, Mohammad Haji Ali Akbari, as its head. Haji Ali Akbari also serves as one of Tehran’s Friday prayer imams.

Unlike most cities, Tehran does not have a permanent Friday prayer leader. In each of Iran’s 31 provinces, the Friday prayer imam also serves as Khamenei’s official representative.

Kazem Nour Mofidi, the Friday prayer imam of Golestan province, is currently the only one still in office from Khamenei’s earlier appointments. Historically, many provincial imams were members of the Assembly of Experts—the body responsible for selecting the Supreme Leader’s successor. Of those appointed after 2017, however, only six hold seats in the Assembly. Most of the older imams were replaced due to political misalignment with Khamenei’s views.

The province of Isfahan has the largest number of Friday prayers imams (86) while two provinces, Qom and Kordestan have 8 imams each.

The imams, who enjoy Khamenei’s backing, in many cases wield a lot of political power in their city, adjudicating differences among officials, overseeing local government decisions and in times of civil unrest rally government forces and supporters against protesters.

What is Friday Prayer?

Muslims face Mecca five times a day every day to say their prayers. Muslims may do their mid-day prayers in congregations of at least five individuals as "Friday prayers." The imams deliver two speeches called sermons before the prayers. Friday prayers are compulsory in Sunni populated areas which the Shiites may or may not turn up for the congregation.

Khomeini never led Friday prayers while Khamenei used to lead the prayers regularly in his early years as Supreme Leader. However, he has been only occasionally taking part in Friday prayers in recent years.

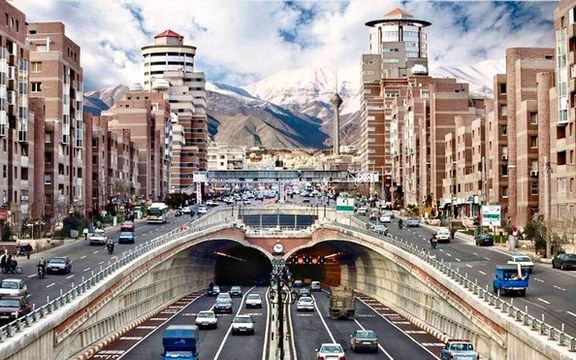

Recent tremors outside Tehran this month have underscored the threat of a catastrophic earthquake to the capital built on fault lines, adding to the dread of inhabitants also grappling with water shortages, power cuts, and pollution.

Two overnight earthquakes, measuring 3.0 and 3.3 in magnitude, struck Varamin—a densely populated and impoverished town southeast of Tehran—on March 14. While the tremors were felt in the southern parts of the capital, no casualties were reported.

Just a day before the incident, a member of Iran's International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology (IIEES) warned that Tehran was at greater risk than ever of experiencing a devastating earthquake.

Seismologist Fariborz Nateghollahi cautioned that a magnitude 7.0 earthquake could result in up to six million casualties. He also criticized the government’s crisis management efforts, highlighting the lack of preparedness and inadequate training for such a disaster.

Tehran’s seismic vulnerability

Greater Tehran, now home to over 10 million people, sits in a seismically active region with three major fault lines and many smaller ones.

A study conducted in collaboration with the Japan Cooperation Agency (JICA) a few years ago found that these fault lines have the potential to trigger earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or higher, potentially destroying up to half of the city's buildings.

Seismologists, including Nateghollahi, have repeatedly warned that based on historical seismic cycles, any of these fault lines could become active at any time soon.

A 2018 IIEES study estimated a 40–70% probability of a major earthquake within a 100-kilometer radius of central Tehran in the next two to 12 years.

The last major earthquake in what is now Greater Tehran occurred in 1830, with a magnitude of 7.1, striking Shemiran—a small village at the time. Over the past few decades, Shemiran has transformed into one of the capital’s most affluent districts, now filled with high-rises, government buildings, and shopping malls.

High-risk areas

The southeastern part of Tehran, also situated on a major fault line, is considered the city’s most vulnerable area. It is characterized by densely packed old buildings and narrow streets, which would severely hinder rescue operations in the event of a major earthquake.

Additionally, the region has suffered from land subsidence due to a drastic decline in underground water levels over the past few decades.

A capital under strain

Authorities say the 47 percent drop in rainfall in Tehran province, the worst in the past 57 years, has seriously depleted the water reserves of several dams that supply the city’s drinking water. Images published in recent weeks showed that Karaj dam, one of the largest, had almost completely dried up. The dams also contributed to electricity generation to feed the capital, which has been experiencing regular power cuts in the past few months.

Iranian authorities, including President Masoud Pezeshkian, have on various occasions spoken of the need to relocate the country's capital due to its extreme vulnerability to major earthquakes.

In recent years, a shortage of water resources, land subsidence due to a decline in underground water levels, and air pollution have also become serious threats to the survival of the capital, established in 1786.

A history of devastation

Iran is one of the most seismically active countries in the world, with approximately 575 identified fault lines. Earthquakes of varying intensity are common, often resulting in significant casualties and destruction.

In 1990, a 7.4 magnitude earthquake struck Manjil and Roudbar in the Caspian mountains, killing between 35,000 and 50,000 people. Thirteen years later, a 6.6 magnitude earthquake devastated the southeastern city of Bam, claiming at least 34,000 lives.

An unprecedented police crackdown on pro-hijab protesters in Iran suggests a shift in priorities, signaling that defiance of higher authorities even by supporters will no longer be tolerated.

On Friday evening, hundreds of male and female police officers raided a makeshift vigilante camp outside the Iranian parliament, dispersing around two dozen protesters—mostly women—who had been stationed there for over 45 days. They were protesting the delay in enforcing a controversial hijab law.

While no arrests were reported, religious vigilante groups claim that police used excessive force. They called on their supporters to rally outside the parliament on Saturday afternoon. A spokesman, Hossein Allahkaram, announced later that the rally would be postponed until after the Nowruz holidays.

Tehran’s deputy governor defended the crackdown on Saturday, warning that unauthorized rallies would not be tolerated.

In the past, security forces have even protected radical supporters during high-profile actions, such as the storming of the British embassy in 2011 and the Saudi embassy in 2016—both of which triggered major diplomatic crises.

A defiance of the Supreme Leader and his policy shift?

In mid-September, Iran's Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) suspended the implementation of the hijab legislation, which imposes harsh penalties—including heavy fines and prison sentences—on women who violate strict dress codes and businesses that fail to enforce them. The decision was reportedly driven by concerns over public backlash and the risk of triggering anti-government protests.

Since the decision could not have been made without the approval of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has avoided discussing the issue in his speeches for months, criticism of the delay could be viewed as defiance of what appears to be a strategic shift in Khamenei’s approach.

Vigilantes continue to refer to Khamenei’s April 2023 speech, in which he took a firm stance. Khamenei declared in the speech that disregarding hijab was “religiously and politically haram (forbidden).” In the same speech, he accused foreign intelligence agencies of encouraging Iranian women to defy the mandatory hijab. However, he has conspicuously avoided addressing the hijab issue in recent months, including during his December 17 address to an all-female audience.

Rather than blaming Khamenei, vigilantes hold Mohammad-Bagher Ghalibaf responsible for the delay in enforcing the legislation and argue that he should be accountable for Friday’s crackdown. Hours before the crackdown, they chanted against Ghalibaf during his speech at Friday prayers in Tehran.

The Friday crackdown could also be seen as a warning to ultra-hardliners that opposition to Khamenei’s potential policy shifts— possibly including allowing engagement in direct talks with the Trump administration—will not be tolerated.

“Consider the recent actions against [pro-] hijab protesters as marking a shift in Iran’s political landscape,” a former aide to ex-President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Abdolreza Davari, posted on X, suggesting that authorities are now seeking to mend their relationship with the hugely disillusioned middle classes.

Debate over freedom of assembly

The police action has sparked debate over the right to assembly in Iran. Some opposition figures have criticized the crackdown.

Ali-Asghar Shafeian, chief editor of the reformist Ensaf News, argued in a tweet that the police response was unnecessary and contradicted President Masoud Pezeshkian’s stance on freedom of expression.

Others, including prominent Islamic law expert Mohsen Borhani, pointed out that the vigilantes—who had no permit for their sit-in—have consistently rejected the right of other political groups to protest, despite Article 27 of the Iranian Constitution protecting peaceful assembly.

Internal rift among ultra-hardliners

Pro-hijab vigilante groups, often referred to as “super-revolutionaries” by rival hardliners, maintain strong ties with the ultra-hardline Paydari (Steadfastness) Party and its ally, Iran Morning Front (Jebhe-ye Sobh-e Iran), also known as MASAF. However, their insistence on enforcing the hijab law has even caused fractures within the Paydari Party itself.

Mahmoud Nabavian, a senior Paydari member who played a key role in drafting the hijab law, recently argued that the preservation of the Islamic Republic must take precedence over enforcing the law, given the multiple domestic and international crises that it is facing—implicitly acknowledging the risk of unrest.