Dissident Expresses Joy Amid Mourning for President Raisi

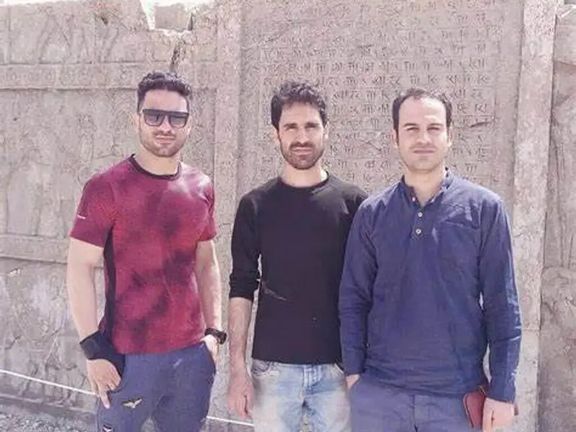

Following Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi's death in a helicopter crash, dissident Saeed Afkari, brother of the executed wrestler Navid Afkari, has publicly shared his joy.

Following Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi's death in a helicopter crash, dissident Saeed Afkari, brother of the executed wrestler Navid Afkari, has publicly shared his joy.

In a message on X, Saeed remarked, "I haven't seen my mother this happy in years." The sentiment reflects the scars left by Raisi's tenure as head of the judiciary, a period characterized by repression and injustice, particularly for families like the Afkaris who suffered directly under his rule.

Navid Afkari was executed on September 12, 2020, after enduring a controversial trial marred by inconsistencies and accusations of torture that occurred during Raisi's tenure.

His execution, amid international condemnation, became a symbol of the regime's oppressive tactics against dissent and its punitive measures against those who dare to challenge its authority.

The torment endured by Navid's family continued as Saeed recounted an incident involving another brother, Vahid. He described how, after Navid’s execution, representatives from Raisi's office coerced Vahid with a life-threatening ultimatum in the shadows of Adelabad Prison in Shiraz, underscoring the impact of Raisi’s policies on countless Iranian lives.

As news of Raisi’s death spread, reactions within Iran were divided, with the majority expressing their jubilation on social media—a contrast to the official mourning period declared by the Supreme Leader. The celebrations reflect a pent-up resentment and opposition toward a regime viewed as suppressive and economically disastrous, highlighting the deep divisions within Iranian society.

The comment by Afkari comes amid an escalating use of the death penalty in Iran, following the unprecedented nationwide protests in 2022. An Amnesty International report released last month, titled "Don't Let Them Kill Us," highlighted an unprecedented surge in executions in Iran in 2023. The report noted that at least 853 individuals were executed, with a significant portion of those executed being minorities, including Kurds.

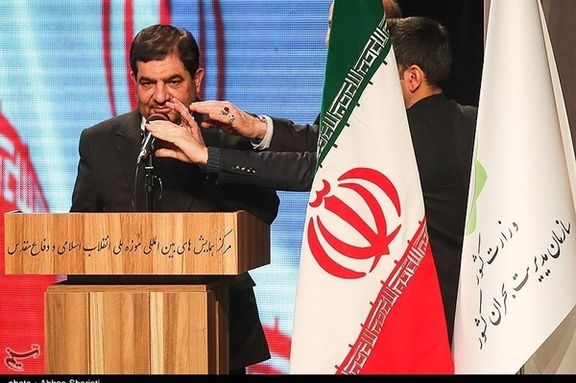

In the wake of the helicopter crash that killed President Ebrahim Raisi, Iran’s Supreme Leader appointed Vice President Mohammad Mokhber as acting president.

“Mr. Mokhber will manage the executive power in line with Article 131 of the Constitution and will coordinate with the heads of legislative and judicial branches to elect a new president within fifty days,” stated Ali Khamenei in a message of condolence. The swift transition underlines the regime's intent to maintain a firm grip on power amidst potential instability.

At 68, Mokhber, who has historically maintained a low profile, is stepping into the limelight under controversial circumstances. His tenure as the head of the Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order (EIKO), and former chairman of the board at Sina Bank, has been marked by ambitions overshadowed by inefficiency and opacity, particularly noted during Iran's struggle to produce a COVID-19 vaccine. Promises of widespread vaccine availability were unfulfilled, raising questions about the allocation of resources and government accountability.

EIKO is an extensive tax-exempt, "charitable" business conglomerate controlled by Khamenei's office, which has its tentacles on a range of sectors in Iran's economy.

Despite the controversies, Mokhber's academic credentials include a doctorate in international law and he has been a member of Iran’s Expediency Council since 2022. His past inclusion and subsequent removal from the European Union's sanctions list for alleged involvement in nuclear or ballistic missile activities adds a layer of international scrutiny to his new role as acting president.

Amidst the leadership upheaval, Ali Bahadori Jahromi, the government spokesman, revealed another significant appointment. Ali Bagheri Kani, previously a political deputy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a former Deputy Secretary of Iran's Supreme National Security Council, has been named head of the government's Foreign Relations Committee.

Kani, known for his role in the September 2023 prisoner release deal with the United States, represents a continuity of Iran's hardline stance in its international negotiations.

The death of former foreign minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian was an opportunity for Mr. Khamenei to appoint a more seasoned and "moderate" figure to try to find some common ground with the United States over its controversial nuclear program and regional issues.

As Iran observes five days of national mourning declared by Khamenei, the recent events not only cast a shadow over Iran's internal governance but also signal potential shifts in its foreign policy approach under new leadership fraught with challenges and skepticism.

Mohammad Javad Zarif, former Foreign Minister of Iran, blamed American sanctions on aviation parts for the crash of a chopper carrying President Ebrahim Raisi.

In an interview with state TV, he said the sanctions compromise Iran's access to modern aviation facilities, thus implicating the US in the Sunday chopper crash in northwestern Iran killing Ebrahim Raisi and his entourage including Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian.

"One of the culprits behind yesterday’s tragedy is the United States, because of its sanctions that bar Iran from procuring essential aviation parts," Zarif asserted during the interview.

His statement comes amid the ongoing geopolitical tension where Iran has increasingly aligned itself with Russia and China, raising questions about its continued reliance on outdated American helicopters like the Bell 212.

The Bell 212, a civilian adaptation of the Vietnam War-era UH-1N "Twin Huey," crashed in heavy fog while traversing mountainous terrain. Developed in the late 1960s for the Canadian military and introduced in 1971, this model was designed to offer enhanced carrying capacity with its dual turboshaft engines.

However, in spite of sanctions, Iran continues to manufacture and supply its own armed forces and proxies around the region, in addition to Russia, with state of the art missiles and drones. Armed groups like Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen and Iran’s own Quds Forces boast long range high-tech weaponry.

Questions are arising regarding who would immediately succeed Iran's President Ebrahim Raisi who was killed in a helicopter crash on Sunday.

According to Article 131 of Iran's constitution, in the event of the death or incapacitation of the president, specific procedures are set in motion to ensure interim continuity of leadership of the current administration until a new election is held.

As per the constitutional provision, if the president is unable to fulfill their duties, the first vice president assumes the role of president. Currently, Mohammad Mokhber holds the position of first vice president in Iran.

However, all constitutional provisions legally and in practice hinge on the approval of the Supreme Leader, who can determine if Mokhber can simply assume the duties of President by himself, or a council should be appointed, which would include the first vice president.

Theoretically, Ali Khamenei can also decide that having just one year left to the next presidential elections, perhaps no quick election is needed and either Mokhber or a council can finish Raisi's four-year term and hold elections on schedule in June 2025.

Mokhber, a close confidant of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, holds a prominent position in Iran's economic landscape as the former leader of the Execution of Imam Khomeini's Order (EIKO).

This conglomerate wields significant influence across various sectors of the Iranian economy, including energy, telecommunications, and financial services, with its operations overseen by the Office of the Supreme Leader of Iran.

As first vice president, Mokhber was also Raisi's point man on economic matters, and shares the blame for chaos in the past 33 months, as the Iranian currency lost 50% of its value. He also stands accused of corruption in the labyrinth of rumors and public opinion, shaped by tidbits of leaks within a controlled media environment.

Article 131, however, outlines the formation of a Council tasked with arranging for a new presidential election within a maximum period of 50 days.

This Council comprises the speaker of parliament, the chief justice, and the first deputy of the President.

The Council's responsibility is to ensure a smooth transition of power and the continuation of governance during this interim period.

In 2021, the US Treasury Department imposed sanctions on Mokhber and EIKO, citing their involvement in human rights violations and the suppression of dissent within Iran.

"EIKO has systematically violated the rights of dissidents by confiscating land and property from opponents of the regime, including political opponents, religious minorities, and exiled Iranians, while, according to its leader Mohammad Mokhber, being tasked by the Supreme Leader to implement a 'resistance economy,'" emphasized the US Treasury in a statement issued in January 2021.

Mokhber's continued prominence within Iran's economic and political spheres and current appointment as first vice-president reflects his loyalty to the Supreme Leader's agenda.

This possibly solidifies his position as a useful figure in Iran's political landscape, potentially positioning him as the next interim Iranian President depending on Supreme Leader Khamenei's decision.

The news of Raisi’s helicopter crash and death has caused speculation about the question of presidential succession and its implications for the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Even before it became clear that President Ebrahim Raisi was killed in a helicopter crash, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, had already assured the public that they should have no fear of any disruptions in the administration of the state.

To those unacquainted with the intrigues and intricacies of the Iranian political system, such debates may come across as illustrious of a vibrant political system where rival factions vie for power. The plentiful memes and jokes about Raisi’s death by many Iranians inside and outside Iranian is most revealing of the dire legitimacy crisis that has afflicted the regime.

Per articles, 60, 113, and 114-142 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran (amended in 1989), the Iranian president technically holds “the second most powerful” office after the Supreme Leader. The president also chairs the State’s National Security Council (176) and is an ex-officio member of the Expediency (Exigency) Council (article 177).

However, the importance of the office of the president should not be exaggerated. As detailed in a seminal survey of the Iranian presidency (The Quest for Authority in Iran: A History of The Presidency from Revolution to Rouhani) by St Andrews University’s Siavush Ranjbar-Daemi, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s presidents have traditionally and constitutionally served at the pleasure of the Supreme Leader and that of Parliament (the Majles), which itself has historically deferred to “the Sultanistic Edicts” (Ahkam-i Sultani) of the Supreme Leader.

The undisputed paramount powers of the state reside in the office of the Supreme Leader, as detailed under article 108. The Supreme Leader enjoys plenipotentiary powers, both spiritual and temporal, over all branches of government (the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary), that are substantially comparable to those of the popes of Rome and Muslim Caliphs of the Middle Ages. Indeed, Supreme Leader Khamenei has ensured that his all too powerful station progressively eclipsed the office of the president and reduced it to that of chief administrator of the state.

Yet, what set Raisi apart from his predecessors, including Khamenei, who himself held the office of the president from 1981 until the death of Khomeini in 1989, is that he epitomized the ideal “executive servant” to the Supreme Leader. His political profile and stature set him apart from all his predecessors.

Since he came Supreme Leader in 1989, Khamenei oversaw the constitutional amendments that eliminated the office of the prime minister, turned the president into a chief executive mandarin, and enshrined “the preponderant” powers of the Supreme Leader into the letter of the constitution. From 1989 to 2021, all presidents of the Islamic Republic of various reformist, moderate, and ultraconservative factions (Hashemi Rafsanjani, Khatami, Ahmadinejad, and Rouhani) squabbled, openly or privately, with Khamenei, and sought to assert their office as “directly elected officials”, but to no avail.

Raisi was an alumni of the faith-based Shia secondary school: the Haqqani School. He along with many of his classmates became revolutionary judges, members of the assembly of experts (responsible for the appointment and dismissal of the supreme leader), appointed representatives of the supreme leader in the praetorian IRGC and the security-intelligence apparatus of the Islamic Republic over the past forty years. They are a most zealous cohort of revolutionary clerics with unequivocal allegiance to the supreme leader. Raisi’s presidency afforded Khamenei the trophy subservient servant he had always wished for.

He rose through the ranks in the Judiciary from a town prosecutor to a provincial prosecutor. In 1988. Raisi presided over the summary secret retrials of thousands of political prisoners who were already imprisoned in the dungeons of the Islamic Republic. In collaboration with zealous prosecutors like Hamid Nouri, Raisi was the hanging judge who sent thousands of political prisoners to the gallows.

Raisi’s curriculum vitae was one of a careerist revolutionary cleric. After Khomeini’s death, Raisi became the Chief Prosecutor for Tehran. Khamenei saw in Raisi a protégé whom he could reward for his loyalty, and thus appointed him head of the State General Inspectorate in 1994. Between 2004 to 2014, Raisi served as the Deputy of the Chief Justice of the State (the Judiciary Chief’s deputy). In 2014-2015, he served as the State’s Attorney General. Between 2015 and 2019, Raisi served as the Chief Trustee of Astan-e Quds, the wealthiest multibillion dollar, religious trust in Iran.

In 2016, Raisi was elected as a member of the Assembly of Experts, and since 2023 he has been the deputy speaker of the Experts Assembly. In 2019, Khamenei appointed Raisi as Judiciary Chief. He proved his loyalty to Khamenei by orchestrating “anti-corruption” trials of former high-ranking judiciary officials, and even though secondary and tertiary officials were prosecuted, the true target of the trials were the powerful Larijani brothers, who had at some point held the Speakership of the parliament as well as the office of the Judiciary Chief.

Finally, in 2021, Raisi was elected president with the helping hand of Khamenei’s appointed Guardian Council. The Guardian Council disqualified many “otherwise qualified” candidates from running, paving the way for Raisi to become president in a low-turnout election which was boycotted by most Iranians.

In view of Raisi’s membership of the Haqqani revolutionary clerics’ circle, and his overtures to the IRGC top brass at the time he was at the helm of the judiciary, his election to presidency in 2021 was an auspicious confirmation to many that he indeed was Khamenei’s heir apparent. Conversely, and against the backdrop of some clerical speculations and objections, some have argued that Khamenei’s son, Mojtaba, is his heir apparent. In a regime like that of Iran’s, a supreme leader’s legitimacy largely hinges on the power of the military and the security and intelligence apparatus as well as the ruling ideological elite.

Currently, the IRGC (praetorian guard of the regime) controls much of the country’s economic infrastructure as well as large swathes of the private sector and has a strong grip over the Iranian armed proxies in the region. Mojtaba is revered by the security and intelligence establishment, the IRGC top brass, and many deputies in the Assembly of Experts, and has been chiefly in charge of running the supremely powerful “Office of the Supreme Leader” for his father for almost two decades. Such debates about succession now that Raisi is dead are moot. As to the fate of the presidency, article 131 of the constitution stipulates that:

In case of death, dismissal, resignation, absence, or illness lasting longer than two months of the President, or when his term in office has ended and a new president has not been elected due to some impediments, or similar other circumstances, his first deputy shall assume, with the approval of the Leader, the powers, and functions of the President. The Council, consisting of the Speaker of the Islamic Consultative Assembly, head of the judicial power, and the first deputy of the President, is obliged to arrange for a new President to be elected within a maximum period of fifty days. In case of death of the first deputy to the President, or other matters which prevent him to perform his duties, or when the President does not have a first deputy, the Leader shall appoint another person in his place.

What makes the present situation most dire is that if Khamenei dies before a new president has been elected, the country may potentially plunge into nationwide unrest. If the 2022-2023 nationwide “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising is any guide, and in view of Iran’s ongoing decrepit economic situation that has pushed over sixty percent of Iranians into poverty, the regime already grapples with an endemic crisis of legitimacy. Thus, it is Khamenei’s demise that can potentially trigger a manifold crisis.

In sum, the prime directive, and the categorical imperative, that guides the members of the Assembly of Experts, and the entire ruling echelon of the Islamic Republic is: “the Survival of the Regime.” Under a scenario that the regime is at once devoid of both the supreme leader and the president, the Assembly of Experts may indeed swiftly elect Seyyed Mojtaba Khamenei who enjoys the unquestionable loyalty of the IRGC top brass and the security and intelligence establishment. If so, Seyyed Mojtaba Khamenei’s leadership shall usher in an era of theocratic dynasty in the Islamic Republic following the same model of early medieval Shia imamate dynastic succession.

Ebrahim Raisi, effectively appointed by Iran’s Supreme Leader as president in June 2021, was killed in a helicopter crash on May 19, exactly 63 years and five months after his birth in northeastern Iran.

This is the story of a young member of the Death Committee that ordered the execution of around 5,000 political prisoners serving their prison terms in 1988. He loyally served the clerical regime for 45 years and finally was elected President after Ali Khamenei’s men barred most serious rivals from running as candidates.

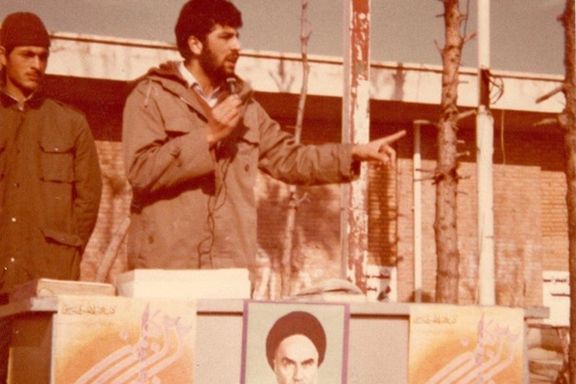

"The greatest crime in the Islamic Republic since the beginning of the revolution was committed by you. In the future, you will be remembered among the criminals of history." These were the words that Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, the dismissed deputy of the Islamic Republic’s first Supreme Leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, said to a group of five that later became known as the Death Committee on August 15, 1988. One of them was the 28-year-old deputy prosecutor of Tehran, Ebrahim Raisi. The eighth president of the Islamic Republic was killed in an aviation accident taking many secrets to the grave with him. Ebrahim Raisi was born in December 1959 in Mashhad and completed his primary education at Javadiyeh Elementary School in this city, after which he enrolled in a seminary and never received a standard education.

He entered the seminary in Qom in 1975 and began his clerical studies at Boroujerdi School, supervised by Morteza Pasandideh, the elder brother of Ruhollah Khomeini. In fact, when the Islamic Republic was established in 1979, Raisi was 19 years old and four years into his clerical studies. At 20 years old, with only five years of clerical study, he was appointed as a deputy prosecutor in Karaj. Islamic law needed clerical prosecutors and judges whose main education was knowing the Sharia.

In 1982, at the age of 22, he became the prosecutor of Hamedan and married Jamileh Alamolhoda, daughter of Ahmad Alamolhoda, the current Friday prayer Imam of Mashhad. At 25, in 1984, Raisi was appointed deputy head of the Revolutionary Court and, in 1988, as deputy prosecutor of Tehran, he joined the Death Committee, which directed the execution of thousands between August and September 1988.

After Khomeini's death, from 1989 to 1993, he served as Tehran's first prosecutor under Ali Khamenei's leadership. From 1993 to 2003, he was the head of the General Inspection Organization. From 2003 to 2013, under the judiciary chiefs Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi and Sadeq Larijani, he served as the first deputy head of the judiciary. For a short period from 2014 to 2015, he was the Attorney General of Iran. From 2015 to 2019, Ali Khamenei appointed him as the custodian of Astan Quds Razavi, an important and wealthy Shiite shrine. During this period, rumors about his potential succession to Khamenei intensified, fueled by images of his meetings with IRGC commanders and a special envoy from Putin.

Raisi attempted to change his appearance, wearing a cloak instead of his traditional robe, and engaged with people in Khorasan, hoping to win the 2017 presidential election. However, he was defeated by Hassan Rouhani, receiving about 16 million votes compared to Rouhani's 24 million. Following Sadeq Larijani's controversial departure from the judiciary, Raisi, after failing to secure the presidency, was appointed head of the judiciary by Ali Khamenei.

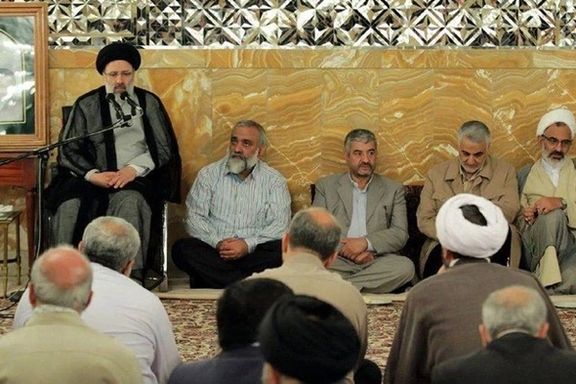

Images of senior IRGC commanders meeting with Ebrahim Raisi at Astan Quds fueled speculation about his potential succession after Khamenei. During his tenure, he conducted high-profile trials, such as that of Akbar Tabari, the former deputy of Sadeq Larijani, building an anti-corruption image while sidelining Larijani, who was considered a potential successor to Khamenei. During this time, he held another significant position. From June 2012 to September 2021, he was the prosecutor of the Special Clerical Court, an institution established by Ruhollah Khomeini and operating outside the judiciary, directly overseen by the Supreme Leader, dealing with clerical infringements.

In 2021, Raisi entered the presidential race again, winning one of the lowest-turnout elections in the history of the Islamic Republic. His presidency was marked by severe economic recession and inflation, as sanctions imposed by former US President Donald Trump and worsening mismanagement and corruption ravaged the economy.

His weak and often blundering speeches cast a shadow over his aspirations for succession. Three years into his presidency, economic indicators reached unprecedented lows.

The most intense wave of protests, strikes, and the revolutionary uprising of 2022 occurred during his tenure.

On May 19, 2024, at the age of 63, Ebrahim Raisi died without realizing his ultimate dream of becoming the Supreme Leader.

He will be remembered by Iranians for his many blunders that revealed his lack of education, and his role in the Death Committee -- overseeing the deaths of thousands of innocent lives.