Iran's Use Of Dirty Fuels Continues Despite End Of Cold Season

Some power plants in Iran are still using dirty fuel Mazut, even though the colder months associated with gas shortage are over, an Iranian lawmaker has said.

Some power plants in Iran are still using dirty fuel Mazut, even though the colder months associated with gas shortage are over, an Iranian lawmaker has said.

Iran grapples with a serious shortage of natural gas every winter and summer. Many industrial units, including gas power plants, are forced to switch to Mazut for fuel –a low quality, heavy oil that produces considerably higher amounts of pollutants.

This year, the shortage seems to have been prolonged, according to Hossein Ali Heji-Deligani, a member of Iran’s parliament (Majles) for the industrial region of Shahin Shahr in central Iran.

Haji-Deligani, a member of the Judicial Committee of Iran’ Majles, warned Monday that about 3 million people living in the vicinity of a power plant in his constituency are exposed to dangerous amounts of pollutants.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Mazut emits 33% more CO2 than natural gas. Iran’s Mazut contains 3.5% sulfur, almost seven times more than acceptable levels for ship fuel –which makes its use in urban areas highly problematic.

Iranian experts have been warning against using Mazut in place of natural gas for some time. But the shortage of natural gas has been severe enough in colder months to put down all environmental (and health) considerations.

In 2021, gas held about 71% share in Iran’s energy supply, according to the International Energy Agency, a 295% rise since 2000.

If that trend continues, experts have warned, Iran may face chronic shortages in the years to come, potentially making it more reliant on imports despite having the second largest natural gas reserves in the world.

Nearly three weeks after the parliamentary elections in Iran, disputes continue about the results and the way the elections were held, with 7,000 complaints received from just three towns.

Gholam-Ali Jafarzadeh Imanabadi, a former lawmaker from the northern city of Rasht, questioned why candidates with judicial clearance were rejected from running in the parliamentary election, while others caught in illegal activities were approved by the Guardian Council's arbitrary vetting process.

Imanabadi charged in an interview with Rouydad24 website that the biased vetting of the candidates has led to the formation of the weakest parliament in the Islamic Republic’s 45-year history, and the coming to power of the weakest President.

The Guardian Council is a constitutional body supposed to approve candidates to make sure their beliefs and conduct do not violate the basic tenets of Islamic laws. However, in recent years, the body controlled by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has become capricious, rejecting former senior regime officials and anyone whose complete loyalty is in any doubt.

Imanabadi also raised concerns about the consistency of the Guardian Council's decisions. When questioned about the rejection of former Majles Speaker Ali Larijani's qualification in the 2021 presidential election due to his daughter living abroad, contrasting with the approval of incumbent Majles Speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf despite his son's overseas residency, Guardian Council Spokesperson Tahan Nazif stated: "Every election has its own criteria. However, no candidate has ever been disqualified solely on the basis of his family's situation."

However, the Guardian Council had officially cited Larijani's daughter's residence abroad as the reason for his disqualification. Imanabadi noted that as Larijani's daughter is a married woman, her situation should not affect her father's eligibility. He further queried: "How can a man who has led the legislative body for 12 years lack qualifications?"

Meanwhile, referring to Ghalibaf's case and corruption charges against him, Imanabadi said that any other candidate with one fifth of the problems Ghalibaf has, would have never gotten through the Guardian Council's vetting. He added that there were other candidates who got through although had been convicted or were involved in unethical corruption cases.

He charged that the Guardian Council wants only ultraconservative "yes men" for the parliament. Imanabadi further said that the Guardian Council's decisions on qualifications is politically motivated.

Similar questions have also been raised about the Guardian Council's verdict about the Assembly of Experts candidates' disqualifications of senior politicians including former President Hassan Rouhani.

Rouhani's former chief of staff Mahmoud Vaezi said in an interview with the Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) on Monday that Rouhani was informed about his disqualification through a telephone call from the Guardian Council. Rouhani who is an incumbent member of the Assembly has repeatedly called for explanations for his disqualification, but the Guardian Council has left all of his inquiries unanswered.

Vaezi refuted the Guardian Council's claim about Rouhani's representative having been briefed on the reasons of his disqualification, adding that the former President has never sent a representative to the Guardian Council. He added that the claim about Rouhani's representative was made only after Rouhani sent four letters to the Council.

The complaints made by Rouhani is not the only ones sent to the Guardian Council. On Monday, the IRGC announced on Telegram that the Guardian Council has received more than 7,000 complaints about the elections just from the three cities.

The IRGC's Telegram channel explained that the complaints made from Andimeshk were about scaring the voters and election officials on the voting day, serious assault and battery against voters including women, fighting at polling stations, thugs preventing people from voting, attacks on private vehicles, throwing stones at people's houses, distorting ballot papers, and early victory announcements. However, the IRGC's Telegram channel did not elaborate on the outcome of those complaints.

In the western city of Hamedan in Iran, 35 retail businesses faced closure after being accused of disrespecting the holy month of Ramadan.

Mohammad Arghavan, head of the Hamedan Chamber, condemned individuals who encouraged others to break their fasts, labeling it as an “insult to the devout residents of Hamedan.”

Simultaneously, in the southern city of Dezful, authorities sealed 10 shops on Saturday for failing to observe the sanctity of Ramadan. Masoud Bahrampour, the Friday Prayer Imam of Dezful, used his sermons to criticize such disregard for religious observance, calling for strict penalties to deter further violations.

Iranians are required to refrain from eating, drinking, and smoking in public during Ramadan, even if inside their vehicles. Article 638 of Iran's Islamic Penal Code, implemented about 12 years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, mandates penalties ranging from 10 to 60 days imprisonment or up to 74 lashes for violating fasting regulations, applicable to all regardless of religion.

Traditionally, eateries including restaurants, cafes, and street vendors are prohibited from serving customers from dawn to sunset during Ramadan, limiting business hours exclusively to evenings. However, in recent years, some establishments have been permitted to offer cold food options or takeaway services during fasting hours.

The impact of Ramadan restrictions extends beyond the hospitality industry, affecting various businesses such as cinemas, concert halls, and beauty salons, either directly or indirectly.

Hopes for increased economic cooperation between Iran and Saudi Arabia following last year's diplomatic reconciliation have not materialized, due to historical and political factors

Saudi Arabia and Iran have a long history of hostility, usually taking opposing sides in regional conflicts such as Yemen, Lebanon, and Syria.

This competition, fueled by disruptive activities and outright attacks on Saudi land and oil infrastructure, strained relations in the last two decades. However, encouraged by China, the resumption of relations in 2023 presented the possibility of some cooperation between the two regional powers. However, despite this success, Saudi Arabia has opted not to engage in Iran's energy development initiatives, citing various reasons.

The Islamic regime in Iran has long sought political and military dominance in the region, angering Sunni Arab neighbors, with Saudi Arabia having the most to lose if Shia Iran establishes supremacy. This lies behind costly rivalries in Yemen and other parts of the region.

It was believed that following restoration of diplomatic relations, their economic ties would improve, notably in the oil sector. However, Saudi Arabia has made no investments in Iran, particularly in the energy sector, during the last year.

Iran has signaled a willingness to cooperate with Saudi Arabia on oil reserves, including the contentious Arash/Durra gas field in the Persian Gulf, off Kuwait’s coast. However, Iran's oil industry receives less investment than Saudi Arabia, and there are ongoing disagreements over the Arash/Durra field, which Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait all claim.

Saudi Arabia, which has historically relied on its massive oil reserves, is seeking to diversify its energy portfolio by investing in renewable energy projects outside of its borders. This includes substantial investments in the Caspian region and Central Asia, which have abundant energy resources but require investment and technological knowledge to fully realize their renewable energy potential.

These investments provide economic benefits for both Saudi Arabia and the host nations. They provide energy security, promote economic growth, and create jobs in the renewable energy sector. Furthermore, they support host nations' attempts to diversify their energy sources and minimize carbon emissions.

Divergent economic priorities serve as another barrier to collaboration. While Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 emphasizes diversification away from oil, Iran grapples with Western sanctions and economic challenges, struggling to generate significant revenue from its oil exports. This disparity in economic goals impacts potential cooperation in Iran's energy sector, especially as Saudi Arabia focuses on bolstering its domestic economy.

US sanctions on Iran influence Saudi decision-making in expanding economic ties, as most other countries and investors who have stayed away. Iran has attracted a negligible amount of foreign investments since the United States withdrew from the JCPOA nuclear deal in 2018 and imposed sanctions.

Differences in technological capabilities, operating norms, and infrastructural development between the two nations may provide obstacles to possible investment initiatives. Disparities in resource management methods and industry norms may need to be resolved before major expenditures can be made.

The longstanding dispute between Iran and Kuwait over the Dorra oil and gas field has revived, with Saudi Arabia and its Arab ally Kuwait refusing to acknowledge Iran's claim to 40% ownership of the resource. Saudi Arabia claimed in July 2023 that it and Kuwait had "full rights" to the whole region, which was enthusiastically supported by all six Gulf Arab monarchs at their most recent summit in December.

A vast gap between Iranian and Saudi political and economic visions, such as the difference in goals between Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 and Iran's fight against sanctions, provide further challenges.

These challenges are further compounded by disparities in technical and operational standards between the two countries, which need to be addressed before significant investments can be undertaken. Additionally, geopolitical interests play a crucial role, as both Saudi Arabia and Iran aim to reduce their dependence on oil. Saudi Arabia's strategy prioritizes diversification, potentially shifting its investment priorities away from Iran's oil sector. Likewise, Iran's endeavors to attract foreign investment may face competition from sectors or regions that align more closely with Saudi Arabia's geopolitical objectives, underscoring the complexities of engaging directly with Iran's oil assets.

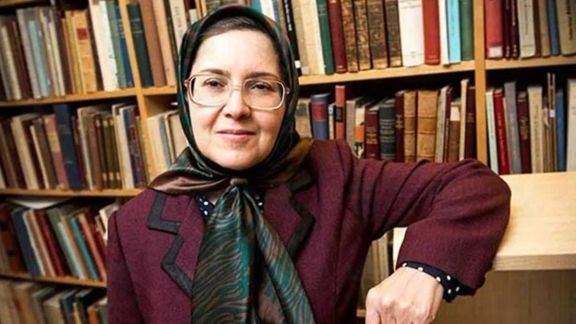

Sedigheh Vasmaghi, a prominent writer and Islamic scholar currently held in Tehran's notorious Evin prison, has refused a summons to appear before the Tehran Revolutionary Court branding it "illegal".

In response to the summons, Vasmaghi said, "The Revolutionary Court is not lawful, and defending oneself in this unjust court is meaningless. I will not appear there and I do not want to confront the unjust judges."

She was arrested on Saturday after her ongoing criticism of compulsory hijab laws and her characterization of Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, as a “dictator”, and the ruling regime as “oppressive”.

Vasmaghi's warrant levies accusations against her including "anti-government propaganda on social media" and "appearing in public without Islamic hijab". She has long been an advocate of women's rights. She first gained attention after she removed her own hijab in protest following the death of Armita Geravand, a teenager killed by hijab-enforcement agents in the Tehran metro last year.

Vasmaghi's family now fear for her health as she is deprived of access to adequate medical facilities. A source close to her family told Iran International that her health deteriorated on Monday morning in prison, with her heart rate exceeding 120 and her blood pressure rising above 160.

Evin prison authorities also denied Vasmaghi permission to meet her family on Sunday, citing her refusal to wear a headscarf and comply with mandatory hijab rules.

The Tehran Province Court of Appeals has upheld the five-year sentence for Saeed Azizi, an Iranian-Swedish dual-national, one of several held as part of Tehran's hostage diplomacy policy.

Azizi, 60, was arrested by Iranian security forces on November 12 at his private residence shortly after returning from Sweden to Iran. His lawyer had previously highlighted Azizi's deteriorating health condition, citing prostate cancer and injuries sustained from a fall in prison.

The case of Azizi adds to a series of detentions involving dual-national citizens in Iran. Notably, Ahmadreza Djalali, an Iranian-Swedish physician and researcher arrested in 2016, and Johan Floderus, a Swedish diplomat working for the European Union detained in April 2022, have also faced accusations of espionage.

The Swedish government has expressed deep concern over the detention of its citizens, demanding their immediate release. In mid-January, Sweden called for Azizi's release, stating that Iran had detained him "without any specific reason."

Critics accuse the Islamic Republic of Iran of leveraging the detention and trial of Western or dual-national citizens as a means to advance its political agendas and to provoke tensions with Western governments. Last year, the United States unfroze $6 billion of Iran's blocked funds in exchange for the release of five hostages.

It is believed that Swedes and dual nationals have come under fire since 2022 as a result of the life-sentence handed to former Iranian jailor, Hamid Nouri, imprisoned in Sweden for his role in the purge of dissidents in 1988. Nouri, 62, received the life sentence from a Swedish district court in July 2022 for "grave breaches of international humanitarian law and murder."

After months of legal battles, an appeals court upheld the verdict in December 2023, leading Nouri to seek recourse with the Supreme Court, but the appeal was rejected.